10 Things Every WordPress Plugin Developer Should Know

Having written several plugins myself, I’ve come to learn many (but certainly not all) of the ins-and-outs of WordPress plugin development, and this article is a culmination of the things I think every WordPress plugin developer should know. Oh, and keep in mind everything you see here is compatible with WordPress 3.0+.

Don’t Develop Without Debugging

The first thing you should do when developing a WordPress plugin is to enable debugging, and I suggest leaving it on the entire time you’re writing plugin code. When things go wrong, WordPress raises warnings and error messages, but if you can’t see them then they might as well have not been raised at all.

Enabling debugging also turns on WordPress notices, which is important because that’s how you’ll know if you’re using any deprecated functions. Deprecated functions may be removed from future versions of WordPress, and just about every WordPress release contains functions slated to die at a later date. If you see that you are using a deprecated function, it’s best to find its replacement and use that instead.

How to Enable Debugging

By default, WordPress debugging is turned off, so to enable it, open wp-config.php (tip: make a backup copy of this file that you can revert to later if needed) in the root of your WordPress installation and look for this line:

define('WP_DEBUG', false);Replace that line with the following:

// Turns WordPress debugging on

define('WP_DEBUG', true);

// Tells WordPress to log everything to the /wp-content/debug.log file

define('WP_DEBUG_LOG', true);

// Doesn’t force the PHP 'display_errors' variable to be on

define('WP_DEBUG_DISPLAY', false);

// Hides errors from being displayed on-screen

@ini_set('display_errors', 0);With those lines added to your wp-config.php file, debugging is fully enabled. Here’s an example of a notice that got logged to /wp-content/debug.log for using a deprecated function:

[15-Feb-2011 20:09:14] PHP Notice: get_usermeta is deprecated since version 3.0! Use get_user_meta() instead. in C:CodePluginswordpresswp-includesfunctions.php on line 3237

With debugging enabled, keep a close eye on /wp-content/debug.log as you develop your plugin. Doing so will save you, your users, and other plugin developers a lot of headaches.

How to Log Your Own Debug Statements

So what about logging your own debug statements? Well, the simplest way is to use echo and see the message on the page. It’s the quick-and-dirty-hack way to debug, but everyone has done it one time or another. A better way would be to create a function that does this for you, and then you can see all of your own debug statements in the debug.log file with everything else.

Here’s a function you can use; notice that it only logs the message if WP_DEBUG is enabled:

function log_me($message) {

if (WP_DEBUG === true) {

if (is_array($message) || is_object($message)) {

error_log(print_r($message, true));

} else {

error_log($message);

}

}

}And then you can call the log_me function like this:

log_me(array('This is a message' => 'for debugging purposes'));

log_me('This is a message for debugging purposes');Use the BlackBox Debug Bar Plugin

I only recently discovered this plugin, but it’s already been a huge help as I work on my own plugins. The BlackBox plugin adds a thin black bar to the top of any WordPress post or page, and provides quick access to errors, global variables, profile data, and SQL queries.

![]()

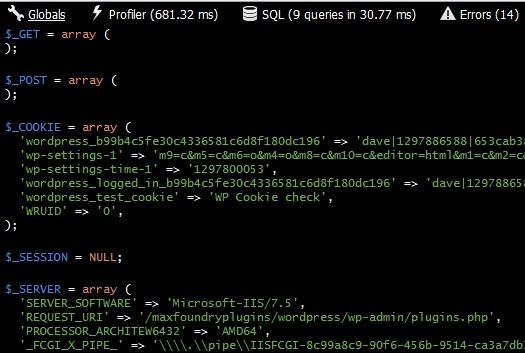

Clicking on the Globals tab in the bar shows all of the global variables and their values that were part of the request, essentially everything in the $_GET, $_POST, $_COOKIE, $_SESSION, and $_SERVER variables:

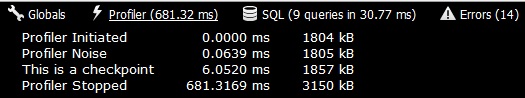

The next tab is the Profiler, which displays the time that passed since the profiler was started and the total memory WordPress was using when the checkpoint was reached:

You can add your own checkpoints to the Profiler by putting this line of code anywhere in your plugin where you want to capture a measurement:

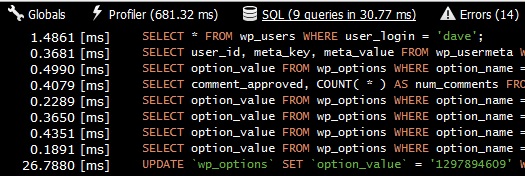

apply_filters('debug', 'This is a checkpoint');Perhaps the most valuable tab in the BlackBox plugin is the SQL tab, which shows you all of the database queries that executed as part of the request. Very useful for determining long-running database calls:

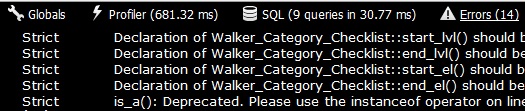

And finally we have the Errors tab, which lists all of the notices, warnings, and errors that occurred during the request:

By providing quick access to essential debug information, the BlackBox plugin is a big-timer when it comes to debugging your WordPress plugin.

Prefix Your Functions

One of the first things that bit me when I started developing WordPress plugins was finding out that other plugin developers sometimes use the same names for functions that I use. For example, function names like copy_file(), save_data(), and database_table_exists() have a decent chance of being used by other plugins in addition to yours.

The reason for this is because when WordPress activates a plugin, PHP loads the functions from the plugin into the WordPress execution space, where all functions from all plugins live together. There is no separation or isolation of functions for each plugin, which means that each function must be uniquely named.

Fortunately, there is an easy way around this, and it’s to name all of your plugin functions with a prefix. For example, the common functions I mentioned previously might now look like this:

function myplugin_copy_file() {

}

function myplugin_save_data() {

}

function myplugin_database_table_exists() {

}Another common naming convention is to use a prefix that is an abbreviation of your plugin’s name, such as “My Awesome WordPress Plugin”, in which case the function names would be:

function mawp_copy_file() {

}

function mawp_save_data() {

}

function mawp_database_table_exists() {

}There is one caveat to this, however. If you use PHP classes that contain your functions (which in many cases is a good idea), you don’t really have to worry about clashing with functions defined elsewhere. For example, let’s say you have a class in your plugin named “CommonFunctions” with a copy_file() function, and another plugin has the same copy_file() function defined, but not in a class. Invoking the two functions would look similar to this:

// Calls the copy_file() function from your class

$common = new CommonFunctions();

$common->copy_file();

// Calls the copy_file() function from the other plugin

copy_file();By using classes, the need to explicitly prefix your functions goes away. Just keep in mind that WordPress will raise an error if you use a function name that’s already taken, so keep an eye on the debug.log file to know if you’re in the clear or not.

Global Paths Are Handy

Writing the PHP code to make your plugin work is one thing, but if you want to make it look and feel good at the same time, you’ll need to include some images, CSS, and perhaps a little JavaScript as well (maybe in the form of a jQuery plugin). And in typical fashion, you’ll most likely organize these files into their own folders, such as “images”, “css”, and “js”.

That’s all well and good, but how should you code your plugin so that it can always find those files, no matter what domain the plugin is running under? The best way that I’ve found is to create your own global paths that can be used anywhere in your plugin code.

For example, I always create four global variables for my plugins, one each for the following:

- The path to the theme directory

- The name of the plugin

- The path to the plugin directory

- The url of the plugin

For which the code looks like this:

if (!defined('MYPLUGIN_THEME_DIR'))

define('MYPLUGIN_THEME_DIR', ABSPATH . 'wp-content/themes/' . get_template());

if (!defined('MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_NAME'))

define('MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_NAME', trim(dirname(plugin_basename(__FILE__)), '/'));

if (!defined('MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_DIR'))

define('MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_DIR', WP_PLUGIN_DIR . '/' . MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_NAME);

if (!defined('MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_URL'))

define('MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_URL', WP_PLUGIN_URL . '/' . MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_NAME);

Having these global paths defined lets me write the code below in my plugin anywhere I need to, and I know it will resolve correctly for any website that uses the plugin:

$image = MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_URL . '/images/my-image.jpg';

$style = MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_URL . '/css/my-style.css';

$script = MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_URL . '/js/my-script.js';Store the Plugin Version for Upgrades

When it comes to WordPress plugins, one of the things you’ll have to deal with sooner or later is upgrades. For instance, let’s say the first version of your plugin required one database table, but the next version requires another table. How do you know if you should run the code that creates the second database table?

I suggest storing the plugin version in the WordPress database so that you can read it later to decide certain upgrade actions your plugin should take. To do this, you’ll need to create a couple more global variables and invoke the add_option() function:

if (!defined('MYPLUGIN_VERSION_KEY'))

define('MYPLUGIN_VERSION_KEY', 'myplugin_version');

if (!defined('MYPLUGIN_VERSION_NUM'))

define('MYPLUGIN_VERSION_NUM', '1.0.0');

add_option(MYPLUGIN_VERSION_KEY, MYPLUGIN_VERSION_NUM);I certainly could have simply called add_option(‘myplugin_version’, ‘1.0.0’); without the need for the global variables, but like the global path variables, I’ve found these just as handy for using in other parts of a plugin, such as a Dashboard or About page.

Also note that update_option() could have been used instead of add_option(). The difference is that add_option() does nothing if the option already exists, whereas update_option() checks to see if the option already exists, and if it doesn’t, it will add the option to the database using add_option(); otherwise, it updates the option with the value provided.

Then, when it comes time to check whether or not to perform upgrade actions, your plugin will end up with code that looks similar to this:

$new_version = '2.0.0';

if (get_option(MYPLUGIN_VERSION_KEY) != $new_version) {

// Execute your upgrade logic here

// Then update the version value

update_option(MYPLUGIN_VERSION_KEY, $new_version);

}Use dbDelta() to Create/Update Database Tables

If your plugin requires its own database tables, you will inevitably need to modify those tables in future versions of your plugin. This can get a bit tricky to manage if you’re not careful, but WordPress helps alleviate this problem by providing the dbDelta() function.

A useful feature of the dbDelta() function is that it can be used for both creating and updating tables, but according to the WordPress codex page “Creating Tables with Plugins”, it’s a little picky:

- You have to put each field on its own line in your SQL statement.

- You have to have two spaces between the words PRIMARY KEY and the definition of your primary key.

- You must use the keyword KEY rather than its synonym INDEX and you must include at least one KEY.

Knowing these rules, we can use the function below to create a table that contains an ID, a name, and an email:

function myplugin_create_database_table() {

global $wpdb;

$table = $wpdb->prefix . 'myplugin_table_name';

$sql = "CREATE TABLE " . $table . " (

id INT NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

name VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL DEFAULT ’,

email VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL DEFAULT ’,

UNIQUE KEY id (id)

);";

require_once(ABSPATH . 'wp-admin/includes/upgrade.php');

dbDelta($sql);

}Important: The dbDelta() function is found in wp-admin/includes/upgrade.php, but it has to be included manually because it’s not loaded by default.

So now we have a table, but in the next version we need to expand the size of the name column from 100 to 250. Fortunately dbDelta() makes this straightforward, and using our upgrade logic previously, the next version of the plugin will have code similar to this:

$new_version = '2.0.0';

if (get_option(MYPLUGIN_VERSION_KEY) != $new_version) {

myplugin_update_database_table();

update_option(MYPLUGIN_VERSION_KEY, $new_version);

}

function myplugin_update_database_table() {

global $wpdb;

$table = $wpdb->prefix . 'myplugin_table_name';

$sql = "CREATE TABLE " . $table . " (

id INT NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

name VARCHAR(250) NOT NULL DEFAULT ’, // Bigger name column

email VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL DEFAULT ’,

UNIQUE KEY id (id)

);";

require_once(ABSPATH . 'wp-admin/includes/upgrade.php');

dbDelta($sql);

}While there are other ways to create and update database tables for your WordPress plugin, it’s hard to ignore the flexibility of the dbDelta() function.

Know the Difference Between include, include_once, require, and require_once

There will come a time during the development of your plugin where you will want to put code into other files so that maintaining your plugin is a bit easier. For instance, a common practice is to create a functions.php file that contains all of the shared functions that all of the files in your plugin can use.

Let’s say your main plugin file is named myplugin.php and you want to include the functions.php file. You can use any of these lines of code to do it:

include 'functions.php';

include_once 'functions.php';

require 'functions.php';

require_once 'functions.php';But which should you use? It mostly depends on your expected outcome of the file not being there.

- include: Includes and evaluates the specified file, throwing a warning if the file can’t be found.

- include_once: Same as include, but if the file has already been included it will not be included again.

- require: Includes and evaluates the specified file (same as include), but instead of a warning, throws a fatal error if the file can’t be found.

- require_once: Same as require, but if the file has already been included it will not be included again.

My experience has been to always use include_once because a) how I structure and use my files usually requires them to be included once and only once, and b) if a required file can’t be found I don’t expect parts of the plugin to work, but it doesn’t need to break anything else either.

Your expectations may vary from mine, but it’s important to know the subtle differences between the four ways of including files.

Use bloginfo(‘wpurl’) Instead of bloginfo(‘url’)

By and large, WordPress is installed in the root folder of a website; it’s standard operating procedure. However, every now and then you’ll come across websites that install WordPress into a separate subdirectory under the root. Seems innocent enough, but the location of WordPress is critically important.

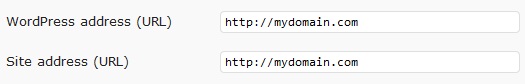

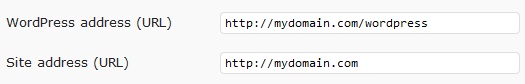

To demonstrate, in the “General Settings” section of the WordPress admin panel, you’ll find the “WordPress address (URL)” and “Site address (URL)” settings, and for sites where WordPress is installed into the root directory, they will have the exact same values:

But for sites where WordPress is installed into a subdirectory under the root (in this case a “wordpress” subdirectory), their values will be different:

At this stage it’s important to know the following:

- bloginfo(‘wpurl’) equals the “WordPress address (URL)” setting

- bloginfo(‘url’) equals the “Site address (URL)” setting

Where this matters is when you need to build URLs to certain resources or pages. For example, if you want to provide a link to the WordPress login screen, you could do this:

// URL will be https://mydomain.com/wp-login.php

<a href="<?php bloginfo('url') ?>/wp-login.php">Login</a>But that won’t resolve to the correct URL in the scenario such as the one above where WordPress is installed to the “wordpress” subdirectory. To do this correctly, you must use bloginfo(‘wpurl’) instead:

// URL will be https://mydomain.com/wordpress/wp-login.php

<a href="<?php bloginfo('wpurl') ?>/wp-login.php">Login</a>Using bloginfo(‘wpurl’) instead of bloginfo(‘url’) is the safest way to go when building links and URLs inside your plugin because it works in both scenarios: when WordPress is installed in the root of a website and also when it’s installed in a subdirectory. Using bloginfo(‘url’) only gets you the first one.

How and When to Use Actions and Filters

WordPress allows developers to add their own code during the execution of a request by providing various hooks. These hooks come in the form of actions and filters:

- Actions: WordPress invokes actions at certain points during the execution request and when certain events occur.

- Filters: WordPress uses filters to modify text before adding it to the database and before displaying it on-screen.

The number of actions and filters is quite large, so we can’t get into them all here, but let’s at least take a look at how they are used.

Here’s an example of how to use the admin_print_styles action, which allows you to add your own stylesheets to the WordPress admin pages:

add_action('admin_print_styles', 'myplugin_admin_print_styles');

function myplugin_admin_print_styles() {

$handle = 'myplugin-css';

$src = MYPLUGIN_PLUGIN_URL . '/styles.css';

wp_register_style($handle, $src);

wp_enqueue_style($handle);

}And here’s how you would use the the_content filter to add a “Follow me on Twitter!” link to the bottom of every post:

add_filter('the_content', 'myplugin_the_content');

function myplugin_the_content($content) {

$output = $content;

$output .= '<p>';

$output .= '<a href="https://twitter.com/username">Follow me on Twitter!</a>';

$output .= '</p>';

return $output;

}

It’s impossible to write a WordPress plugin without actions and filters, and knowing what’s available to use and when to use them can make a big difference. See the WordPress codex page “Plugin API/Action Reference” for the complete list of actions and the page “Plugin API/Filter Reference” for the complete list of filters.

Tip: Pay close attention to the order in which the actions are listed on its codex page. While not an exact specification, my experimentation and trial-and-error has shown it to be pretty close to the order in which actions are invoked during the WordPress request pipeline.

Add Your Own Settings Page or Admin Menu

Many WordPress plugins require users to enter settings or options for the plugin to operate properly, and the way plugin authors accomplish this is by either adding their own settings page to an existing menu or by adding their own new top-level admin menu to WordPress.

How to Add a Settings Page

A common practice for adding your own admin settings page is to use the add_menu() hook to call the add_options_page() function:

add_action('admin_menu', 'myplugin_admin_menu');

function myplugin_admin_menu() {

$page_title = 'My Plugin Settings';

$menu_title = 'My Plugin';

$capability = 'manage_options';

$menu_slug = 'myplugin-settings';

$function = 'myplugin_settings';

add_options_page($page_title, $menu_title, $capability, $menu_slug, $function);

}

function myplugin_settings() {

if (!current_user_can('manage_options')) {

wp_die('You do not have sufficient permissions to access this page.');

}

// Here is where you could start displaying the HTML needed for the settings

// page, or you could include a file that handles the HTML output for you.

}

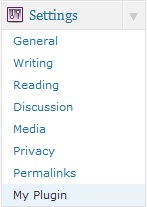

By invoking the add_options_page() function, we see that the “My Plugin” option has been added to the built-in Settings menu in the WordPress admin panel:

The add_options_page() function is really just a wrapper function on top of the add_submenu_page() function, and there are other wrapper functions that do similar work for the other sections of the WordPress admin panel:

- add_dashboard_page()

- add_posts_page()

- add_media_page()

- add_links_page()

- add_pages_page()

- add_comments_page()

- add_theme_page()

- add_plugins_page()

- add_users_page()

- add_management_page()

How to Add a Custom Admin Menu

Those wrapper functions work great, but what if you wanted to create your own admin menu section for your plugin? For example, what if you wanted to create a “My Plugin” admin section with more than just the Settings page, such as a Help page? This is how you would do that:

add_action('admin_menu', 'myplugin_menu_pages');

function myplugin_menu_pages() {

// Add the top-level admin menu

$page_title = 'My Plugin Settings';

$menu_title = 'My Plugin';

$capability = 'manage_options';

$menu_slug = 'myplugin-settings';

$function = 'myplugin_settings';

add_menu_page($page_title, $menu_title, $capability, $menu_slug, $function);

// Add submenu page with same slug as parent to ensure no duplicates

$sub_menu_title = 'Settings';

add_submenu_page($menu_slug, $page_title, $sub_menu_title, $capability, $menu_slug, $function);

