Lean UX – Getting Out Of The Deliverables Business

User experience design for the Web (and its siblings, interaction design, UI design, et al) has traditionally been a deliverables-based practice. Wireframes, site maps, flow diagrams, content inventories, taxonomies, mockups and the ever-sacred specifications document (aka “The Spec”) helped define the practice in its infancy. These deliverables crystallized the value that the UX discipline brought to an organization.

Over time, though, this deliverables-heavy process has put UX designers in the deliverables business — measured and compensated for the depth and breadth of their deliverables instead of the quality and success of the experiences they design. Designers have become documentation subject matter experts, known for the quality of the documents they create instead of the end-state experiences being designed and developed.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- The Lean UX Manifesto: Principle-Driven Design

- Effectively Planning UX Design Projects

- Incorporating More Quiet Into The UX Design Process

- A Collaborative Lean UX Research Tool

When combined with serial waterfall development methodologies, these design deliverables end up consuming an enormous amount of time and creating a tremendous amount of waste. Waste is defined as anything that is ultimately not used in the development of the working product.

As organizations struggle to stay nimble in the face of an ever-changing marketplace that is disrupted constantly by incumbents as well as start-ups, getting to market fast becomes top priority. Engaging in long drawn-out design cycles risks paralysis by internal indecision as well as missed windows of market opportunity. In other words, by the time the company decides internally how the product should be designed, the needs of the marketplace have changed.

Waterfall software development looks something like this:

Define → Design → Develop → Test → Deploy

The design phase typically breaks down like this:

Wait for requirements definition to take place and get approved → Consume requirements documents → Develop high-level site maps and workflows → Gain consensus and approval → Develop screen-level wireframes for each section of the experience → Present to stakeholders and gain consensus and approval → Create visual designs for each wireframe → Present to stakeholders and gain approval (after repeated cycles of review) → Write The Spec, detailing every pixel and interaction → Usability test for future improvements → Hand off to development for review, approval and start of implementation

This phase can take anywhere from one to six months depending on the scope of the project, leaving many wasted hours and much designer frustration in its wake.

Enter Lean UX.

Lean UX

Inspired by Lean and Agile development theories, Lean UX is the practice of bringing the true nature of our work to light faster, with less emphasis on deliverables and greater focus on the actual experience being designed.

Traditional documents are discarded or, at the very least, stripped down to their bare components, providing the minimum amount of information necessary to get started on implementation. Long detailed design cycles are eschewed in favor of very short, iterative, low-fidelity cycles, with feedback coming from all members of the implementation team early and often. Collaboration with the entire team becomes critical to the success of the product.

Interestingly and not surprisingly, one of the immediate casualties of Lean UX is the stereotypical solitary designer, working silently in a corner for a period of time, inviting only occasional peeks at their work before it’s “done.” This mindset is also the biggest obstacle to wider adoption of this practice.

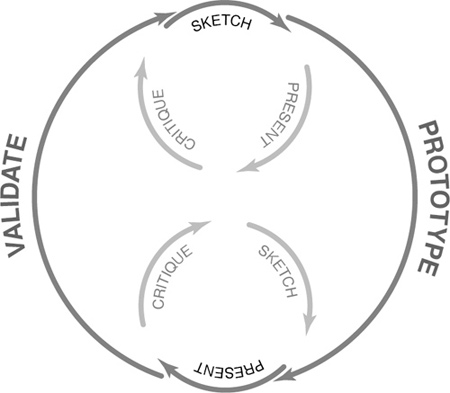

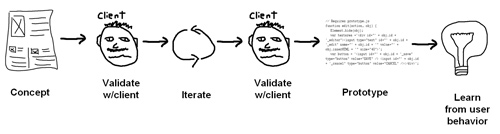

Let’s take a look at the Lean UX process:

Looks familiar? It should if you’re familiar with Agile or its derivatives. Lightweight concepting kicks off the process. This can be done on a whiteboard, a napkin or a quick wireframe. The goal is to get the core components of the idea or workflow visualized quickly and in front of your team.

The team begins to provide their insights on the direction of the design as well as its feasibility. Changes are then made to the original idea, or perhaps it’s scrapped entirely and a new idea proposed. The initial investment in sketching is so minimal that there is no significant cost to completely rethinking the direction. Once a direction is agreed upon internally, a rough prototype helps to validate the idea with customers. That learning helps to refine the idea, and the cycle repeats.

What’s most important to recognize here is that Lean UX is focused strictly on the design phase of the software development process. Whatever your organization’s chosen methodology (waterfall, Agile, etc.), these concepts can be applied to your design tasks.

Isn’t This Just Design-By-Committee?

Lean UX encourages you, the designer, to show your work early and often to the team, collect their insights and build that into the next iteration of the design. To many folks, this sounds like the dreaded “design by committee” approach, which has killed many designs in years past.

