Lessons Learned After Shutting My Startup, Following A Six-Year Struggle

On 12 January 2015, Getwear, an integrated custom jeans company, processed its last order. After that, the company shut down. Despite coming up with a unique custom production process and outstanding jeans, we didn’t achieve much success. Several months — and a lot of discussion and dissection — later, I figured out why. In this article, I’m happy to share a few insights, mistakes and lessons learned, so you know what to watch out for in your projects.

It all started back in 2009, when I was finishing my marketing studies in Italy. I read a well-known article by Tim O’Reilly, “What Is Web 2.0,” and was stunned by an idea of bringing the concept to the world of “real” objects, through mass customization. Enabling users to make their own products should have transferred the power to make design decisions from the hands of the few to the hands of the people — or so I thought.

With that revolutionary idea, I approached my classmate and cofounder-to-be, who had an extensive experience in clothing production. He confirmed that producing customized clothing on a mass scale was possible.

Our professor, a former top manager of Levi’s, gave us the green light, our friends told us how cool our idea was, and we embarked on a six-year journey of uphill battle and lessons learned the hard way.

Getwear was founded on five assumptions:

- There is a demand for unique or unusual jeans.

- People want to design their own clothes.

- People would get hooked on customizing their own clothes and buy what they have designed.

- People would gladly share their designs on social media to show what they’ve designed and to earn commission.

- Social sharing would attract new customers, and the cycle would repeat.

All businesses are built on assumptions, but basing a business model on five untested ideas, each one being critical to the success of the company, was just too much.

The circumstances that made us finally close were far beyond our control, but we paved the way by not doing things right. See for yourself.

We Moved To Building Too Fast, And It Took Us Too Long

Believing in “Build it and they will come,” we skipped proper research and validation. After all, the idea seemed so wonderful that it was hard to comprehend how it could fail.

We had zero experience with web development, but we managed to raise money within a month. Naturally, we decided to get an agency to build everything for us. They were supposed to follow a set of mockups that we designed ourselves (see below); now I think those folks had a fun time working on it.

To make a long story short, in a year we launched with a custom-coded website costing more than $100,000 — that was in payments to the agency and not accounting for employee salaries or the living expenses of the founders.

Along the way, we decided to narrow our focus, cut up-front costs and launch with just one product category, the one that would yield the highest profit: jeans. Surprisingly, the production costs of one pair are not drastically different from those of a quality hoodie, yet people are accustomed to paying twice as much for jeans! Besides, denim can be customized to a great extent both in decoration and cut.

By the time the website was ready, we had a fully equipped production office in India.

We Anticipated A Viral Loop

You can see that the growth and development we anticipated relied primarily on a viral loop. Going viral is something that many entrepreneurs hope to do and never achieve, while others who do achieve it never dreamed they would.

We believed that users would enjoy designing jeans online and would gladly share their designs on social media, attracting new visitors to our website. That didn’t work out. While we had great average time on site of 3.5 minutes, users were simply not sharing.

In short, Getwear didn’t succeed because the project didn’t go viral. This was, in part, because the demand for custom clothes was more limited than we had thought.

We Had No Market Strategy

Since the company’s launch, we pivoted several times, trying to find a niche where we could grow. The first pivot was to give up on the US market, and here’s why: US jeans tend to fall into a couple of categories:

- mass-produced jeans that cost between $15 and $40 (for example, Wrangler, Levi’s, etc.);

- artisanal or designer jeans with a strong maker’s story, costing upwards of $150.

With a price point of $99 for our standard jeans, which were made in India, Getwear was out of place compared to the artisanal jeans that are handcrafted in the US (or Japan) by rugged, tattooed lumbersexuals. And we couldn’t compete with the mass-market prices of brands like Levi’s or Lee either. Severely cutting our prices wasn’t an option, because the business would cease being profitable. So, we pivoted. Again.

We Jumped Into Things Without Thinking

In this desperate situation, we decided to explore the overseas Russian market, where we had always had casual sales, despite the lack of a single Russian word on the whole website.

Because we hadn’t taken time to experiment, we decided to spend our money on the channel with the highest net coverage, without really thinking about our return on investment. Advertising on the biggest blog, run by the most famous Russian web designer, Artemy Lebedev, paid for itself within a couple of days and led us to believe we might succeed on that side of the ocean.

By that time, it was becoming clear that custom-designed jeans weren’t really interesting to anybody. Perhaps the fact that none of us had ever tried to order custom jeans ourselves should have set off alarm bells. So, we decided to refocus on quality, craft and perfect fit, which we had considered to be secondary values up until that point.

We Had No Engine Of Growth

Actually, we did, but it didn’t fit our business model. According to Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup, an engine of growth is sticky if the company lives and grows by a high percentage of repeat orders and a very high customer lifetime value (LTV).

It’s a great mechanism, and it works for companies that sell, for example, luxury goods, for which the difference between cost and retail price is high. For brands and artisans that produce goods that appeal to or are accessible to a limited audience, this allows them to live off a relatively small customer base.

Unlike them, Getwear was positioned in the mass market, and the amount of money we made on each pair was relatively low. We had to constantly acquire new customers to keep the wheels turning.

Because we didn’t go viral and there was no established demand for custom jeans, all we could rely on in the short term was paid user acquisition — that is, advertising. We tried almost everything, from smart content marketing to posters in subway cars.

Guest blogging (paid, incidentally, because that’s much more common on Russian websites) and Facebook newsfeed ads worked really well, but both channels quickly hit the ceiling (we knew we would eventually run out of popular blogs, and Facebook’s market share in Russia is pretty small).

While we managed to get great numbers (almost 6000 clicks, with a clickthrough rate of 4.36%, a cost per click of $0.13 and a conversion rate of around 1.2%), the strategy didn’t take us far and ceased to work quite quickly.

Another strategy we tried on Facebook was promoting our original content (for example, a blog post on our production unit). Unlike traditional ads, this brought great organic reach (people were sharing the content), but the conversion rate was twice as low. Needless to say, soon enough we reached a significant proportion of all active Facebook users in Russia.

Russia’s mighty Facebook rival, VK — which has more than twice as many total users and probably many times more active users — didn’t work for us. It seems that folks there are too preoccupied with cats and funny images to bother about custom jeans.

Our Last-Ditch Effort Fell Short

When nothing worked, we didn’t suspect that anything was wrong with our fundamental assumptions. Instead, we decided to boost the appeal of the product. So, we took one more leap by fully redesigning the website (this time in-house) and creating some beautiful hipster lookbooks (we do sell garments, after all).

To make sure that the website design didn’t cause problems, we hired a specialist in conversion-rate optimization to work on our sales funnel.

By the fall of 2014, it became clear that replacing the computer-generated images of jeans with properly photographed ones, adding a catalog of pre-designed jeans and running multivariate testing weren’t leading us to anything. With a conversion rate of only 0.6% and a thinning acquisition channel, our growth was stagnant.

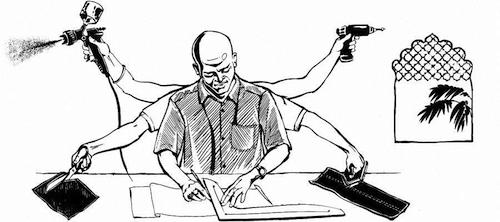

Getwear’s back end was built for a level of sales and growth that we never reached.

Everything was clearly structured. We’d built a smart production- and order-management system, and we’d integrated with intelligent pattern-making software, allowing custom patterns to be created in seconds.

This all required a lot of maintenance and R&D (Research and Development), which forced us to have qualified engineers on staff, thus increasing our burn rate. The level of sales we reached (and were struggling to increase) meant that the company was profitable only in “good” months.

The Nail In The Coffin

We had six in-house engineers and four customer-support representatives to maintain an outstanding level of quality and service. A year ago, we decided to cut costs, halt all R&D and lay off some of our employees in order to break even.

Unfortunately, political and economical realities hit hard: Following the political unrest in neighboring Ukraine, Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the collapse of the currency, Getwear jeans became twice as expensive overnight for customers in both countries.