// Now add the submenu page for Help

$submenu_page_title = 'My Plugin Help';

$submenu_title = 'Help';

$submenu_slug = 'myplugin-help';

$submenu_function = 'myplugin_help';

add_submenu_page($menu_slug, $submenu_page_title, $submenu_title, $capability, $submenu_slug, $submenu_function);

}

function myplugin_settings() {

if (!current_user_can('manage_options')) {

wp_die('You do not have sufficient permissions to access this page.');

}

// Render the HTML for the Settings page or include a file that does

}

function myplugin_help() {

if (!current_user_can('manage_options')) {

wp_die('You do not have sufficient permissions to access this page.');

}

// Render the HTML for the Help page or include a file that does

}Notice that this code doesn’t use any of the wrapper functions. Instead, it calls add_menu_page() (for the parent menu page) and add_submenu_page() (for the child pages) to create a separate “My Plugin” admin menu that contains the Settings and Help pages:

One advantage of adding your own custom menu is that it’s easier for users to find the settings for your plugin because they aren’t buried within one of the built-in WordPress admin menus. Keeping that in mind, if your plugin is simple enough to only require a single admin page, then using one of the wrapper functions might make the most sense. But if you need more than that, creating a custom admin menu is the way to go.

Provide a Shortcut to Your Settings Page with Plugin Action Links

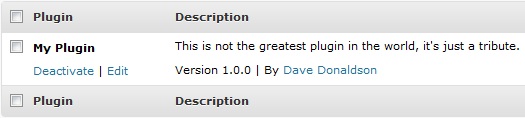

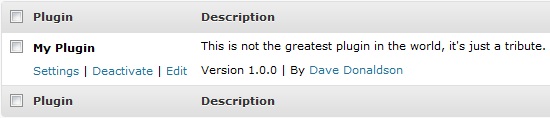

In much the same way that adding your own custom admin menu helps give the sense of a well-rounded plugin, plugin action links work in the same fashion. So what are plugin action links? It’s best to start with a picture:

See the “Deactivate” and “Edit” links underneath the name of the plugin? Those are plugin action links, and WordPress provides a filter named plugin_action_links for you to add more. Basically, plugin action links are a great way to add a quick shortcut to your most commonly used admin menu page.

Keeping with our Settings admin page, here’s how we would add a plugin action link for it:

add_filter('plugin_action_links', 'myplugin_plugin_action_links', 10, 2);

function myplugin_plugin_action_links($links, $file) {

static $this_plugin;

if (!$this_plugin) {

$this_plugin = plugin_basename(__FILE__);

}

if ($file == $this_plugin) {

// The "page" query string value must be equal to the slug

// of the Settings admin page we defined earlier, which in

// this case equals "myplugin-settings".

$settings_link = '<a href="' . get_bloginfo('wpurl') . '/wp-admin/admin.php?page=myplugin-settings">Settings</a>';

array_unshift($links, $settings_link);

}

return $links;

}With this code in place, now when you view your plugins list you’ll see this:

Here we provided a plugin action link to the Settings admin page, which is the same thing as clicking on Settings from our custom admin menu. The benefit of the plugin action link is that users see it immediately after they activate the plugin, thus adding to the overall experience.

Additional Resources

I’ve covered a lot in this article, but there’s plenty more out there to keep you busy awhile. The most comprehensive documentation for WordPress plugin development can be found on the WordPress Codex, a huge collection of pages documenting everything that is WordPress.

Further Reading

- Making A WordPress Plugin That Uses Service APIs

- How Commercial Plugin Developers Are Using The Repository

- How To Improve Your WordPress Plugin’s Readme.txt

I also suggest reading Joost de Valk’s article “Lessons Learned From Maintaining a WordPress Plug-In”, which provides more good tips on WordPress plugin development.

Agent Ready is the new Headless

Agent Ready is the new Headless SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App