In fact, the designer is still driving the design by aggregating all of that feedback, assessing what works best for the business and the user, and iterating the design forward. By providing insight into the design work to your teammates sooner rather than further down the design road, you accomplish the following:

- Ensure that you’re aligned with the broader team and the business vision;

- Give developers a sneak peek at the direction of the application (speeding up development and surfacing challenges earlier);

- Further flesh out your thinking, since verbalizing your concepts to others forces you to focus on areas that you didn’t think of when you were pushing the pixels.

The trick is to stay lean: keep the deliverables light and editable. Eliminate waste by not spending hours getting the pixels exactly right and the annotations perfect. Got an idea for a flow? Throw it up on the whiteboard, and grab the product owner or project leader to tell them about it. Ready to design? Rough out the first page of the flow in your sketchpad. How does it feel? Is the flow already evident? Post it in a visible place at the office and invite passers-by to comment on it.

As you iterate, suggestions and feedback from various team members will inevitably start to manifest themselves in the experience. The team members who suggested these ideas will begin to feel a sense of ownership in the design and notice it in others. It has now become something they had a hand in creating. This sense of ownership will equip the designer with new allies to defend the work when it comes under criticism from external forces. The team ultimately becomes more invested in the success of the experience.

Lean UX Is Not Lazy UX

It may seem at first that this is a lazy approach to UX, that the goal is simply to do less work. On the contrary, you’re actually using all of the tools in your UX toolkit. Sketching, presenting, critiquing, researching, testing, prototyping, even wireframing — these all get a solid workout in each cycle of the process. The trick is to use these tools when appropriate and, more importantly, to use them at the depth appropriate for the immediate problem you’re trying to solve for the business.

Designers Need to Feel in Control of Their Work

“But I’m giving up control of my design!” is one of the most often-heard complaints from designers who try out Lean UX. Their concern is that by collecting feedback from non-designers, they will be less valuable to the team and be relegated to the role of menial pixel-pusher.

By staying lean, however, the frequent collection of team-wide feedback actually minimizes the time spent heading down the wrong path. The designer continues to drive the design, but the guardrails (i.e. constraints) become more visible with each iteration and review. Basically, if you spend three months perfecting a design only to find out after launch that it fails to meet customers’ needs, then you’ve just wasted three months of your life, not to mention your team’s.

Lean UX also speeds up development time. By giving the team early insight into the design’s direction, it can begin to lay the groundwork for that experience. This foundational coding phase helps to expose feasibility challenges in the proposed solution. The time, material and resources available then help to prioritize the product’s elements, separating the parts that get built from those that get pushed out or reduced in scope. All of this affects where the designer focuses their energy, thus minimizing waste.

Prototyping: The Fastest Way Between You and Your Customers

Lean UX is where prototyping shines. As with the initial sketches, focusing the prototype on critical components of the experience is essential. Pick the core user flow (or two), and prototype only those screens. The fidelity of the prototype ultimately doesn’t matter, so create it the way you know best. Once created, it will be immediately testable by any and all users.

Successful lean prototypes have been created with code, with design software such as Adobe Fireworks and even with PowerPoint. At times, your client (internal or external) will demand a level of fidelity that helps them better visualize the experience. Work with the tool that is most comfortable and fastest for you and that delivers just enough fidelity for the client.

Next, get that prototype in front of everyone who matters internally, and validate whether you’re meeting the needs of the business.

Most importantly, get the prototype in front of customers. Bring them in regularly to test the workflows, ideally once a week. You don’t need to test with many customers. Jakob Nielsen found out that after five participants, the odds of finding new roadblocks in the experience were low. If you test regularly, you can cut the number of participants per week to three. This will also cut costs.

Collect feedback. Figure out what worked and what didn’t. Tweak the prototype. Hell, gut it if you have to: that’s the beauty of Lean UX. The investment you’ve put in at each phase is so minimal that rethinking, reconfiguring or redesigning isn’t crushing in workload or ego-bruising.

Once validated, demo your updated prototype to the team. Explain the flows, the user motivations and why you designed it the way you did. The prototype has now become your documentation. It is “The Spec.” Very little (if anything) more is needed. Regardless, you’re there to answer any questions that come up. The strength of Lean UX here is that, with the design validated, the designer is now freed to move on to the next core component of the experience, instead of spending six weeks creating a design-requirements document and pixel-perfect specs.

Prototyping puts the power of validating the design’s direction much more quickly in the hands of the ultimate decider: your customers. They are the ones with whom the design will speak for itself, and in the environment where it will ultimately have to succeed.

Maintaining a Holistic Vision

“But what about my vision? By chopping the design up and delivering it piecemeal to the team and, ultimately, customers, I’m compromising on my vision of the product and putting out a sub-standard experience!”

UX designers have traditionally worn many hats. You now have another to add to the hall tree: keeper of the vision. In this new role, your responsibility is to keep an eye on the big picture. Lean UX forces you to think of the experience in prioritized chunks. Ultimately, those chunks all have to roll up into one cohesive product. That cohesive product is your vision. Even as the design shifts and morphs through iterations and customer feedback, you are always designing towards that greater goal. “Increasing time on site for returning customers” could be a vision. “Deliver content faster and in a more contextual manner” could be another. Regardless of how the design shifts, these goals drive your work.

