The Neglected Necessities Of Design

Right now is an exciting time to be in the Web design community. Every month we seem to stumble on a new thought-provoking way to put our expanding tool set to use for our clients and the patrons of the Web. Many designers are chomping at the bit to litter their websites with new CSS, advanced HTML and ultra-engaging JavaScript. By all means, go out and use every last declaration and element you can get your hands on. Abusing, misusing and taking advantage of everything the Web could possibly offer is the best way to learn about what we can and can’t and should and shouldn’t do in future.

Whether you are excitedly exploring responsive design, diving headlong into accessibility, building a typographic masterpiece or seeing what level of interactivity you can achieve, all of your Web-based projects should have a common core. All of the new methods being discussed in the design community daily might be overwhelming, but no matter what route you ultimately take, almost any Web project you embark on today should start with solid HTML and logical CSS. This may seem like common sense, but the fact is that very, very few websites today benefit from sensationally optimized HTML and CSS and appropriately applied JavaScript.

When I say solid HTML, I don’t just mean that it validates as XHTML 1.0 Transitional. I don’t even mean that it should validate as Strict. What I mean is that your website should be void of superfluous containers, rogue classes and misused elements (both new and old). The process of building out the core components of a website may not be exciting, but this foundation is critical.

These days, we have better options. HTML5 has opened the door to a new way to structure websites, and CSS3 is revealing new methods for not only achieving advanced visuals but doing so more effectively. As designers and developers, we have failed to hold ourselves to high enough standards for too long. Websites built on an exceptional framework have simply become optional.

More Than Just HTML, CSS And JavaScript

Of course, doing things the right way is more than about understanding when to use <span> and when to use <div> or knowing what every new CSS property does and what browser it works in. Before we implement any new HTML or CSS method, we need to see how it will change the planning of our project. Building a website with the ideal structure is a process that begins at the idea stage. When the client and designer are hashing out ideas for the new project, a seasoned designer will think of these ideas in terms of the code required to make it happen. Starting a project with this mindset will help you bring up questions that lead to cleaner code. Of course, before we write any code, we have to do some research!

Know Your Audience

Information is the secret ingredient to executing a project smoothly. Any data you can gather about the perceived or target audience of a website will be crucial to the development process. Having an early grasp of browser and device usage will help you zero in on the elements and properties that you can use in your design and help you hatch a plan for how your website will progress along with its users.

Plenty of markets out there still deal with high volumes of IE7 users, which is totally fine because carefully crafted code looks beautiful in any browser. Don’t let a scarily high number of IE users distract you from using all that CSS3 and HTML5 have to offer. Unless you employ Modernizr or another polyfill (please use sparingly!), a portion of your audience may lose out on a whack of gizmos and doo-dads. But the same wonderful experience can still be crafted for every browser if you have — you guessed it! — an exquisite code base.

Plan Ahead

Every developer knows that a good website is subject to change after launch. But what makes a difference in the code is whether these changes will consist of simple content revisions, new sections of content or the addition of multimedia. One of the most common causes of bloated or invalid code is the manipulation of a website’s content after launch. Ensure that growth and expansion are a part of your wireframes and concepts where needed.

If you predict that your website will grow in future (which it should), your best bet is to make its components modular. What do I mean by modular? Well, while the form and aesthetics of the content play a vital role in setting the tone and in building a communication style, the content should still be accessible independent of the design. The first step in doing this is to relegate the style to the CSS. Now, with the advent of HTML5, we can take this to a much higher level with the new HTML elements. We can use <section> to define areas of our website that have related sets of HTML. The new <article> tag allows us to define portions of the website that should be syndicated or that can be lifted from the design. With <aside> elements, we can include information that is related to <article> or <section> but on which the content does not closely rely; if taking out an <aside> element would damage the continuity of a given section, then a <blockquote> or similar element would be better suited to the job.

Properly using these modular elements will prepare your content for its future on the Web. Applications such as Readability and Instapaper are leading the way in the trend of separating content from design by providing users with a more controllable reading experience. As we write HTML, we will see all of these elements and ideas form a foundation that is friendly to designers, users, search engines and bookmarklet apps!

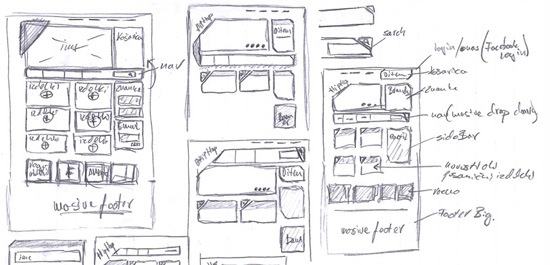

Approaching Mock-Ups And Wireframes

I’ve already said that we should consider the HTML when tossing around project ideas, so it should come as no surprise that this practice only gets ramped up when the pixels hit the page. Of course, some designers belong to the school of thought that these days we should create our mock-ups in HTML and CSS. For others, software is the weapon of choice.

No matter which path you choose, the mentality should always be the same. Design your projects with the same mindset of modularity mentioned earlier. This could mean wireframing different components with the intention of applying the same CSS class to multiple HTML elements. Or it could mean designing an <aside> for a product or service the way you would expect to see an <aside> in a blog post on the same website.

The more creative or artistic among us might dismiss this approach because it wraps a tourniquet around the veins that feed individuality. But those people, the ones who are carefully crafting their rebuttal to this argument, are the ones who will thrive under these circumstances. You see, the thing about truly creative people is that they thrive under restrictions. So, challenge yourself to build a clever and beautiful design, while maintaining this aspect of modularity and pattern-based craftsmanship. I doubt you’ll be disappointed.

Laying Down The HTML

After all of the careful planning of how your design will translate into code, it’s time to get down to the nitty gritty. Finally, we get to put our money where our keyboard is and execute some of this sleek and modular HTML that we have been bragging about and planning for.

The Basics

For some projects, our foundation will be set from the start, thanks to grid systems and boilerplates such as the highly regarded HTML5 Boilerplate. But don’t take these pre-made solutions for granted; many of them will contain more structure than you need, and none of them are a substitute for your genuine understanding of the project. Starting with a default structure saves a lot of time, but please take the time to make sure that 100% of what you start with is necessary to the project. After all, we don’t want to get off to a sloppy start, do we? The simple way to look at this is that you should know what you are putting on your website. Don’t just copy and paste someone else’s solution without knowing what it does. A common example of this is IE declarations:

<!--[if lt IE 7]> <link rel="stylesheet" href="ie6.css"> <![endif]-->

<!--[if IE 7]> <link rel="stylesheet" href="ie7.css"> <![endif]-->

<!--[if IE 8]> <link rel="stylesheet" href="ie8.css"> <![endif]-->

<!--[if gt IE 8]><!--> <link rel="stylesheet" href="normal.css"> <!--<![endif]-->

<!--[if !IE]> <link rel="stylesheet" href="normal.css"> <![endif]-->Do we really need to load different style sheets for IE7 and 8? Some projects would benefit from having only ie6.css, ie.css and normal.css. Simple websites might need only ie6.css and normal.css.

As you get off the ground with your HTML, it won’t be long before you run into problems. Of course, it happens to all of us: floats don’t behave the way we expect them to; elements don’t line up the same across browsers; and we run into good old-fashioned human error. The easiest way to isolate layout inconsistencies and to tweak design problems is usually to dig into the code and start modifying it. But this is also usually when we get into real trouble and start introducing dirty code.

Did you finally manage to align the navigation with the logo by wrapping the header in an extra div? Cool. Problem solved, right? Not quite. Does that div really need to be there, or does it force child elements to conform to positioning that could be achieved with better CSS? Before running off to the next tweak, continue to explore your problem, checking whether an extra container is the right solution or just a quick fix. With HTML and CSS, we have the power to craft a layout and style in any of several ways, not all of which are semantically correct or efficient.

More Forward Thinking

Carrying on my preaching, I’ll remind you again that at this stage of the game we need to be thinking years down the road and to consider all of the ways our website could get mangled once we leave it. We saw earlier how planing ahead for our website’s structure to take advantage of new HTML5 features enables us to build our content in a modular fashion. Now we can lean on this modular approach as we construct the HTML for our layout.

<section class="contentContainer blog">

<h1>My Blog</h1>

<article>

<hgroup>

<h1>Hello Again, World</h1>

<h5>Posted by: …</h5>

</hgroup>

<p>This is my second…</p>

<p>You may be interested…</p>

<aside>

<h2>Related Reading</h2>

<ul>

<li><a href="#">Related link 1</a></li>

…

<li><a href="#">Related link 4</a></li>

</ul>

</aside>

</article>

<article>

…

</article>

</section>

<section class="contentContainer archives">

<h1>Blog Archive</h1>

…

</section>With this structure, we see how easy it becomes to lift an <article> out of the website and get only the content we want. Along the same lines, we could easily scrap our <aside> without hurting the content because it’s a list of suggested articles that cover the same topic but don’t directly support our content. Better yet, we can apply this exact structure to a different <section> of our website with almost no effort. Our website is easy to expand, yet we retain the ability to build a unique style thanks to the different levels of distinction that HTML5 elements bring, which we wouldn’t have with a div-centered approach. Another thing we did with the .contentContainer class is begin to establish a global structure of logical and minimal CSS hooks.

In the heat of things, going overboard with classes and IDs in our HTML is easy. Any element that we foresee looking or behaving differently merits its own class, right? Not always. Moreover, any page element that relies on JavaScript for important interactivity and feedback needs a hook, too, right? In reality, this isn’t always the case. Much like CSS selectors, most JavaScript libraries have the power to drill down into our content from the top. Because more specific elements have been added to the HTML specification, we are getting ever closer to mark-up that has minimal need for CSS hooking.

Instead of applying hooks to every element that will be a little different, simply apply them to the primary sections of your page. See how far you can get with your style sheet based on these basic classes and IDs. My rule of thumb is, if you need to drill down more than four levels in the CSS, it’s time to place a new hook, for the sake of your sanity and for those who might take over the project and wonder what you were thinking. When you start to see CSS selectors that look like .sidebar section div ul li p span, you know things are getting out of hand, and you need to place a new hook in the HTML.

This minimalist approach to CSS and JavaScript hooking serves a few purposes. First, it keeps our mark-up lean and our pages quick to load.

Secondly, it enables our CSS to do all of the hard work for us. The whole point of loading a style sheet onto a website is so that one 5 KB file will shape the look and layout of an unlimited number of HTML pages, thereby saving an unlimited amount of bandwidth — yay! If our pages have fewer hooks and a modular design, then applying one theme across the entire website will require less CSS.

Speaking of less CSS, how do we achieve that?

Slim And Sexy Style Sheets

When it comes to conservative code, CSS files usually get the short end of the stick. Grabbing all of the presentation and layout information from the HTML and dumping it in the CSS has finally become a standard process for most designers. (If it isn’t yet, make it yours.) While this is the exact purpose of a style sheet, there are plenty of methods by which a designer can make sure that the CSS that loads for every page is, like the HTML, as clean and concise as possible.

CSS As A Process

For many designers, the process of building a style sheet consists of starting with the outer containers of the HTML structure and working their way in, aligning and styling as they go. How many times have you sized and centered your #wrapper element, and then moved onto aligning the logo and primary navigation in the <header>, and then continued your way down the page? This process certainly works, but there is a much better and quicker way to handle CSS. Much as we did with the HTML, we can recycle code and use a modular approach in a way that makes more sense and takes less time.

Instead of designing a style sheet with the HTML in mind, we should carry over our mindset from the rest of the design process, putting the user first. In our new and improved CSS process, let’s start with the most important and prevalent elements of our design. These will almost always be the content. The whole point of delivering clean and semantic code is to ensure that no matter what the screen, device or context of our visitor, they will have access to the fantastic message that our website is trying to convey. For this reason, we’ll start the primary portion of our style sheet with the typography.

body, select, input, textarea {

font: normal .825em/1.25em Tahoma, Geneva, sans-serif;

color: #353838;

}

h1, h2, h3, h4 {

font-family: Georgia, "Times New Roman", Times, serif;

color: #202020;

}

h1, h2 {

font-size: 1.875em;

}

h2 {

text-align: center;

font-weight: bold;

line-height: 1.5em;

border-bottom: 4px solid #e5e5e5;

-webkit-box-shadow: 0 1px 0 #b2c6e1;

-moz-box-shadow: 0 1px 0 #b2c6e1;

box-shadow: 0 1px 0 #b2c6e1;

margin: 1em 1.25em;

}

h3, h4 {

font-size: 1.25em;

margin: .75em;

}When it comes to text, we start with the most global rules and get more specific as we move down the style sheet, a pattern that should be repeated for other portions of the website.

Because typography is usually the most heavily used element on a website, it stands to reason that we should define our core font rules on a high-level element, such as the <body> element. If we want different typographic rules for headlines or certain page elements, we can declare them just after the default settings. If you have trouble figuring out which typographic declarations to add to your high-level selector and which to use as overrides, simply mark them all up and then identify which are the most common. Apply the most common declarations to the high-level element, and build specificity as you go forward.

With the typography set and the HTML structure solid, we have a website that could technically be delivered as a functional product to any device or browser. Anything we do from this point on should be to enhance the user’s experience.

For many designers, enhancing the experience starts with coloring the page. After typography, the color palette is arguably the element that most affects a website, and therefore should be next in the style sheet. I find that a good color palette is ingrained in every level of a design, and that breaking colors out into a separate section of the CSS leads to a lot of extra lines of code and a lot of selectors that are used solely for color but that have twins throughout the style sheet serving other purposes. I am not a fan of branching a single selector into different bits for the sake of lining up declarations. However, neither method is inherently good or bad. Find a system that works best for you, and maintain consistency across the project.

Finally, we get to the structure and layout of the website. With wonderful typography and eye-catching colors sprinkled throughout our website, we can line things up the way they should be and in a way that makes the website easy to read, navigate and interact with. We can continue with the method we adopted for the typography, putting the general rules first and then getting into the details later on. One thing that will hold us back is the lack of a hierarchy in HTML for anything other than typography.

Looking at the elements included in HTML4, the specification was clearly not prepared to support the complex layouts that designers and clients demand today. We had six levels of importance for headlines, but only abstract elements like <div> and <span> for structure, with no way to indicate hierarchy. HTML5 has gotten us closer, but we aren’t there yet. To make up for this, let’s look to the global class structure that we started implementing in our HTML earlier. We used the .contentContainer class to define the areas of our website that will be visual containers for our content. This class gives us the power to style a big portion of our website quickly and allows us to easily add new containers later without having to force them to fit the style of our website using CSS.

header, footer, .contentContainer {

background: #f1f1f1;

-webkit-box-shadow: 0 0 15px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.25);

-moz-box-shadow: 0 0 15px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.25);

box-shadow: 0 0 15px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.25);

border-radius: 3px;

}Reduce, Reuse, Recycle

Much like with HTML, style sheets can get pretty funky when we get to the point of adding and removing individual declarations in order to get an element to look or behave the way we want. The gracious way in which Web browsers handle CSS rules that they don’t understand or don’t need makes this practice rather common, thus bloating our style sheets. For this reason, go back through the style sheet at the end of the day and remove any rules that no longer serve a purpose. The task is a painstaking one, but as with most such tasks, plenty of tools exist to help us along.

Another task that can save size and space is to group selectors that have the same set of style declarations. From a technical standpoint, it makes sense to create a group of selectors whenever two or more share at least one declaration. I love to take advantage of grouping selectors by using something I call CSS effects. With some of the new CSS3 declarations, I’ve found that I can move the layer styles that I copy and paste in Photoshop right into my style sheets.

.mainBox, .secondaryBox, .footerBox {

background-image: -moz-linear-gradient(rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.3), rgba(0, 0, 0, 0));

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, 0% 0%, 0% 100%, from(rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.3)), to(rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)));

background-image: -webkit-linear-gradient(rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.3), rgba(0, 0, 0, 0));

background-image: -o-linear-gradient(rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.3)), to(rgba(0, 0, 0, 0));

background-image: -ms-linear-gradient(rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.3)), to(rgba(0, 0, 0, 0));

background-repeat: no-repeat;

border: 5px solid rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.2);

}We can apply this declaration stack to any element on our page to achieve a gradient. The use of RGBa allows us to retain the background colors of individual elements and to “outsource” the gradient style to a common selector.

When combined with healthy HTML practices, spending more time on the essential pieces of solid Web design results not only in faster pages and a lighter server load but, more importantly, in a user experience that thrives on any platform regardless of the design method employed. Speaking of user experience, we still need to add one important piece to this puzzle.

JavaScript’s Vital Role

Whether or not a project can accommodate new HTML5 and CSS3 features, we still turn to JavaScript to provide users with rich and meaningful experiences, including inline form validation, error handling and live page formatting. The key difference between JavaScript and traditional HTML and CSS is that the former is a programming language. Thus, JavaScript is capable of powerful results and tricky logic but is less friendly to sloppy coding and human error. This latter characteristic leads me to my main advice about using JavaScript on your new website.

Enhance, Enhance

The first rule in applying JavaScript to your website is to test failures. What happens in a browser that has JavaScript disabled? What happens if you make a request to a geo-location API that the user declines? If either of these paths make all or a portion of your website inaccessible or inoperable, then this solution would be unacceptable, and an error- and interruption-free approach would need to be found. Much like how we currently approach CSS3, JavaScript should be used as a tool to enhance the user’s experience, not as a band-aid for quick results. If you rely on it to deliver the experience, then you are setting your website up for failure.

This might make it seem like JavaScript is not worthwhile to the design process, and indeed in some situations it may not be. One of the dangers of using any dynamic or script-based solution is that they can be so much fun to implement. Designers often get caught up in how cool these tools are and get distracted from considering whether everyone would have the same experience.

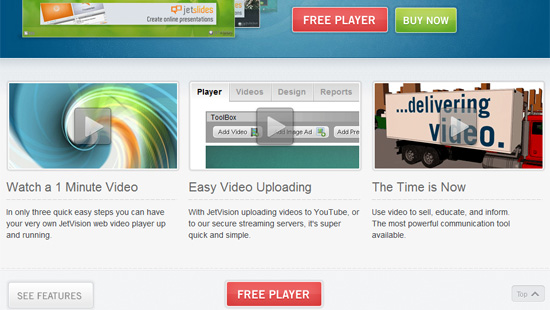

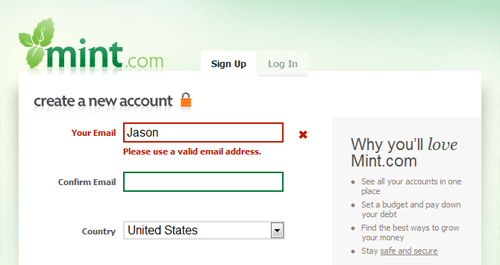

On the other hand, for adding meaningful functionality to a design, such as those mentioned earlier, JavaScript can have a truly magical effect. One of the more common examples of good JavaScript usage is inline form validation. We have all made an error in a Web form only to find out after having hit the “Submit” button, forcing us to go back and re-enter the information; in many cases, sensitive information such as passwords and credit card numbers needs to be re-entered as well. Alerting users to mistakes in real time makes online forms significantly less frustrating. Of course, we have a lot of tools and libraries out there to help us with this, as well as other great interactive features.

Keeping It Tidy

With all of these JavaScript tools at our disposal, going overboard and using as many as we can is easy, especially if we can justify their presence as enhancing the user experience. But keep in mind that with each new JavaScript library, plug-in or solution, we are adding files and lines of code to our pages that users have to download. With each bit of functionality, we have a trade-off with performance.

We can do some things to curb the performance trade-off. The most common way to optimize JavaScript is to concatenate and minify the files. Keeping multiple JavaScripts in a single optimized file reduces the number of calls that the website has to make to the server. For high-traffic solutions and clients who demand peak performance, this simple trick can save a lot of money. Of course, at a certain point, a single JavaScript file becomes too long and therefore a hindrance to the website and a nightmare to maintain.

Beyond optimization, there are techniques we can follow to keep JavaScript from weighing us down. One technique is parallel script loading. Loading your scripts in parallel will reduce blocks on the browser and save loading time, especially in older browsers that load linked resources one at a time. A great resource for this is the Head JS project.

Aside from parallel loading, developers have been taking advantage of selective loading techniques for years. This is often referred to as lazy loading, where you call external JavaScript files only where you need them. This is another resource-saving technique.

Pulling It All Together

Giving your website a clean and concise structure opens the door to myriad opportunities. Search engines will have an easier time indexing your content; screen readers and accessibility devices are less likely to be confused by the structure of your website; users on cellular networks can download your content faster; and designers will be able to expand with the latest and greatest techniques.

Let’s be honest, though. Putting a website together the right way does take more time and money up front. The whole team has to take extra caution and spend more time in the planning stages, making sure that everything is considered with the future in mind. Before a website is implemented and introduced to users, it needs to go through a scrubbing process that might not yield any changes in the front end. Finally, project stakeholders are forced to spend time thinking about scenarios (which may or may not happen) in which the natural order of their website is disrupted.

Many of these reasons have led us to implement less-than-ideal solutions in the past for the sake of meeting deadlines and budgets. But how often have we been forced to go back and fix something that wasn’t done correctly the first time? How much money are companies spending to get rid of bad practices that seemed harmless at the time but have left their websites expensive to update and maintain? Building rock-solid code and taking advantage of the power of modularity enables our websites to grow and saves much more than it costs by negating the need for another redesign just two years later.

It is for all of these reasons that the core necessities of a good website have been neglected for far too long.

Additional Resources

- Designing With Web Standards, 3rd Edition No one preaches Web standards and clean code quite like Jeffrey Zeldman. This book should be a fixture on every designer and developer’s bookshelf.

- Semantics in HTML5 In this article on A List Apart, John Allsopp breaks down how to continue developing semantic HTML with the new elements of HTML5

- Orbital Content Cameron Koczon challenges us to liberate our content from the constraints of fixed and outdated design practices. A must-read for anyone interested in designing for the shifting viewports of the expanding Internet.

Further Reading

- Typographic Design Patterns and Best Practices

- A Comprehensive Website Planning Guide

- Starting Out Organized

Agent Ready is the new Headless

Agent Ready is the new Headless

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App