How To Protect Your Users With The Privacy By Design Framework

In these politically uncertain times, developers can help to defend their users’ personal privacy by adopting the Privacy by Design (PbD) framework. These common-sense steps will become a requirement under the EU’s imminent data protection overhaul, but the benefits of the framework go far beyond legal compliance.

Note: This article is not legal advice and should not be construed as such.

Meet Privacy By Design

Let’s give credit where credit is due. The global political upheaval of the past 12 months has done more to get developers thinking about privacy, surveillance and defensive user protection than ever before. The risks and threats to ourselves, and to our users, are no longer theoretical; they are real, they are everyday, and they are frightening. One need only look at the ongoing revelations regarding Cambridge Analytica, a British company with odd links to Canada, which ran a complex data-mining operation on behalf of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign to aggregate up to 5,000 pieces of data on every American adult, to fathom what is at stake for all of us.

As developers and decision-makers, we need to do something to respond to that challenge. The political uncertainty we are living through obliges us to change the ways we approach our work. As the creators of applications and the data flows they create, we can play a critical and positive role in protecting our users from attacks on their privacy, their dignity, and even their safety.

One way we can do this is by adopting a privacy-first best-practice framework. This framework, known as Privacy by Design (PbD), is about anticipating, managing and preventing privacy issues before a single line of code is written. The best way to mitigate privacy risks, according to the PbD philosophy, is not to create them in the first place.

PbD has existed as a best-practice framework since the 1990s, but few developers are aware of it, let alone use it. That’s about to change. The EU’s data protection overhaul, GDPR, which becomes legally enforceable in May 2018, requires privacy by design as well as data protection by default across all uses and applications.

As with the previous EU data protection regime, any developer serving European customers must adhere to these data protection standards even if they themselves are not located in Europe. So, if you do business in or sell to Europe, privacy by design is now your responsibility.

This presents a monumental opportunity for developers everywhere to rethink their approach to privacy. Let’s learn what PbD is and how it works.

What Is PbD?

The PbD framework was first drawn up in Canada in the 1990s. Its originator, Dr. Ann Cavoukian, then Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, devised the framework to address the common issue of developers applying privacy fixes after a project is completed:

"The Privacy by Design framework prevents privacy-invasive events before they happen. Privacy by Design does not wait for privacy risks to materialize, nor does it offer remedies for resolving privacy infractions once they have occurred; it aims to prevent them from occurring. In short, Privacy by Design comes before-the-fact, not after."

The PbD framework has seven foundational principles:

- Privacy must be proactive, not reactive, and must anticipate privacy issues before they reach the user. Privacy must also be preventative, not remedial.

- Privacy must be the default setting. The user should not have to take actions to secure their privacy, and consent for data sharing should not be assumed.

- Privacy must be embedded into design. It must be a core function of the product or service, not an add-on.

- Privacy must be positive sum and should avoid dichotomies. For example, PbD sees an achievable balance between privacy and security, not a zero-sum game of privacy or security.

- Privacy must offer end-to-end lifecycle protection of user data. This means engaging in proper data minimization, retention and deletion processes.

- Privacy standards must be visible, transparent, open, documented and independently verifiable. Your processes, in other words, must stand up to external scrutiny.

- Privacy must be user-centric. This means giving users granular privacy options, maximized privacy defaults, detailed privacy information notices, user-friendly options and clear notification of changes.

Why PbD Matters More Than Ever

PbD has always been available for any developer to use as a voluntary best-practice framework. Its popularity has tended to be greater in cultures that have a traditionally positive view of privacy, such as Canada and many European countries. Privacy, however, is not traditionally seen as a positive value in the US, whose companies dominate the tech world. For this reason, and for too long, web development has been approached with what at times has felt like the complete opposite of a PbD viewpoint. It has almost become normal for developers to ship apps that require social media registration, that request unnecessary permissions such as microphone access and location data, and that demand access to all of a user’s contacts.

The notion of privacy by design as a voluntary concept is about to change.

In Europe, the regulation that governs all collection and processing of personal data, regardless of use, sector or situation, has had a complete overhaul. This new set of rules, known as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), is already on the books but becomes legally enforceable on 25 May 2018. Your business should already be working towards your wider GDPR compliance obligations ahead of this deadline, which will come up fast.

Crucially, GDPR makes PbD and privacy by default legal requirements within the EU. Not only will you have to develop to PbD, but you will have to document your PbD development processes. That documentation must be made available to a European regulatory authority in the event of a data breach or a consumer complaint.

“What If I Am Not In The EU?”

Remember that European data protection and privacy laws are extraterritorial: They apply to the people within Europe whom data is collected about, regardless of where the service is provided from. In other words, if you develop for European customers, you must comply with EU data protection and privacy standards for those individuals, even if you yourself are not located within Europe.

Also remember that the EU, through its data protection system, has some of the strictest and most clearly defined privacy frameworks in the world; the US, by contrast, has no overarching data protection and privacy framework at all. Culture is important to remember as well. In Europe, privacy is considered a fundamental human right. Living and developing in a country where privacy is not a fundamental human right does not negate your moral or legal obligations to those who do enjoy that right.

Developers outside the EU, therefore, should consider adopting the PbD principles within the GDPR guidelines as a development framework, despite being located outside Europe. The guidelines will give you a clear, common-sense and accountable framework to use in your development process — and that framework is a lot better than having no guidelines at all.

What Is Personal Data?

The European data protection law defines personal data as any information about a living individual who could be identified from that data, either on its own or when combined with other information.

There is also a classification called “*sensitive personal data*”, which means any information concerning an individual’s

- Racial or ethnic origin

- political opinions,

- religious or philosophical beliefs,

- trade union membership,

- health data,

- genetic data,

- biometric data,

- sex life or sexual orientation,

- past or spent criminal convictions.

The data users generate within your app is personal data. Their account information with your company is personal data. The UID identifying their device is personal data. So is their IP address, their location data, their browser fingerprint and any identifiable telemetry.

Practical PbD Implementation

For app developers, PbD compliance means factoring in data privacy by default

- at your app’s initial design stage,

- throughout its lifecycle,

- throughout the user’s engagement with your app,

- after the user’s engagement has ended,

- and after the app is mothballed.

There is no checklist of ready-made questions that will get you there; General Data Protection Regulation requires developers to come up with the questions as well as the answers. But in a proactive development environment, the answers would likely take the practical forms required under GDPR, such as the following.

Design Stage

- Create a privacy-impact assessment template for your business to use for all functions involving personal data, which we will come to a bit later on.

- Review contracts with partners and third parties to ensure the data you pass on to them is being processed in accordance with PbD and GDPR.

- Don’t require unnecessary app permissions, especially those that imply privacy invasion, such as access to contacts or to the microphone.

- Audit the security of your systems, which we will also come to shortly.

Lifecycle

- Minimize the amount of collected data.

- Minimize the amount of data shared with third parties.

- Where possible, pseudonymize personal data.

- Revisit contact forms, sign-up pages and customer-service entry points.

- Enable the regular deletion of data created through these processes.

User Engagement

- Provide clear privacy- and data-sharing notices.

- Embed granular opt-ins throughout those notices.

- Don’t require social media registration to access the app.

- Don’t enable social media sharing by default.

- Separate consent for essential third-party data sharing from consent for analytics and advertising.

End Of Engagement And Mothballing

- Periodically remind users to review and refresh their privacy settings.

- Allow users to download and delete old data.

- Delete the data of users who have closed their accounts.

- Delete all user data when the app’s life comes to an end.

PbD In Action

Good PbD practice, and its absence, is easy to spot if you know what you are looking for.

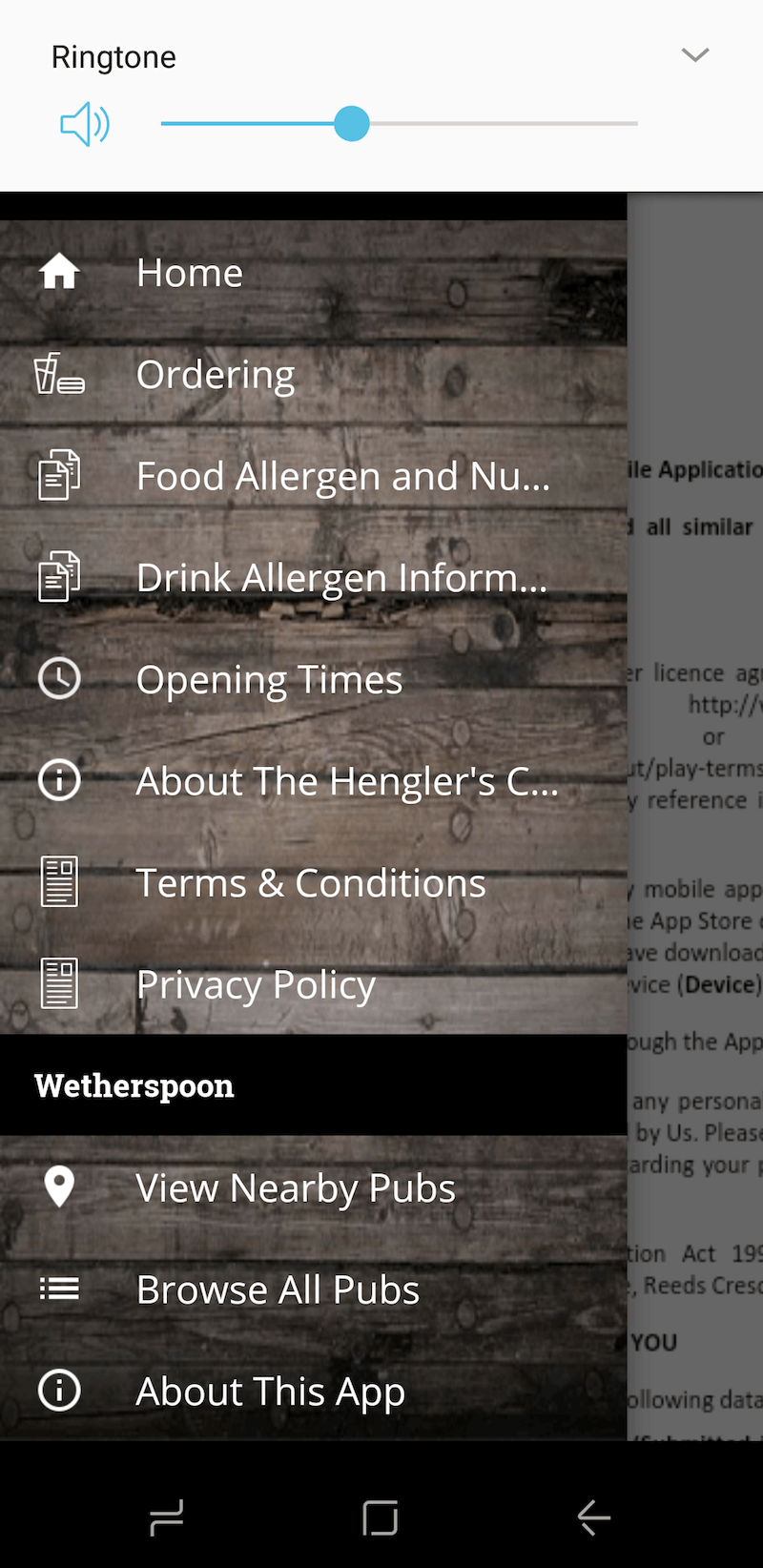

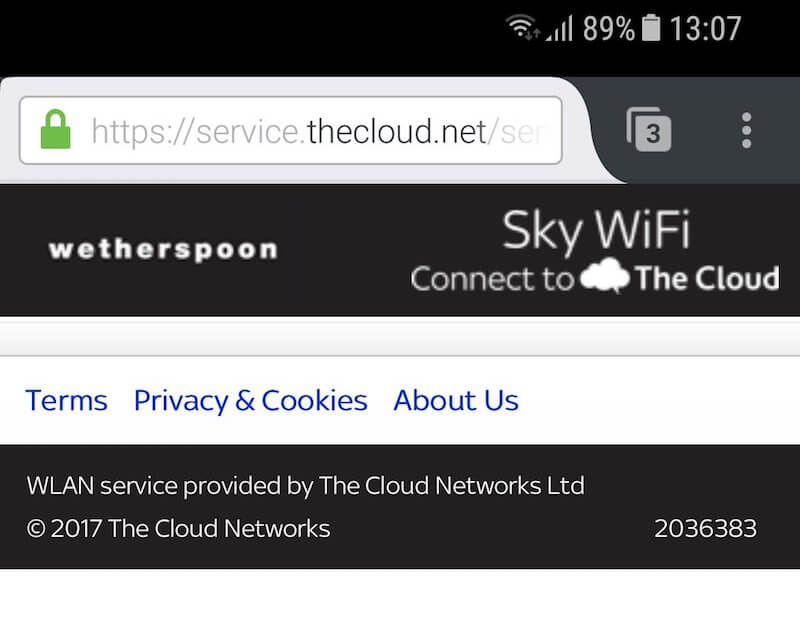

Let’s give this popular UK pub chain’s app a quick PbD audit.

The app has no settings page, which suggests no user control over privacy. This implies that downloading the app entails granting consent for data-sharing, which does not meet the second PbD principle.

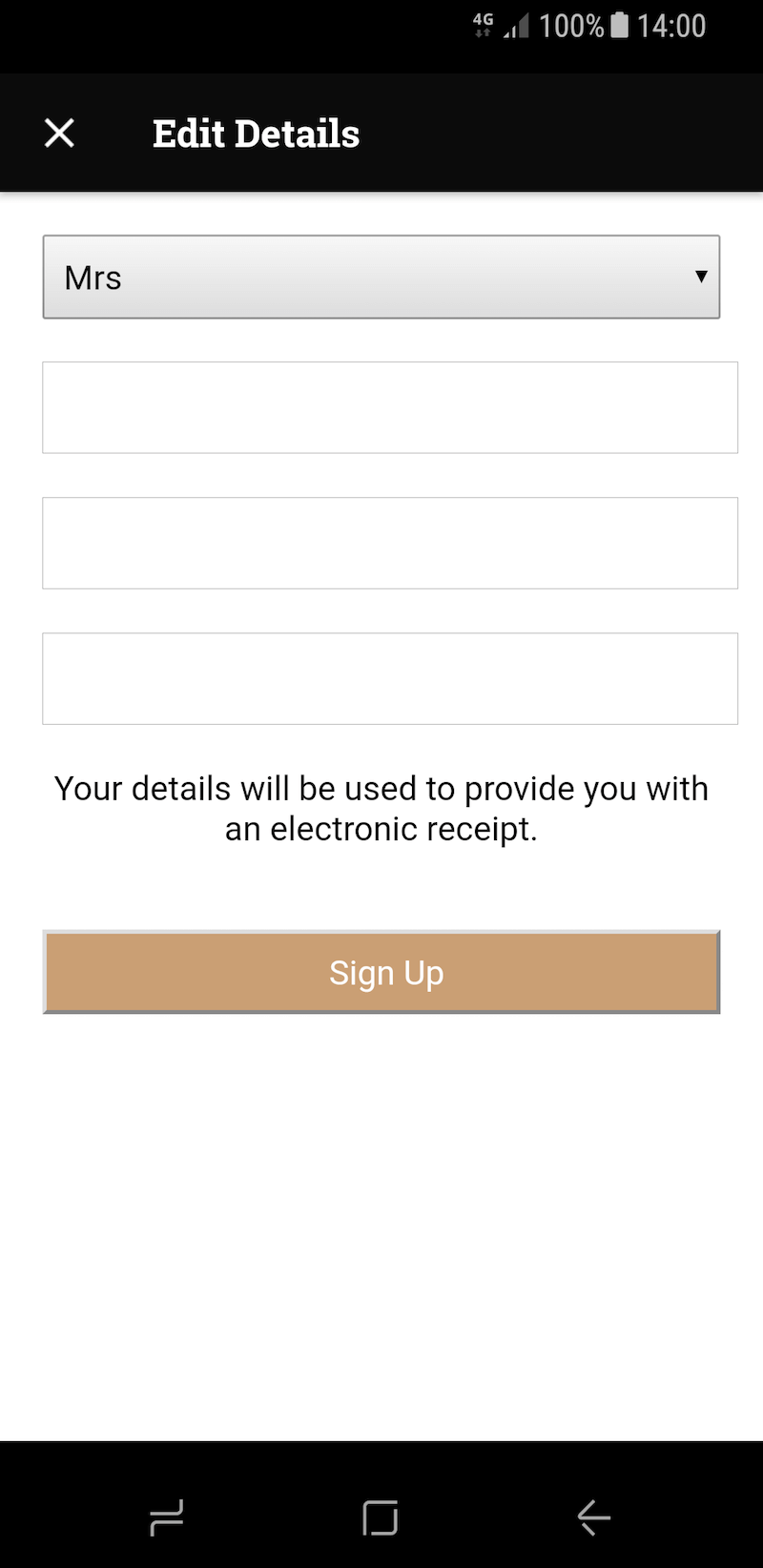

This suggestion is confirmed in the “Edit Account” option, which only allows users to edit their name and email address. This does not meet the third PbD principle “Privacy must be embedded into design.”

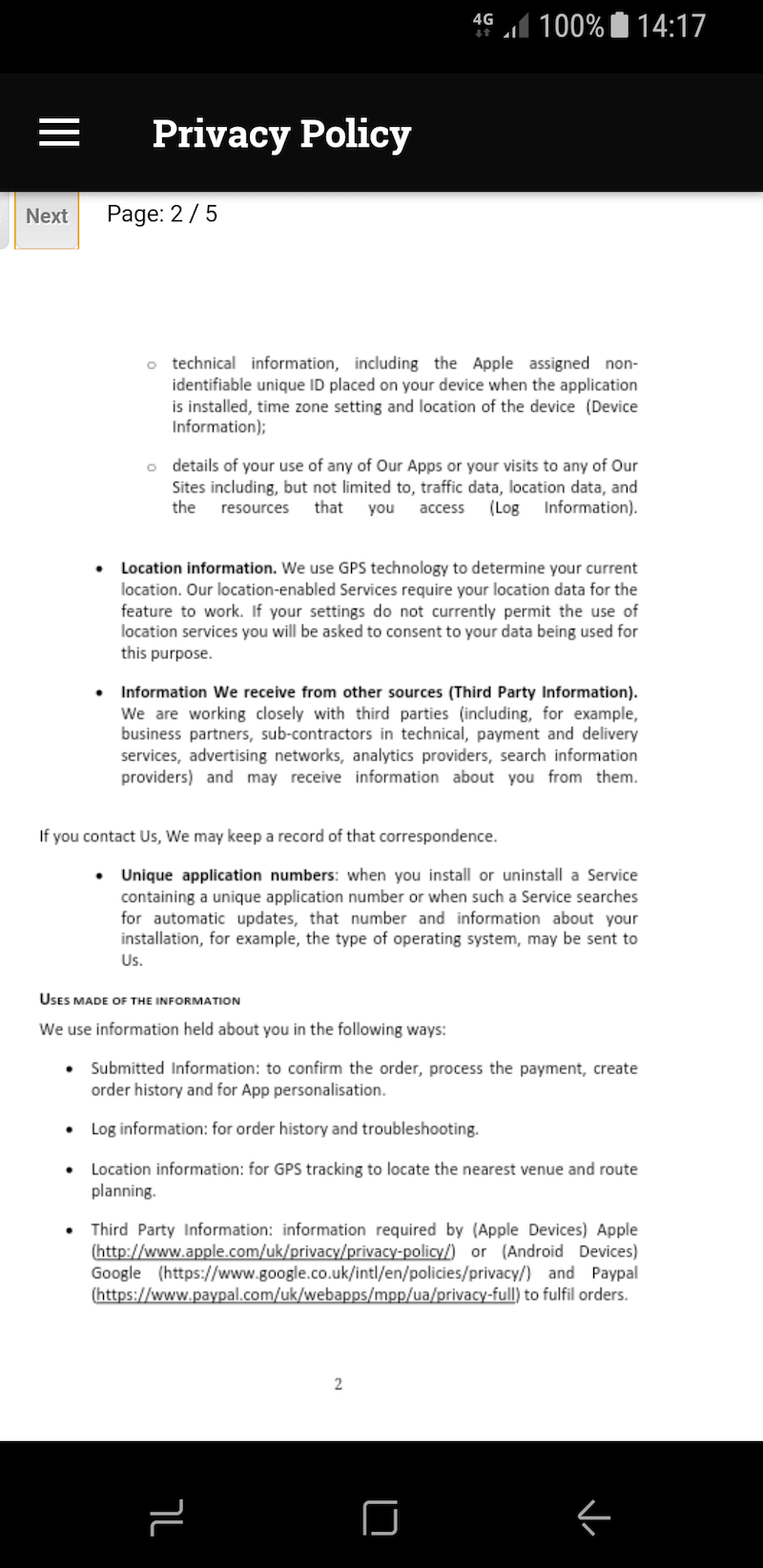

The link to the privacy policy provides a blurry scan of a five-page PDF that is written for the outdated 1995 data protection directive. There are no user controls or granular options. If I wanted to exercise control over my data, I would have to write an email to a generic customer-service address or, alternatively — in the time-honored tradition of privacy policies that are really trying to fob users off — send them a letter in the post. This does not meet the seventh PbD principle of giving users granular privacy options with maximized privacy defaults.

The privacy policy informs me that my data will be shared with third parties but gives me no indication as to who those third parties are, nor does it give me the option to withhold that data sharing. There is no distinction between third parties whose services are necessary for the transaction (for example, PayPal) and unnecessary services, such as ad networks. This does not meet the sixth PbD principle.

But let’s say I write about this stuff for a living, and so I just really need a beer. I go to the pub and fire up the Wi-Fi to use its app. When I connect to the Wi-Fi, I notice its “Settings” page. That page merely provides links to three legal documents. As with the pub’s own app, there are no settings to change, no options and no choices. There is no PbD whatsoever.

It’s clear that the only way I can ensure my privacy with this pub chain is to not use the app or its Wi-Fi at all. This creates the zero-sum dichotomy, which the fourth PbD principle seeks to avoid.

This pub chain does not meet good PbD practice, or GDPR compliance, by any definition.

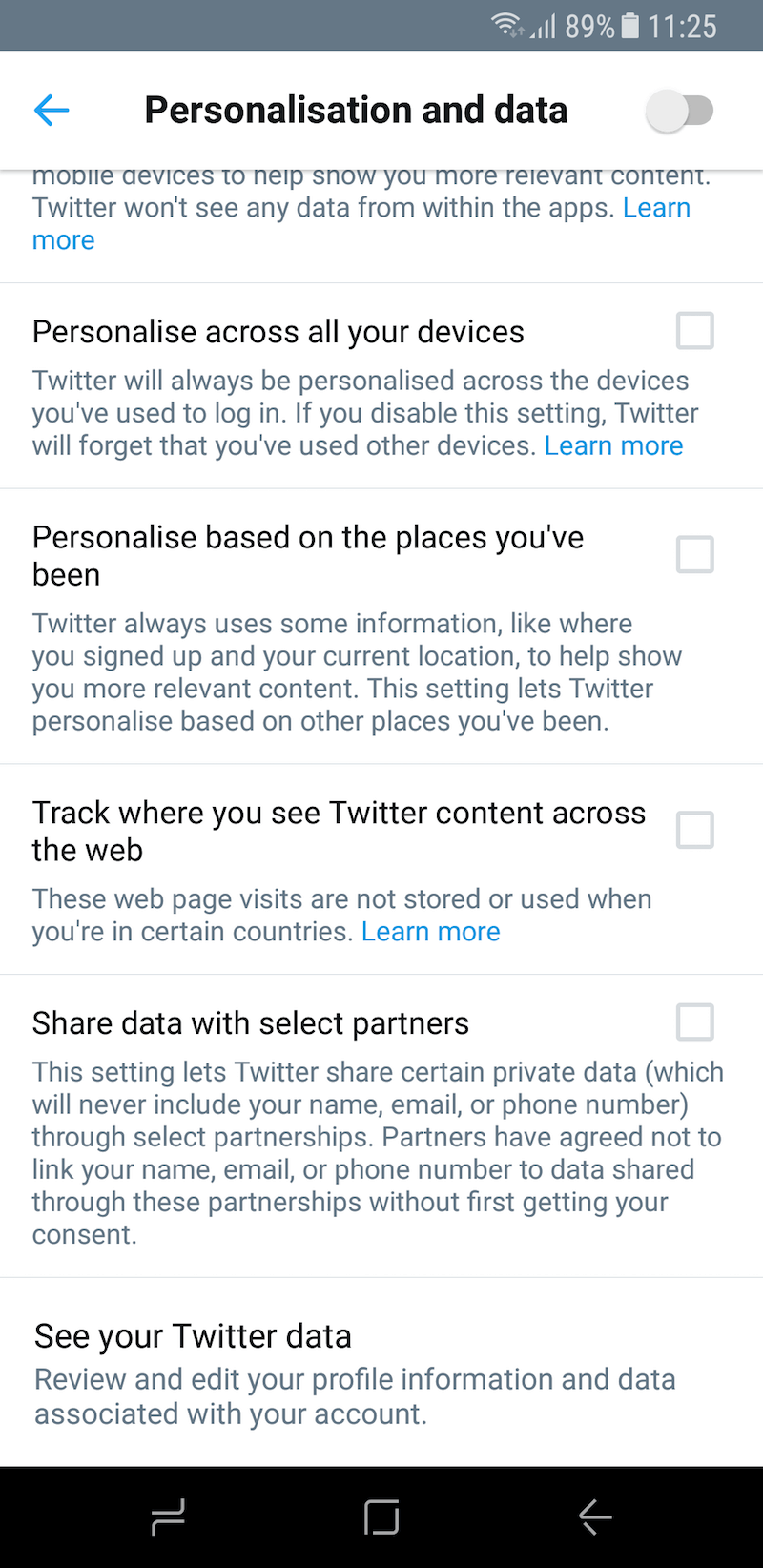

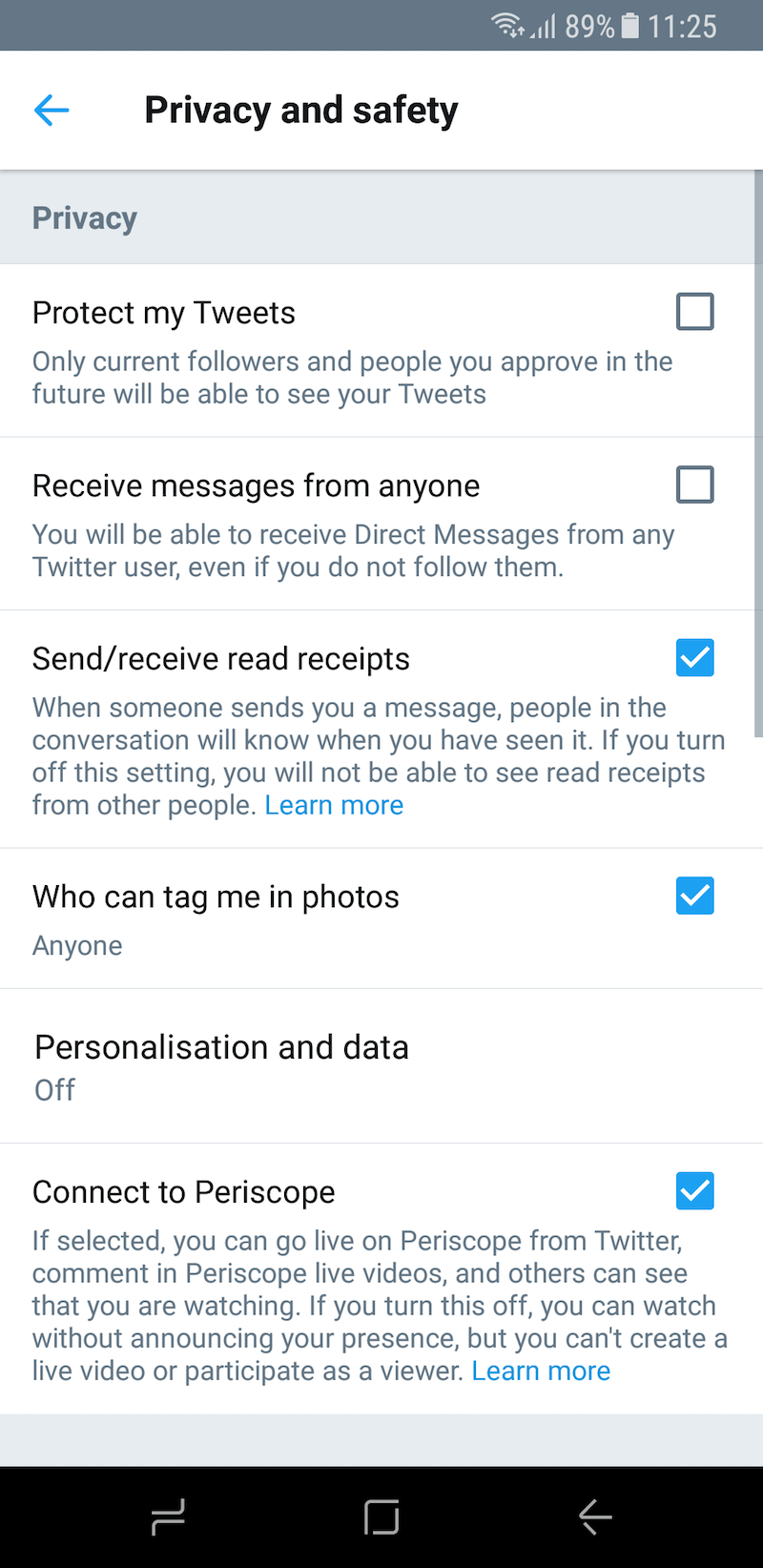

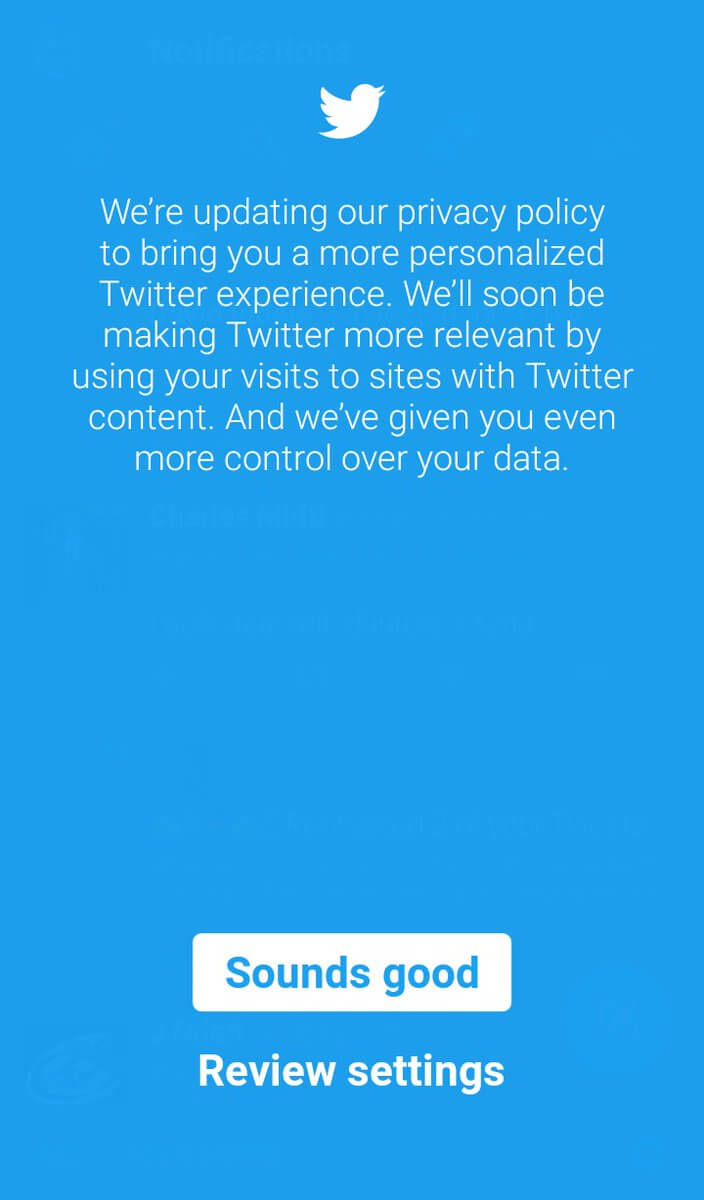

By contrast, Twitter’s recent privacy overhaul demonstrates very good PbD practice and early GDPR compliance. Here’s the catch: Its new privacy choices could have a detrimental and negative effect on users’ privacy. The difference, however, is that it has been open and transparent and has given users educated choices and options.

The privacy overhaul offers a range of granular privacy options, which are clearly communicated, including a clear notice that it may share your data with third parties. Users can disable some or all options.

A prominent splash screen drew users’ attention to the changes, increasing the likelihood that they would take the time to educate themselves on their privacy options.

Privacy Impact Assessment

A privacy impact assessment (PIA) is simply a process of documenting the issues, questions and actions required to implement a healthy PbD process in a project, service or product. PIAs are a core requirement of GDPR, and in the event of a data protection issue, your PIA will determine the shape of your engagement with a regulatory authority. You should use a PIA when starting a new project, and run a PIA evaluation of any existing ones.

The steps in a PIA are as follows:

- Identify the need for a PIA.

- Describe the information flows within a project or service (user to service provider, user to user, service provider to user, user to third parties, service provider to third parties).

- Identify the privacy- and data-protection risks.

- Identify and evaluate the privacy solutions.

- Sign off and record the PIA outcomes.

- Integrate the outcomes into the project plan.

- Consult with internal and external stakeholders as needed throughout the process.

Take some time to come up with a PIA template unique to your business or project that you can use as needed. The guidance from ICO, the UK data-protection regulator, will help you to do that.

Privacy Information Notice

Good PbD practice gives users clear information and informed choices. Privacy information notices are central to that. The days of privacy policies being pages upon pages of dense legal babble, focused on the needs of the service provider and not the user, are over.

Your app, product or service should have a privacy information notice, including the following details:

- What data are you collecting?

- Why are you collecting it, and is that reasoning legally justifiable?

- Which third parties are you sharing it with?

- What third-party data are you aggregating it with?

- Where are you getting that information from?

- How long are you keeping it?

- How can the user invoke their rights?

- Include any information regarding the use of personal data to fulfil a contract.

Many European data protection regulators are devising standardized templates for privacy information notices, and you should check with yours to follow the progress on any required format ahead of the May 2018 deadline.

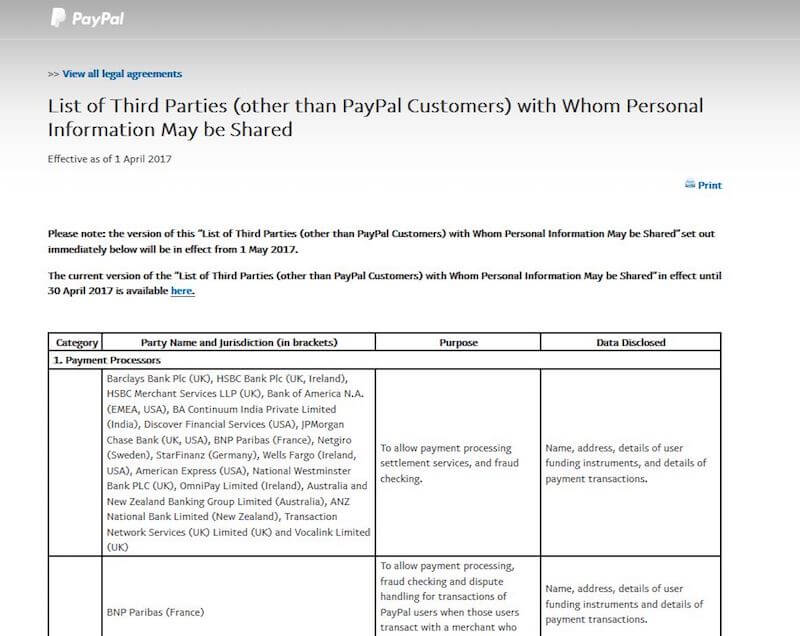

Under GDPR, the old privacy policy trick of stating “we may share your data with third parties” will no longer be considered compliant. GDPR and PbD require you to list exactly who those parties are and what they do with user data.

As one dramatic example, PayPal’s recent updated notice lists over 600 third-party service providers. The fact that PayPal shares data with up to 600 third parties is not news. That information is simply being brought into the open.

Security Measures

Good PbD compliance is not just about UX. Healthy compliance also involves implementing adequate technical and security measures to protect user data. These measures, as with other aspects of full GDPR compliance, must be documented and made accountable to a regulator on request.

PbD compliance on a technical and security level could include:

- password hashing and salting;

- data sandboxing;

- pseudonymization and anonymization;

- automated background updates;

- encryption at rest and in transit;

- responsible disclosure;

- staff training and accountability on data protection;

- physical security of servers, systems and storage.

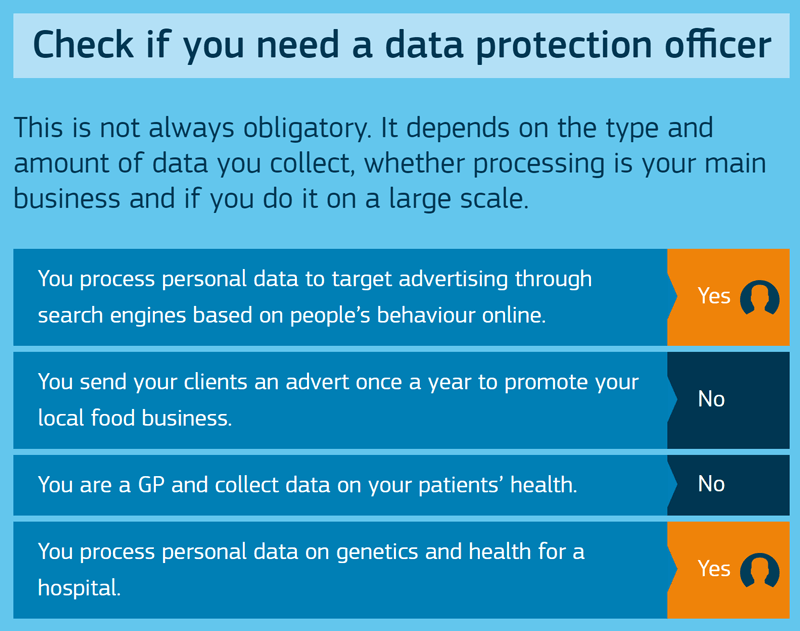

Data Protection Officer

Under GDPR, companies processing certain kinds of data must appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO), a named individual with legally accountable responsibility for an organization’s privacy compliance, including PbD. This requirement is regardless of a company’s size, which means that even the tiniest business engaged in certain kinds of data processing must appoint a DPO.

A DPO does not have to be in-house or full-time, nor are legal qualifications required. Very small businesses can appoint a DPO on an ad-hoc or outsourced basis. Check with your EU member state’s data-protection regulator for information on your national requirements for a DPO.

We would encourage all organizations to voluntarily appoint a DPO regardless of the nature of their work. Think of a DPO as the health and safety officer for privacy. Having someone act as the “good cop” to keep your development processes legally compliant — and acting as the “bad cop” if your practices are slipping — can save you from a world of troubles down the road.

Change Your Thinking

The PbD framework poses challenges that only you can answer. No one else can do it for you: it is your responsibility to commence the process. If you are within Europe, have a look at your national data-protection regulator’s GDPR and PbD resources. If you are outside Europe, we have provided some links and resources below.

Don’t view PbD as a checklist of boxes to be ticked because “the law says so,” nor think of it as something you have to do “or else.” Instead, use PbD to think really creatively. Think of all the ways that your users’ data can be misused, accessed, stolen, shared or combined. Think of where data might be located, even if you might not be aware of it. Think of what liabilities you might be creating for yourself by collecting, retaining and aggregating data that you don’t really need. Think of how the third parties you share data with, even if they are your business partners, could create liabilities for you. And in our current political climate, think about the ways that the data you collect and process could be used to do harm to your users. There are no wrong questions to ask, but there are questions that it would be wrong not to ask.

Adopting PbD into your development workflow will create new steps to follow and new obligations to meet. These steps, as onerous as they might feel, are necessary in our rapidly changing world. So, view PbD as a culture shift. Use it as an opportunity to improve your policies, practices and products by incorporating privacy into your development culture. Your users will be better protected, your business’s reputation will improve, and you will be well on the road to healthy legal compliance. In an often bewildering world, if these steps are all we can take to make a difference one app at a time, they are worth a lot.

More Information And Resources

- “Privacy by Design,” Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario An introduction.

- Conducting Privacy Impact Assessments: Code of Practice” (PDF), Information Commissioner’s Office

- Privacy in Mobile Apps: Guidance for App Developers” (PDF), Information Commissioner’s Office

- “Data Protection: Better Rules for Small Business,” European Commission Overview of the EU’s GDPR.

- “Privacy Design Guidelines for Mobile Application Development,” GSMA

Further Reading

- Privacy Guidelines For Designing Personalization

- Driving App Engagement With Personalization Techniques

- Real-Time Data And A More Personalized Web

- State Of GDPR In 2021: Cookie Consent For Designers And Developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

Register now for WAS 2026

Register now for WAS 2026 SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App