By the end of December 2014, our financial results were seven times worse than the previous year’s. In 2013, we were selling $3000 worth of Christmas gift certificates a day — last year, just a couple in a whole month.

Getwear was dead.

Reflections

In many ways, Getwear’s story was an attempt to revive a golem. Most people, whatever their social group or сlass, don’t see the need to design their own clothes. Getwear was doomed from day one.

We started listening to user feedback only when we were already up and running, and acting on it didn’t change much. What sense would adding color and fabric options make if people simply are not interested in purchasing custom jeans online?

Customization and “consumer co-creation”, as it is formally called, is no replacement for a strong, established brand. Even a strong brand can fail trying it. As of now, there is no successful online custom jeans business. INDi Custom Denim, which was run by former top managers at Levi’s, ceased operations a year before us; two smaller startups, OriJeans and Tribe Jeans, sank in 2014; and a Kickstarter-funded project (from four years ago) hasn’t even gotten off the ground.

Levi’s shut down Original Spin, its own custom jeans operations, in 2004 — probably for good reason.

Faulty Assumptions

The assumptions on which we built our business were wrong, and we didn’t take notice. We were not honest with ourselves, and we ignored negative feedback.

We wasted a lot of time and money on creating a beautiful product that nobody needed.

Getwear had amazing customer loyalty, a ton of positive reviews and repeat sales, but we had no market to grow on and a tiny number of potential customers. While the customer lifetime value was potentially very good, people do not purchase jeans — especially good-quality ones — frequently enough to fuel sales. We struggled to find enough potential customers to keep the thing going.

Lean startups teach us that businesses work either on high volume and low margins (think mass production) or vice versa (think designer clothing). Getwear was meant to be a unicorn — a high-margin and high-volume company. In hindsight, we should have known that ignoring common sense usually leads to failure and not a $1 billion valuation.

What Else We Could Have Done

This story is not about failing to jump off a sinking ship fast enough. It’s about a failure to understand why the ship is sinking.

One of the best ways to validate a business idea is by preselling the product. The failure of crowd-funded custom jeans projects shows that it’s not that simple; to validate, one has to presell to the same target audience that the mature product will attract. If I were to start over, I would not head to Kickstarter, but rather would talk to people to learn why they purchase jeans of certain kinds and what weight a brand name carries in their decision. Knowing that, I’d most probably have come out with a better idea for my first business.

When Getwear was done, we founded a new startup, Chatra, in the crowded space of live chat software for websites. I don’t know if it will succeed, but at least we are making a tool for something we are very good at (customer support) and in a market with existing demand and strong competition, showing that the potential for growth is there. And we live and breathe customer development.

Takeaway

We believe that a company becomes successful usually not because of a revolutionary product, but because of micro-innovations. Doing something that in some way is better than others will give you a much higher chance of success than inventing a new way of doing something.

I hope some of you can learn from our mistakes.

Questions? Let me in know in the comments section below!

Summary Of Lessons Learned

- Do customer development before you start. Don’t start building before you have a clear understanding of your customers. “The Entrepreneur’s Guide to Customer Development” is a great book on that.

- Don’t aim to revolutionize something. Aim to make something better.

- Validate your fundamental assumptions as early as possible, building a minimum viable product. Don’t spend time designing detailed mockups, as we did, especially if you are new to product development; you risk wasting a lot of time and money on features that are not yet required.

- If the minimum viable product does not work as it should, don’t blame it. Check your initial assumptions instead.

- Treat the cause, not the symptom. When assumptions are invalidated, don’t try to change the facts — try coming up with new assumptions instead.

- Let it die. Working on a project that doesn’t move is painful and depressing. You can trick the media and investors into thinking that it’s going fine and that you are almost there, but don’t lie to yourself. Never ignore your gut.

Further Reading

- Designing For Start-Ups: How To Deliver The Message Across

- The Last Goodbye: How To Shut Down A Failing Product

- A Guide To Validating Product Ideas

- Do’s And Don’ts For WordPress Startups

Try if for free!

Try if for free! Register for free today!

Register for free today!

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding. Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial