The WAI Forward

It’s one thing to create a web application and quite another to keep it accessible — independent of the device that the user is using and its capabilities. That’s why Heydon Pickering, now the accessibility editor on Smashing Magazine, wrote an eBook Apps For All: Coding Accessible Web Applications, outlining the roadmap for well-designed, accessible applications.

This article is an excerpt of a chapter in the eBook that introduces many of the ideas and techniques presented. Reviewed by Steve Faulkner, it’s an eBook you definitely shouldn’t miss if you’re a developer who cares about well-structured content and inclusive interface design. – Ed.

Because the W3C’s mission from the outset has been to make the web accessible, accessibility features are built into its specifications. As responsible designers, we have the job of creating compelling web experiences without disrupting the inclusive features of a simpler design.

As Scott Jehl said:

"Accessibility is not something we add to a website, but something we start with and risk losing with each enhancement. It is to be retained."

Unfortunately, not all websites are destined to be as simple as the provocative manifesto that is “This Is a Mother****ing Website” and, as web interfaces evolve, complying with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.0) has become increasingly difficult. As we together embrace the advancements of the web and our newfound power to construct hitherto impossible web-based software, we need to tackle the accessibility of new idioms. We need to find a way to adopt new tools and techniques to keep the playing field level.

It’s time to embrace change.

ARIA: A Passion For Parity

The Web Accessibility Initiative’s (WAI) specification for Accessible Rich Internet Applications (WAI-ARIA) is an accessibility resource like WCAG 2.0, with certain notable differences. If it helps, you could think of the two resources as siblings: Both have been brought up in the same environment and have been instilled with the same basic values, but they differ in personality. WCAG 2.0 is the cautious homebody who keeps the home fires burning, while the more gregarious WAI-ARIA has ambitions to take accessibility to new territories.

Unlike WCAG 2.0, ARIA is not only a set of recommendations but a suite of attributes to be included in your HTML. Its tools enable you to alter and increase the amount of information shared about your HTML with users of assistive technologies. This is extremely useful when you’re making web apps because the roles, properties, states and relationships of elements in a web app are liable to be a lot more complex and dynamic. One way of looking at it is that ARIA gives you the tools to meet the WCAG’s requirements in web apps.

The Two Purposes Of ARIA

ARIA gives you the ability to reclassify and otherwise augment the perceived meaning (or semantics) of your HTML. That’s pretty powerful, but what is the purpose of it? ARIA has two main applications.

Remedy

ARIA can be used as a remedy to improve the information provided to assistive technology by poorly coded, unsemantic markup.

For example, a developer might use a <div> and some JavaScript to emulate a type=“checkbox”. They shouldn’t, but they might. To make this <div> actually understandable as a checkbox, the ARIA role of checkbox can be added as an attribute, making screen readers think it is, in fact, a standard checkbox. In addition, our developer must use the aria-checked attribute to indicate whether the checkbox is indeed checked.

<div class="toggle-thingy" role="checkbox" aria-checked="false" tabindex="0">Yes?</div>

Using the proper input element, type attribute and checked attribute to communicate this information would be better — they are better supported than ARIA (which is relatively modern), and the input element would be automatically focusable, like a semantic <button> (so, no need for the tabindex). Nonetheless, we can employ ARIA in this way to make quick fixes to markup, often without disturbing the design of the application.

Enhancement

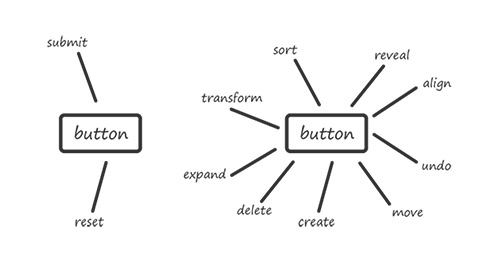

As we’ve established, web applications are more complex than simple web documents, and our use of HTML elements tends to exceed the basic semantics gifted to them. ARIA’s killer feature is its ability to help authors like you and me communicate many of these more ambitious uses in an accessible way.

Take ARIA’s aria-haspopup attribute. It represents a property of certain elements that have a hidden submenu. The owner of this property is likely to be an <a> or <button> element and, without this special attribute, that’s all it would be to the user of a screen reader: No clue would be given that the submenu exists.

<li>

<a href="#submenu" aria-haspopup="true" aria-controls="submenu1">Main link</a>

<ul id="submenu">

<li><a href="/somewhere/">Submenu link</a></li>

<li><a href="/somewhere/else/">Another link</a></li>

</ul>

</li>

Some of these ARIA attributes are expected to be replaced by simple HTML elements and attributes. As I write, the <dialog> element is being slowly adopted as the successor to the dialog and alertdialog ARIA role attributes, for example.

Where possible, superseding ARIA with plain HTML(5) is good because it simplifies the markup and centralizes the W3C’s advice. However, many attributes that communicate specific contextual information, such as the aria-haspopup and aria-controls properties in the code above, are unlikely to find as much mainstream support for inclusion as perhaps haspopup and controls will have.

As Steve Faulkner points out in “HTML5 and the Myth of WAI-ARIA Redundance”, much of ARIA will continue to exist unbested. The unique power of ARIA is to bridge the gap between the experiences of sighted and unsighted web users.

Role-Playing

A lot of my friends and colleagues are keen on tabletop role-playing games, which, in case you’re not familiar with them, are games in which participants play fictional characters who embark on quests and fight battles in fantastical worlds. Although I’m not a big exponent of these games myself, I’ve noticed similarities between the way characters are role-played in games and the way HTML elements act within web applications. Accordingly, I’ll use this role-playing metaphor to explain ARIA’s roles, properties and states in greater detail.

Don’t worry, you won’t have to be a big role-playing geek to follow along. I’m not!

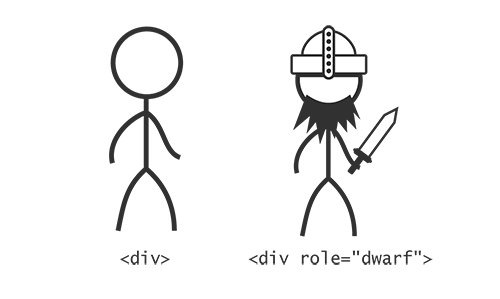

Roles

Each player in a role-playing game normally maintains a “character sheet” that lists the important characteristics of the character they are playing. In HTML, the name of the character might be the id of an element. Each must be unique.

Characters have a lot more information than that in the sheet, though. For example, characters dwelling in these fantasy worlds usually belong to one “race” or another. Common standbys are elves, dwarves and trolls. These are like HTML element types: broad groupings of participants with common characteristics.

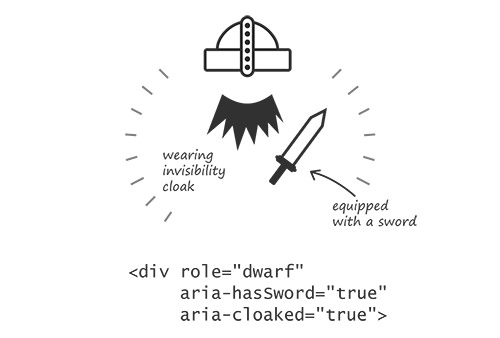

In ARIA, the role attribute overrides the element type, much like a player in a game overrides their workaday existence as a 21st-century human to become a mighty dwarf. In the example from the last section, an insipid <div> assumed the role of a checkbox by being given role=“checkbox”.

Roles in ARIA, like races in a role-playing game, are a part of a character’s identity that we might be interested in. We might expect dwarves to be strong and good at constructing machines, just like we expect a <button> to have the characteristics and behaviors already discussed. By putting role=“button” on an element that isn’t actually a <button>, we are asking assistive technologies to identify it as a button, evoking those characteristics.

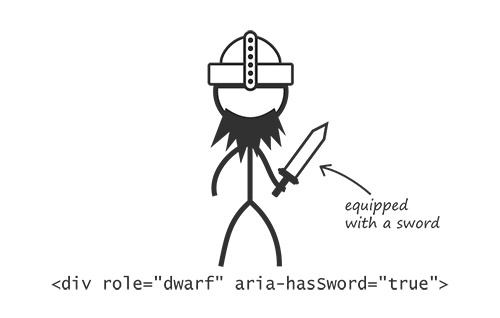

Properties

Character sheets with just names and races would be a bit limited. We’d probably be a bit uncomfortable with so much emphasis on race, too. The whole point of ARIA is that it recognizes elements not just for their generic, reductive classification. Much better to identify characters and elements by their individual assets and talents.

A typical sheet would list a set of characteristics for a character that, in one way or another, the game identifies as having a certain currency and importance. For instance, you might be an elf but one who is special for the ability to cast certain magic spells. In much the same way, we looked at an <a> element that is made special for having the property of a submenu. This would be identified to the accessibility layer, just like the basic role, via the aria-haspopup=“true” property attribute.

A huge number of properties have been specified and documented. Some are global, meaning that any element may have them, while others are reserved for particular contexts and elements. Dwarves are usually precluded from having good longbow accuracy, whereas the skill is common to elves. The aria-label that we would use to label a button is global, whereas aria-required, which denotes a required user entry, would normally be used in form fields or elements with form-field roles, such as listbox and textbox.

States

Perhaps the most important distinction between a static web document and an application is that the elements in an application tend to change — sometimes dramatically — according to user interaction and timed events. Depending on what’s happening in an application at any one time, the elements therein could be said to be in certain, often temporary, states.

In role-playing games, you have to keep tabs on the state of your character: How healthy are you? What items have you collected? Who have you befriended? This is all scribbled down, erased and scribbled down some more on the character sheet. Keeping track of the state of interactive elements is important for accessibility, too.

In your application, the state of an element is usually represented visually. In role-playing games and in screen-reader buffers, this is not the case: It has to be imagined. If your dwarf character has donned their magic cloak of invisibility, you’d probably want to write this down on the character sheet so that you remember. Similarly, writing the aria-hidden attribute on an element ensures that the accessible state of invisibility is recorded properly.

States such as aria-expanded are announced according to a value of true or false. An item with aria-expanded=“false” is announced by JAWS and NVDA Windows screen readers as “collapsed.” If — or, rather, when — it is set to aria-expanded=“true”, then the item will be announced as “expanded.”

Our First ARIA Widget

It’s about time we put everything we’ve learned about roles, properties and states into practice and build our first ARIA widget.

The term “widget” is often used in JavaScript development to denote a singular pocket of script-enabled interactive functionality. Mercifully, the ARIA definition corresponds, and ARIA widgets can be thought of as JavaScript widgets that have been made accessible with appropriate ARIA attributes.

Let’s make a simple toolbar — a group of button controls that enable us to organize some content. In this case, we’ll set up controls to sort content alphabetically and reverse alphabetically. Fortunately, we have access to the W3C’s guide on authoring ARIA widgets, “General Steps for Building an Accessible Widget With WAI-ARIA,” which covers a similar example for a toolbar.

The Toolbar Role

There’s no such thing as a <toolbar> element in HTML, unless you create one as a web component. In any case, because there’s no standard element for toolbars, we need to include the toolbar role in our toolbar’s parent element. This marks the scope of the widget:

<div role="toolbar">

/* toolbar functionality goes here */

</div>

(Note: A <menu> element takes a type of toolbar, but it has not been adopted by browser vendors so is unable to provide the information we need.)

The toolbar’s purpose in our design should be obvious from its visual relationship to the content it affects. This won’t communicate anything aurally, however, so we should provide an accessible name for our toolbar via the now familiar aria-label property. That’s one role and one property so far.

<div role="toolbar" aria-label="sorting options">

/* toolbar functionality goes here */

</div>

Now let’s add the buttons that will be our controls.

<div role="toolbar" aria-label="sorting options">

<button>A to Z</button>

<button>Z to A</button>

</div>

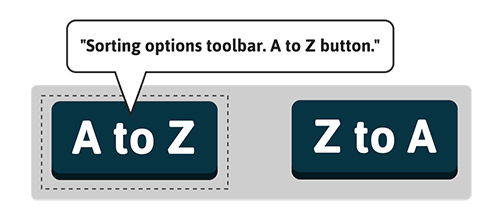

Even without the additional widget properties and states, we’ve already improved the user’s recognition of the toolbar: Using the NVDA screen reader or the JAWS screen reader with Firefox, when a user focuses the first button, they are informed that they’re inside a toolbar and — thanks to the aria-label — told what it is for.

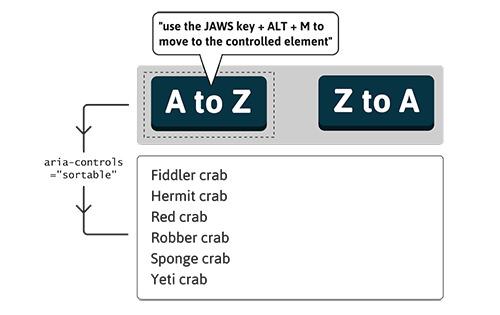

The Relationship

So far, we haven’t actually connected our toolbar to the content it controls. We need a relationship attribute, which is a special kind of property attribute that communicates a relationship between elements. Our widget is used to control the content, to manipulate and reorganize it, so we’ll go with aria-controls. We’ll join the dots using an id value, just as we did in the earlier example of the popup menu.

<div role="toolbar" aria-label="sorting options" aria-controls="sortable">

<button>A to Z</button>

<button>Z to A</button>

</div>

<ul id="sortable">

<li>Fiddler crab</li>

<li>Hermit crab</li>

<li>Red crab</li>

<li>Robber crab</li>

<li>Sponge crab</li>

<li>Yeti crab</li>

</ul>

Note that we’ve added aria-controls to the toolbar itself, not to each individual button. Both would be acceptable, but using it just the once is more succinct, and the buttons should each be considered individual components that belong to the controlling toolbar. If we want to check which properties and states are supported for widget roles like toolbar, the specification provides a list of “inherited states and properties” in each case. Consult this when you build a widget. As you will see, aria-controls is an inherited property of toolbar.

Some screen readers do very little explicitly with this relationship of information, while others are quite outspoken. JAWS actually announces a keyboard command to enable the user to move focus to the controlled element: “Use JAWS key + Alt + M to move to controlled element.” Once you’ve affected it, you might want to go and inspect it, and JAWS is helping you to do just that here.

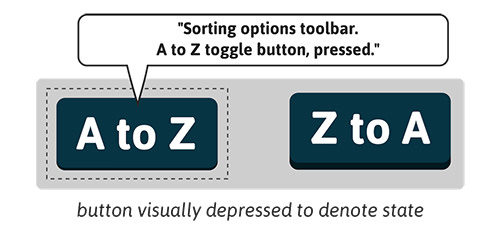

Pressed And Unpressed

Depending on which sorting option is our current preference, we could say that the button that commands that option is in a “selected,” or “pressed,” state. This is where the aria-pressed state attribute comes in, taking a value of true for pressed or false for unpressed. States are dynamic and should be toggled with JavaScript. On the page being loaded, just the first button will be set to true.

<div role="toolbar" aria-label="sorting options" aria-controls="sortable">

<button aria-pressed="true">A to Z</button>

<button aria-pressed="false">Z to A</button>

</div>

<ul id="sortable">

<li>Fiddler crab</li>

<li>Hermit crab</li>

<li>Red crab</li>

<li>Robber crab</li>

<li>Sponge crab</li>

<li>Yeti crab</li>

</ul>

Pairing the styles for active (:active) buttons with the styles for aria-pressed buttons is a good practice. Both are buttons that have been “pushed down,” whether momentarily or semi-permanently.

button:active, button[aria-pressed="true"] {

position: relative;

top: 3px; /* 3px drop */

box-shadow: 0 1px 0 #222; /* less by 3px */

}

When the user focuses a button with aria-pressed present using either NVDA or JAWS with Firefox, the button is identified as a “toggle button.” Using the latest version of JAWS and focusing a button with aria-pressed=“true” will append the word “pressed” to the announcement accordingly. In the ChromeVox screen reader for the Chrome browser, an aria-pressed=“true” button is announced as “button pressed” and aria-pressed=“false” as “button not pressed.” To a greater or lesser extent, most modern browsers and screen readers articulate helpful information about the state or potential state of these buttons.

Keyboard Controls

Not quite there yet. For toolbars — as with many ARIA widgets — the W3C recommends certain keyboard navigation features, often to emulate the equivalent in desktop software. Pressing the left and right arrow keys should switch focus between the buttons, and pressing “Tab” should move focus out of the toolbar. We’ll add tabindex=“-1” to the list and focus it using JavaScript whenever the user presses “Tab.” We do this to allow users to move directly to the list once they’ve chosen a sorting option. In a toolbar with several buttons, this could potentially save them from having to tab through a number of adjacent buttons to get to the list.

<div role="toolbar" aria-label="sorting options" aria-controls="sortable">

<button aria-pressed="true">A to Z</button>

<button aria-pressed="false">Z to A</button>

</div>

<ul id="sortable" tabindex="-1">

<li>Fiddler crab</li>

<li>Hermit crab</li>

<li>Red crab</li>

<li>Robber crab</li>

<li>Sponge crab</li>

<li>Yeti crab</li>

</ul>

$(listToSort).focus();

All Done

That concludes our ARIA widget. A live demo is ready for you to play with and test. Remember that it’s not really about sorting, per se — that’s all done with JavaScript. The aim is to make explicit the relationships and states of our application, so that whatever we are doing to our content — sorting it, editing it, searching it, creating it, recreating it — our users on keyboards and screen readers are kept in the loop.

The next chapter of the Apps For All: Coding Accessible Web Applications eBook puts the application functionality to one side and addresses how to actually find that application functionality in the first place. Mobility is a big part of accessibility online and off, so it’s important to look at different ways to help our users get around.

Further Reading

- Notes On Client-Rendered Accessibility

- Accessibility: Improving The UX For Color-Blind Users

- Making Accessibility Simpler, With Ally.js

- Inclusive Front-End Design Patterns, A New Smashing Book

Register Free Now

Register Free Now SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers