Lightening Your Responsive Website Design With RESS

*Editor’s Note: This article features just one of the many solutions for creating high-performance mobile websites. We suggest that you review different approaches such as Building A Responsive Web App, Improving Mobile Support and Making Your Websites Faster before choosing a particular solution.*

This article explains how to use RESS (responsive design with server-side components) to make significant performance and reach improvements to a website for both mobile and desktop devices alike. This technique requires just a few lines of code, some simple configuration and no ongoing maintenance.

Your website will change from one that works on desktops, tablets and smartphones to one that works on almost anything anywhere and loads faster in all cases. It’s hard to over-emphasize the importance of this, but if you need a good case study, read about what happened to YouTube when Google lightened its pages (spoiler: entire new territories opened up to it).

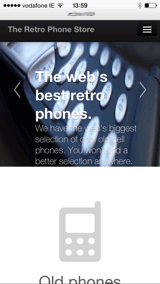

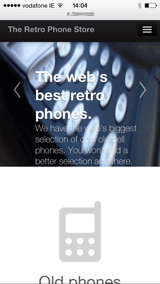

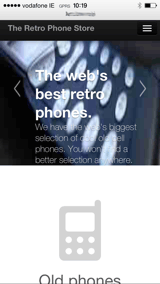

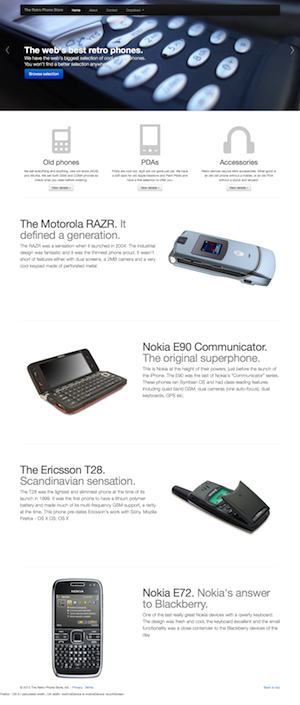

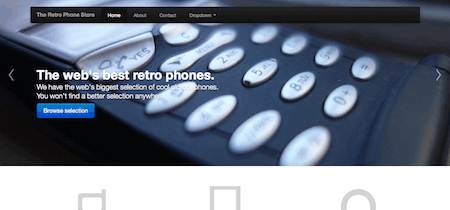

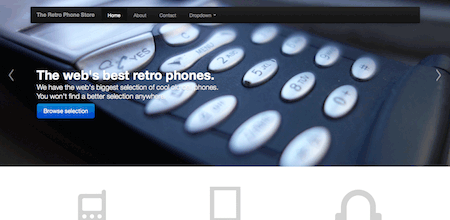

The following three screenshots show a sample website with increasing levels of RESS optimization being applied to it and the resulting overall page sizes:

Original: 1,027 KB (large preview)

Partial optimization: 253 KB (large preview)

Full optimization: 153 KB (large preview)

The discerning reader will note that the screenshots all look the same, and that’s the whole point: The optimization procedure we’ll be applying ensures that the optics of the website remain intact, while improving the user experience significantly due to the smaller page size. In fact, the screenshots are not exactly the same (click to view them at native size), but the slight differences in the quality of the images tend to go unnoticed on phone screens.

Language issues aside, making a website truly accessible worldwide usually comes with two problems:

- Diversity of devices

Remember what the first two W’s in WWW stand for? A truly global website should work on any devices that your customers use, with varying connectivity standards, world-wide. - Constrained connectivity

Many places are not well connected to the Internet, whether in terms of capacity, data plans, etc. This problem affects people living in modern well-connected cities as much as people in less developed rural areas.

This article will help your website break through this glass ceiling (or floor) and enable everyone everywhere to reach your content with equal ease. Note that we’ll be using open-source software in conjunction with a device-detection library to achieve this goal; there are many device-detection solutions out there (such as WURFL, OpenDDR and DeviceAtlas — I was involved in developing the latter one).

We’ll demonstrate three levels of optimization, each building on the previous one, but each of which can be implemented separately, too. These optimizations will take on the following:

- Reduce image payload (the biggest effect),

- Reduce JavaScript and CSS payload,

- Further optimize based on bandwidth detection.

Before we begin, let’s confirm why this process is necessary.

Background On Responsive Web Design And RESS

Responsive Web design is fast becoming the preferred method for making a website mobile-friendly, and with good reason. For many websites, it achieves a reasonable balance between mobile-friendliness and ease of implementation.

But design isn’t just about appearance, and the main problem that we all are struggling with in Responsive Web design is that by “default” (when using the simplest way to display and hide containers with display: none;) all devices are sent the same payload. It means that devices with low-resolution screens are sent the same images as those sent to high-resolution devices, even though they can’t show them at their native resolution. This is inefficient at best and market-limiting at worst. The result is a page that works well on high-end well-connected devices with generous data plans.

Many attempts have been made to solve this problem, with varying levels of effectiveness. Probably the most promising approach has been to have the browser determine the most appropriate image version to fetch. The W3C has an ongoing initiative to standardize an approach, but this likely won’t be commonplace in browsers within the next year or so. The candidate solutions — the new <picture> element and new srcset attribute for the <img> element — each has its own issues and benefits. Rather than discuss them here, I suggest reading Jason Grigsby’s “The Real Conflict Behind <picture> and @srcset.” In the meantime, polyfills such as Boris Smus’ srcset-polyfill will mimic some of the proposed attribute’s behavior.

We’ll describe a relatively straightforward approach to minimizing page weight in RWD using a touch of server-side magic. We’ll use device detection on the server to optimize images when they’re requested by the browsers by reducing their dimensions to the optimum size.

Some people use Sencha.io Src (neé TinySRC) and other image-resizing libraries, but doing this yourself is just as easy, and then you’ll have total control over the result. Yes, this does exchange one external dependancy for another, but it also enables you to optimize much more than images. We’ll use PageSpeed for this purpose, an open-source project from Google.

PageSpeed is a Web server module that applies multiple best practices to a website without forcing the developer to change their workflow. These optimizations include combining and minifying JavaScript and CSS files, inlining small resources, removing unused meta data from each file, and re-encoding images to the most efficient format accessible to the user. PageSpeed is available for both Apache and NGINX. We’ll take advantage of a little-used image-resizing feature of PageSpeed.

The resulting weight savings are dramatic and require very little work. If you follow the steps in this article, you should be able to cut down on image weight many times over with three easy steps, only four lines of code and one line of configuration.

This article assumes that you are using the Apache Web server and are comfortable with some light PHP coding, but the techniques will work with NGINX also, and any programming language.

The Website

Our sample website is based on Twitter’s open-source Bootstrap Web framework, to save the world from my design skills. I created a single-page “website” for a fictional mobile phone store. The page is visually rich, with an industry-average breakdown of HTML, images and JavaScript. This page is based on a lightly modified version of Bootstrap’s carousel template. Here is the page in its entirety, as you would see it in a desktop browser:

The website has an approximately industry-average payload that breaks down as follows:

| Component | Size on disk |

|---|---|

| HTML | 12 KB |

| Image | 941 KB (73%) |

| JavaScript (mostly minified) | 159 KB |

| CSS | 170 KB |

| Total | 1,281 KB |

Instructions

Step 1

Install PageSpeed. This is best done by following Google’s instructions. The installation process will usually activate the module for the default website, but you might need to ensure that it works with your virtual hosts, if they’re configured. Basically, you just have to add a line to each one, or get them all to inherit from the default configuration server-wide.

Next, restart your Web server.

Step 2

Get a device detection library set up. In our case, if you are using DeviceAtlas (which we’ll use just as an example here), you’ll need to enter your license key in the DeviceAtlasCloud/Client.php file after you unpack the ZIP file. We then can use DeviceAtlas to determine the optimal size for images.

Step 3

Copy DeviceAtlas’ PHP file to a directory where it is executable by the Web server. In this case, I’ve created a directory in the root of the website, named DeviceAtlasCloud. Enter the following code at the top of your HTML file or website template to set up a couple of variables that we can use throughout the page. If you’re using a different solution, then the syntax will vary but the same properties should be available.

<?php

include 'DeviceAtlasCloud/Client.php'; // instantiate client

$results = DeviceAtlasCloudClient::getDeviceData(); // fetch props

$props = $results['properties']; // store result

// set $width to correct width or "" if unknown

$width = (isset($props['displayWidth'])) ? $props['displayWidth'] :"";

?>

The impact of this fetching of properties should be no more than a few milliseconds if everything is set up correctly as most solutions will cache data.

Step 4

The final step is to give all of your images that might need resizing a width attribute, set to use the $width variable:

<img src="https://www.smashingmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07slide-01.jpg" width="<?php echo $width; ?>" alt="image description" />

Thus, images will now have their width attribute set from the $width variable, which is set automatically to the maximum display width for each device. Then, PageSpeed will notice the width="…" tag for each image and scale it down if necessary, replacing the image source’s attribute with a reference to a resized version of the same thing. There is no need to set the height attribute because PageSpeed automatically retains the aspect ratio. Resized images are cached, so there isn’t really any significant impact on the server. Refer to the PageSpeed configuration notes below for more fine-grained control of this cache.

Add this variable width tag only to images that will need to be resized for each device; that is, don’t add it to images that are already small enough (such as bullets and icons). Manually resizing images that require special attention might also be wise. Also, be aware that the width attribute for each image will need to play nice with any CSS used for image styling. Anyone using a content management system (CMS) might have to use a different technique for this, depending on how much access the CMS gives them to the underlying HTML.

Background images might require a different approach, depending on how they are implemented on the website. Still, PageSpeed will read inline style="…" tags.

Result

With those changes made, it’s time to see how the website looks. To measure the impact of this step, I tested the download speed of our website for different devices and network speeds, using the ever-useful Charles Proxy as well as real devices that I forced into various network configurations to reduce available bandwidth.

Before making the changes, the page’s overall size was 1,027 KB, regardless of device (i.e. a dynamic range of exactly 1.0). The breakdown is as follows:

| Component | Size on disk | Size over network |

|---|---|---|

| HTML | 12 KB | 3 KB |

| Images | 941 KB | 941 KB (73%) |

| JavaScript | 159 KB | 55 KB |

| CSS | 170 KB | 27 KB |

| Total | 1,281 KB | 1,027 KB |

This is the over-the-network size of the page, thanks to gzip compression from Apache. The RWD makes the page look OK on small screens, but it isn’t an efficient use of network resources because the original images are about five times wider (in pixels) than the average phone screen and, hence, impossible to display at full resolution without panning. In fact, the sheer size of the page means that it doesn’t even finish loading on some devices.

After following the above steps, the payload breakdown for an iPhone is this:

| Component | Size over network |

|---|---|

| HTML | 3 KB |

| Images | 177 KB |

| JavaScript | 51 KB |

| CSS | 21 KB |

| Total | 253 KB |

So, the page has dropped to one fourth of its original size, with image sizes accounting for the majority of this reduction. On devices with lower-resolutions screens, further gains are possible; the same page on a Nokia feature phone (Nokia 6230) now has a total image weight of just 89 KB, a large saving compared to the original. Importantly, the before and after websites have no perceptible difference to the user; the image data that was removed cannot easily be seen by the mobile user.

After following the four steps outlined here, the page’s weight now varies between 1,027 KB and about 150 KB. In other words, the page has gone from having a dynamic range factor of exactly 1.0 to a decent 6.8, with the image payload shrinking from 941 KB to just 80 KB. This will have a huge impact on real-world customers:

- Much faster page-loading times lead to better engagement and fewer drop-offs.

- A smaller impact on the user’s data plan leads to more return visits.

- Wider device and network compatibility leads to improved reach.

Here’s the loading-time effect on a Retina iPhone using 3G and 2.5G networks:

| Device and network | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| iPhone 3G | 14s | 6s (2.3× faster) |

| iPhone GPRS | 2m 30s | 35s (4.3× faster) |

The results on Android devices are similar. On lower-end devices with smaller screens, more dramatic improvements are possible because the image-resizing gains are greater.

Going Further, Part 1: JavaScript And CSS

So far, we’ve looked only at the main source of bloat on pages: images. But screen size shouldn’t be the sole factor in our methods — user contexts and constraints demand more of a multi-device publishing strategy because many additional optimizations are to be made. For example, if you know that the requesting device doesn’t support JavaScript or rich CSS, then ditching them might make sense. This is quite straightforward to accomplish.

If we add another line of PHP to the top of our HTML file, we can do a little more.

$highEndDevice = (isset($properties['browserRenderingEngine']) && in_array($properties['browserRenderingEngine'], array('Gecko', 'Trident', 'WebKit', 'Presto')));

We are making the determination of a low-end device based on its rendering engine. This is a crude rule but good enough to demonstrate a point. Based on this variable, we can now selectively include some resources only if they’re beneficial. In this case, if the device appears to be low end, we’ll jettison the CSS and JavaScript, because low-end phones will have problems with both the file size and the rendering of this CSS, and they usually won’t run the JavaScript:

<?php if ($highEndDevice): ?>

<link href="css/bootstrap.css" rel="stylesheet">

<link href="css/bootstrap-responsive.css" rel="stylesheet">

<link href="css/additional.css" rel="stylesheet">

<?php endif; ?>

And now the JavaScript:

<?php if ($highEndDevice): ?>

<!-- Le javascript

================================================== -->

<!-- Placed at the end of the document so the pages load faster -->

<script src="js/jquery.js"></script>

.

.

<?php endif; ?>

This saves a further 72 KB (quite a reduction from 253 KB!) and actually makes the page look better on low-end devices (see the screenshot at the end of this article), in addition to being quicker to render. Now, when viewed on a low-end device, the page’s weight is as follows:

| Component | Size over network |

|---|---|

| HTML | 3 KB |

| Images | 50 KB |

| JavaScript | 0 KB |

| CSS | 0 KB |

| Total | 53 KB |

This means that our simple RWD page has gone from a fixed size of about 1 MB to a highly varying one that goes as low as about 50 KB, or 20 times smaller than the page we started with. Not a bad result for fewer than 10 lines of code. The net result is that our page is now viewable on almost anything, anywhere, from televisions to feature phones — and quickly! You might not be targeting televisions and feature phones, but now they will come to you.

Note: In testing this approach on real devices, HTML5’s doctype tag did not cause problems. The page loaded on pretty much every device I tried.

Going Further, Part 2: Connectivity Detection

Most of the weight savings so far hinge on certain low-end mobile devices not needing full-resolution images, rich styling or JavaScript. This set of techniques is highly effective, but we can do more to cater to our users and extend our reach. Desktop devices sometimes need help, too. Anyone who has used a laptop over airport Wi-Fi or in a poorly connected country knows just how frustrating viewing large pages is.

Connectivity detection comes to the rescue here. The idea is that, if you can detect the connectivity available to the requesting browser, then you can apply similar image-compression techniques dynamically according to the client’s available bandwidth. This can make a huge difference to the browsing experience, at some cost to page fidelity: If we detect a poor connection, then images can be aggressively compressed without reducing their pixel size. The result is a page that loads much faster, with only a slight impact on the experience — the page’s layout and overall appearance will be preserved. Depending on the compression levels, many people won’t even notice.

The W3C is working on making bandwidth information available to the browser, but the Network Information API is still in draft status and so won’t be widely deployed in the near future.

In the meantime, we can use some server-side capabilities. DeviceAtlas incorporates a feature to do exactly this, enabling the developer to make useful decisions about what to send to the client when bandwidth is limited. For this example, we’ll do something simple yet effective: If the bandwidth available to the device is detected to fall below a certain threshold, then we will redirect the browser to a different virtual host. This virtual host will be served by the same Web server and will serve exactly the same page, but it will trigger a different set of options for PageSpeed. In this case, we’ll change the image-compression level from its default to something much lower — say, 20%. At this level, images will still be very recognizable and will fit the page’s layout but will be many times smaller in bytes.

What follows is a simple way to achieve this, explained merely as a quick example of what is possible rather than as a definitive technique. First, add a new virtual host to your server’s configuration, and configure PageSpeed to use different settings for it. Then, restart your Web server. I am using site.com and lo.site.com as my virtual hosts. Note that the DocumentRoot is the same in each case — the exact same HTML is being served for both virtual hosts.

<VirtualHost *:80>

ServerAdmin webmaster@localhost

ServerName site.com

DocumentRoot /var/www/site.com

ModPagespeed on

</VirtualHost>

<VirtualHost *:80>

ServerAdmin webmaster@localhost

ServerName lo.site.com

DocumentRoot /var/www/site.com

ModPagespeed on

ModPagespeedImageRecompressionQuality 20

</VirtualHost>

Next, add the connectivity-checking code to your website’s template. This is what switches the virtual host if connectivity appears to be poor:

require_once 'DeviceAtlasNPC.php'; // check network performance

session_start();

$deviceAtlasNPC = new DeviceAtlasNPC(); // instantiate NPC

$quality = $deviceAtlasNPC->getQuality(); // test network performance

$path = $_SERVER['SCRIPT_NAME'];

switch($quality) {

case DeviceAtlasNPC::HIGH_QUALITY:

if ($_SERVER['HTTP_HOST'] == 'lo.site.com') {

header("Location: https://site.com".$path );

}

break;

case DeviceAtlasNPC::MEDIUM_QUALITY:

if ($_SERVER['HTTP_HOST'] == 'lo.site.com') {

header("Location: https://site.com".$path );

}

break;

case DeviceAtlasNPC::LOW_QUALITY:

if ($_SERVER['HTTP_HOST'] == 'site.com') {

header("Location: https://lo.site.com".$path );

}

break;

default:

}

Yes, the initial redirection to the low-bandwidth website does affect the loading time, but this penalty is far outweighed by the net savings in doing so, particularly for users with constrained bandwidth; high-bandwidth users should be almost unaffected. The cost of this redirection on a slow GPRS connection is approximately one second, but the resulting savings can add up to minutes.

Overall Results

So, let’s look at how this all comes together with the various optimizations, device types and connectivity options. The following table sums it all up.

| Original website | Add image resizing | Add adaptive JS and CSS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Page size | Loading time | Page size | Loading time | Page size | Loading time | |

| Desktop (high-speed) | 1027 KB | 3s | 921 KB | 3s | 921 KB | 3s |

| Desktop (56k modem) | 1027 KB | 3m 27s | 921 KB | 3m 14s | 921 KB | 2m 05s |

| iPhone 3G | 1027 KB | 14s | 253 KB | 7s | 253 KB | 6s |

| iPhone GPRS | 1027 KB | 2m 30s | 253 KB | 40s | 253 KB | 40s |

| Feature phone (2G) | 1027 KB | ∞ | 203 KB | 35s | 87 KB | 25s |

| Original website | Add network adaptivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Page size | Loading time | Page size | Loading time | |

| Desktop (high-speed) | 1027 KB | 3s | 921 KB | 3s |

| Desktop (56k modem) | 1027 KB | 3m 27s | 227 KB | 40s |

| iPhone 3G | 1027 KB | 14s | 153 KB | 5s |

| iPhone GPRS | 1027 KB | 2m 30s | 153 KB | 25s |

| Feature phone (2G) | 1027 KB | ∞ | 25 KB | 12s |

These loading times are all worst-case scenarios, tested with an empty cache. Subsequent page loads as you traverse the website will feel much faster.

With all of these optimizations in place, we now have a more sensible responsive design that scales dynamically in richness and size, from 1 MB all the way down to 25 KB, all in. The website incorporates the best of RWD and server-side optimizations to yield a dynamic range factor of over 40.

The website is now responsive to multiple factors, not just one: screen size, device capabilities and network performance. As a result, the reach of this page has extended from desktop and smart devices in well-connected locations to almost everything, everywhere, regardless of connection type. Apart from getting our image size tags to populate dynamically, we didn’t have to do much work to make this happen.

Website before optimization on various devices:

Desktop: 1360 × 768 pixels, page size 1,027 KB

iPhone: 320 × 480 pixels, page size 1,027 KB

Nokia 6300: 240 × 320 pixels, page size 1,027 KB

Website after optimization on various devices:

Desktop: 1360 × 768 pixels, page size 1,027 KB

iPhone: 320 × 480 pixels, page size 153 KB

Nokia 6300: 240 × 320 pixels, page size 25 KB

Circling back to the page linked at the top of this article, Chris Zacharias, speaking of his experience optimizing YouTube’s page weight, says the following:

"[Previously], entire populations of people simply could not use YouTube because it took too long to see anything... By keeping your code small and lightweight, you can literally open your product up to new markets."

By using some of the techniques outlined in this article, you might be able to achieve similar results for your website.

- Download the source of the various versions of the sample website (ZIP), mobiForge

Notes

PageSpeed has a couple of other useful tricks up its sleeve.

Many thanks to Jonathan Heron of McCannBlue for reviewing this article.

Further Reading

- Picture Perfect: Meet Pixo, A Photo Editor For Your End Users

- Building Complex Forms In Vue

- Lesser-Known And Underused CSS Features In 2022

- Art Direction For The Web Using CSS Shapes

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now