It won’t be easy. In the past, those hard-won, comprehensive, approved deliverables authorized you to design in a specific direction. With Lean UX, the iterative cycle and the frequent varying opinions will inevitably create conflicts with your vision. This is where you push back. Use the stated vision to help sort out conflicting feedback and focus your efforts on the end goal.

Deliverables For Maintenance Don’t Make Sense Anymore

Documentation has long served as a way for organizations to maintain their software. It becomes a reference tool to understand the decisions of the past, which inform the decisions of the present. While this may make sense for complex business rules, it doesn’t make sense for design. The final product is the documentation. It is the experience. Thick deliverables created simply for future reference regarding the user experience become obsolete almost as soon as they are completed. When a question arises about how something should behave in the UX, going through that workflow in the product to see what happens is easy enough. The old kind of documentation is waste and draws effort away from solving current design problems.

How Does Content Strategy and Planning Fit In?

Websites and applications that are focused on heavy content delivery (as opposed to task- or function-based websites) will need some up-front planning and documentation. Getting right down to the level of the page and article may not be necessary, but getting enough of an idea of the type of content that will be delivered and a sense of its hierarchy is essential to getting to that first sketch and prototype. Once the team grasps the scope and type of content needed for the experience, work can begin as the experience is refined.

Can It Be Done At My Organization?

At the risk of oversimplifying, let’s look at two types of organizations: the internal software/design shop and the interactive agency.

For internal software/design organizations, the transition to Lean UX is well within reach. You are in the problem-solving business, and you don’t solve problems with design documentation. You solve them with elegant, efficient and sophisticated software. Working in these new attributes should ultimately be an easy sell internally because you are advocating for more collaboration, more conversation and earlier delivery to customers. Yes, the culture will have to shift — shipping what amounts to the minimum desirable product can be a tough pill to swallow for those used to big-bang releases. However, the ability to make quicker decisions along the way, informed by regular customer feedback, should ultimately trump these concerns.

Interactive agencies have it a bit tougher because they are in the deliverables business. They get paid for their documentation and spend a lot of time creating it. A specialist creates each document, and they charge for that time. Reducing those efforts means reducing revenue.

Lean UX proposes that the shortfall in up-front revenue generated by deliverables can easily be made up, and then some, by delivering higher-quality work, faster, to the client. The process has to be modified slightly, though:

The core difference with the agency’s process is the regular and frequent involvement of the client. Set up twice- or thrice-weekly 30-minute reviews with them. Set the expectation that you’ll be showing rough, directional work and that you’ll want their feedback. Each time you review a directional sketch with your client, they’ll notice the evolution and progress. Their feedback will work its way in and, like an internal stakeholder, they’ll gain that sense of ownership.

By involving the client in the process, by iterating the design quickly and by testing the iterations with real customers, you will reach an optimal solution in less time than before.

In agency-land, less time typically means less revenue, which could potentially be the death knell for Lean UX. But while the output took less billable time to create, it will likely be more effective and will bring the customer back to your shop more frequently than in the past. In addition, you’ve made the client part of the process. This is empowering, and clients like that feeling.

This is not an easy change because agency culture has been the same for many decades. Only the boldest agencies will take this on. But those that do will find greater success from it and will quickly be imitated. These ideas are worth piloting on an internal project; perhaps the redesign of the agency’s website. Prove that they work, and then branch out to actual clients.

I’m a Consultant/Freelancer. Does This Make Sense for Me?

Consultants are, in essence, an agency of one. It stands to reason that the agency process could work in this situation as well. Constant feedback and iteration with the client will engender the same feelings of trust and co-ownership. The challenge for the consultant/freelancer is the amount of time they can dedicate to each client. Assuming they can handle multiple projects or clients simultaneously, providing the level of attention and communication necessary to maintain a true Lean UX process becomes difficult. In this case, falling back on a slightly deeper level of documentation makes sense to keep concurrent projects moving forward.

It’s worth mentioning that one big challenge for Lean UX to be successful in any of these settings is the use of offshore development vendors. One of the fundamental principles needed for Lean UX to succeed is collaboration — ideally in real time and place it can even work via Skype or other virtual meeting technology. When a vendor has minimal contact with your design group and requires a certain level of documentation in order to produce work, Lean UX may not work in its entirety.

Lean UX is being actively used by a growing number of organizations. The way TheLadders has implemented it in a recent effort is an example of keeping deliverables light, fostering greater collaboration and achieving goals successfully.

Conclusion

Lean UX is an evolution, not a revolution. UX designers need to evolve and stay relevant as the practice evolves. Lean UX gets designers out of the deliverables business and back into the experience design business. This is where we excel and do our best work. Let’s become experts at delivering great results through these experiences and forgo the hefty spec documents. It won’t be an easy road. Culture and tradition will push back, yet the ultimate return on this investment will be more rewarding work and more successful businesses.

How To Measure UX and Design Impact, 8h video + UX training

How To Measure UX and Design Impact, 8h video + UX training Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why! JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

Register For Free

Register For Free Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial