Designing For Accessibility And Inclusion

“Accessibility is solved at the design stage.” This is a phrase that Daniel Na and his team heard over and over again while attending a conference. To design for accessibility means to be inclusive to the needs of your users. This includes your target users, users outside of your target demographic, users with disabilities, and even users from different cultures and countries. Understanding those needs is the key to crafting better and more accessible experiences for them.

One of the most common problems when designing for accessibility is knowing what needs you should design for. It’s not that we intentionally design to exclude users, it’s just that “we don’t know what we don’t know.” So, when it comes to accessibility, there’s a lot to know.

How do we go about understanding the myriad of users and their needs? How can we ensure that their needs are met in our design? To answer these questions, I have found that it is helpful to apply a critical analysis technique of viewing a design through different lenses.

“Good [accessible] design happens when you view your [design] from many different perspectives, or lenses.”

— The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses

A lens is “a narrowed filter through which a topic can be considered or examined.” Often used to examine works of art, literature, or film, lenses ask us to leave behind our worldview and instead view the world through a different context.

For example, viewing art through a lens of history asks us to understand the “social, political, economic, cultural, and/or intellectual climate of the time.” This allows us to better understand what world influences affected the artist and how that shaped the artwork and its message.

Accessibility lenses are a filter that we can use to understand how different aspects of the design affect the needs of the users. Each lens presents a set of questions to ask yourself throughout the design process. By using these lenses, you will become more inclusive to the needs of your users, allowing you to design a more accessible user experience for all.

The Lenses of Accessibility are:

- Lens of Animation and Effects

- Lens of Audio and Video

- Lens of Color

- Lens of Controls

- Lens of Font

- Lens of Images and Icons

- Lens of Keyboard

- Lens of Layout

- Lens of Material Honesty

- Lens of Readability

- Lens of Structure

- Lens of Time

You should know that not every lens will apply to every design. While some can apply to every design, others are more situational. What works best in one design may not work for another.

The questions provided by each lens are merely a tool to help you understand what problems may arise. As always, you should test your design with users to ensure it’s usable and accessible to them.

Lens Of Animation And Effects

Effective animations can help bring a page and brand to life, guide the users focus, and help orient a user. But animations are a double-edged sword. Not only can misusing animations cause confusion or be distracting, but they can also be potentially deadly for some users.

Fast flashing effects (defined as flashing more than three times a second) or high-intensity effects and patterns can cause seizures, known as ‘photosensitive epilepsy.’ Photosensitivity can also cause headaches, nausea, and dizziness. Users with photosensitive epilepsy have to be very careful when using the web as they never know when something might cause a seizure.

Other effects, such as parallax or motion effects, can cause some users to feel dizzy or experience vertigo due to vestibular sensitivity. The vestibular system controls a person’s balance and sense of motion. When this system doesn’t function as it should, it causes dizziness and nausea.

“Imagine a world where your internal gyroscope is not working properly. Very similar to being intoxicated, things seem to move of their own accord, your feet never quite seem to be stable underneath you, and your senses are moving faster or slower than your body.”

— A Primer To Vestibular Disorders

Constant animations or motion can also be distracting to users, especially to users who have difficulty concentrating. GIFs are notably problematic as our eyes are drawn towards movement, making it easy to be distracted by anything that updates or moves constantly.

This isn’t to say that animation is bad and you shouldn’t use it. Instead you should understand why you’re using the animation and how to design safer animations. Generally speaking, you should try to design animations that cover small distances, match direction and speed of other moving objects (including scroll), and are relatively small to the screen size.

You should also provide controls or options to cater the experience for the user. For example, Slack lets you hide animated images or emojis as both a global setting and on a per image basis.

To use the Lens of Animation and Effects, ask yourself these questions:

- Are there any effects that could cause a seizure?

- Are there any animations or effects that could cause dizziness or vertigo through use of motion?

- Are there any animations that could be distracting by constantly moving, blinking, or auto-updating?

- Is it possible to provide controls or options to stop, pause, hide, or change the frequency of any animations or effects?

Lens Of Audio And Video

Autoplaying videos and audio can be pretty annoying. Not only do they break a users concentration, but they also force the user to hunt down the offending media and mute or stop it. As a general rule, don’t autoplay media.

“Use autoplay sparingly. Autoplay can be a powerful engagement tool, but it can also annoy users if undesired sound is played or they perceive unnecessary resource usage (e.g. data, battery) as the result of unwanted video playback.”

— Google Autoplay guidelines

You’re now probably asking, “But what if I autoplay the video in the background but keep it muted?” While using videos as backgrounds may be a growing trend in today’s web design, background videos suffer from the same problems as GIFs and constant moving animations: they can be distracting. As such, you should provide controls or options to pause or disable the video.

Along with controls, videos should have transcripts and/or subtitles so users can consume the content in a way that works best for them. Users who are visually impaired or who would rather read instead of watch the video need a transcript, while users who aren’t able to or don’t want to listen to the video need subtitles.

To use the Lens of Audio and Video, ask yourself these questions:

- Are there any audio or video that could be annoying by autoplaying?

- Is it possible to provide controls to stop, pause, or hide any audio or videos that autoplay?

- Do videos have transcripts and/or subtitles?

Lens Of Color

Color plays an important part in a design. Colors evoke emotions, feelings, and ideas. Colors can also help strengthen a brand’s message and perception. Yet the power of colors is lost when a user can’t see them or perceives them differently.

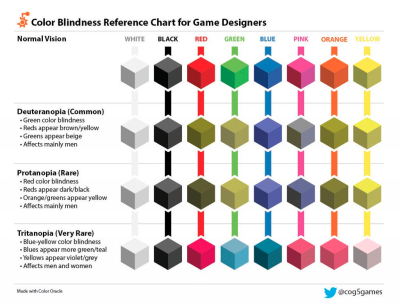

Color blindness affects roughly 1 in 12 men and 1 in 200 women. Deuteranopia (red-green color blindness) is the most common form of color blindness, affecting about 6% of men. Users with red-green color blindness typically perceive reds, greens, and oranges as yellowish.

Color meaning is also problematic for international users. Colors mean different things in different countries and cultures. In Western cultures, red is typically used to represent negative trends and green positive trends, but the opposite is true in Eastern and Asian cultures.

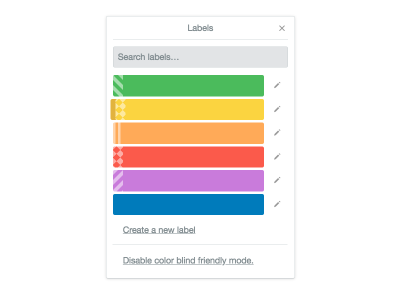

Because colors and their meanings can be lost either through cultural differences or color blindness, you should always add a non-color identifier. Identifiers such as icons or text descriptions can help bridge cultural differences while patterns work well to distinguish between colors.

Oversaturated colors, high contrasting colors, and even just the color yellow can be uncomfortable and unsettling for some users, prominently those on the autism spectrum. It’s best to avoid high concentrations of these types of colors to help users remain comfortable.

Poor contrast between foreground and background colors make it harder to see for users with low vision, using a low-end monitor, or who are just in direct sunlight. All text, icons, and any focus indicators used for users using a keyboard should meet a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 to the background color.

You should also ensure your design and colors work well in different settings of Windows High Contrast mode. A common pitfall is that text becomes invisible on certain high contrast mode backgrounds.

To use the Lens of Color, ask yourself these questions:

- If the color was removed from the design, what meaning would be lost?

- How could I provide meaning without using color?

- Are any colors oversaturated or have high contrast that could cause users to become overstimulated or uncomfortable?

- Does the foreground and background color of all text, icons, and focus indicators meet contrast ratio guidelines of 4.5:1?

Lens Of Controls

Controls, also called ‘interactive content,’ are any UI elements that the user can interact with, be they buttons, links, inputs, or any HTML element with an event listener. Controls that are too small or too close together can cause lots of problems for users.

Small controls are hard to click on for users who are unable to be accurate with a pointer, such as those with tremors, or those who suffer from reduced dexterity due to age. The default size of checkboxes and radio buttons, for example, can pose problems for older users. Even when a label is provided that could be clicked on instead, not all users know they can do so.

Controls that are too close together can cause problems for touch screen users. Fingers are big and difficult to be precise with. Accidentally touching the wrong control can cause frustration, especially if that control navigates you away or makes you lose your context.

Controls that are nested inside another control can also contribute to touch errors. Not only is it not allowed in the HTML spec, it also makes it easy to accidentally select the parent control instead of the one you wanted.

To give users enough room to accurately select a control, the recommended minimum size for a control is 34 by 34 device independent pixels, but Google recommends at least 48 by 48 pixels, while the WCAG spec recommends at least 44 by 44 pixels. This size also includes any padding the control has. So a control could visually be 24 by 24 pixels but with an additional 10 pixels of padding on all sides would bring it up to 44 by 44 pixels.

It’s also recommended that controls be placed far enough apart to reduce touch errors. Microsoft recommends at least 8 pixels of spacing while Google recommends controls be spaced at least 32 pixels apart.

Controls should also have a visible text label. Not only do screen readers require the text label to know what the control does, but it’s been shown that text labels help all users better understand a controls purpose. This is especially important for form inputs and icons.

To use the Lens of Controls, ask yourself these questions:

- Are any controls not large enough for someone to touch?

- Are any controls too close together that would make it easy to touch the wrong one?

- Are there any controls inside another control or clickable region?

- Do all controls have a visible text label?

Lens Of Font

In the early days of the web, we designed web pages with a font size between 9 and 14 pixels. This worked out just fine back then as monitors had a relatively known screen size. We designed thinking that the browser window was a constant, something that couldn’t be changed.

Technology today is very different than it was 20 years ago. Today, browsers can be used on any device of any size, from a small watch to a huge 4K screen. We can no longer use fixed font sizes to design our sites. Font sizes must be as responsive as the design itself.

Not only should the font sizes be responsive, but the design should be flexible enough to allow users to customize the font size, line height, or letter spacing to a comfortable reading level. Many users make use of custom CSS that helps them have a better reading experience.

The font itself should be easy to read. You may be wondering if one font is more readable than another. The truth of the matter is that the font doesn’t really make a difference to readability. Instead it’s the font style that plays an important role in a fonts readability.

Decorative or cursive font styles are harder to read for many users, but especially problematic for users with dyslexia. Small font sizes, italicized text, and all uppercase text are also difficult for users. Overall, larger text, shorter line lengths, taller line heights, and increased letter spacing can help all users have a better reading experience.

To use the Lens of Font, ask yourself these questions:

- Is the design flexible enough that the font could be modified to a comfortable reading level by the user?

- Is the font style easy to read?

Lens Of Images And Icons

They say, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Still, a picture you can’t see is speechless, right?

Images can be used in a design to convey a specific meaning or feeling. Other times they can be used to simplify complex ideas. Whichever the case for the image, a user who uses a screen reader needs to be told what the meaning of the image is.

As the designer, you understand best the meaning or information the image conveys. As such, you should annotate the design with this information so it’s not left out or misinterpreted later. This will be used to create the alt text for the image.

How you describe an image depends entirely on context, or how much textual information is already available that describes the information. It also depends on if the image is just for decoration, conveys meaning, or contains text.

“You almost never describe what the picture looks like, instead you explain the information the picture contains.”

— Five Golden Rules for Compliant Alt Text

Since knowing how to describe an image can be difficult, there’s a handy decision tree to help when deciding. Generally speaking, if the image is decorational or there’s surrounding text that already describes the image’s information, no further information is needed. Otherwise you should describe the information of the image. If the image contains text, repeat the text in the description as well.

Descriptions should be succinct. It’s recommended to use no more than two sentences, but aim for one concise sentence when possible. This allows users to quickly understand the image without having to listen to a lengthy description.

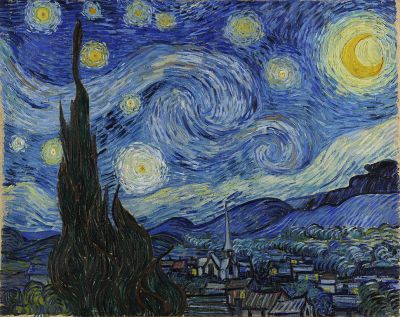

As an example, if you were to describe this image for a screen reader, what would you say?

Since we describe the information of the image and not the image itself, the description could be Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night since there is no other surrounding context that describes it. What you shouldn’t put is a description of the style of the painting or what the picture looks like.

If the information of the image would require a lengthy description, such as a complex chart, you shouldn’t put that description in the alt text. Instead, you should still use a short description for the alt text and then provide the long description as either a caption or link to a different page.

This way, users can still get the most important information quickly but have the ability to dig in further if they wish. If the image is of a chart, you should repeat the data of the chart just like you would for text in the image.

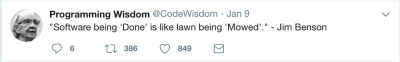

If the platform you are designing for allows users to upload images, you should provide a way for the user to enter the alt text along with the image. For example, Twitter allows its users to write alt text when they upload an image to a tweet.

To use the Lens of Images and Icons, ask yourself these questions:

- Does any image contain information that would be lost if it was not viewable?

- How could I provide the information in a non-visual way?

- If the image is controlled by the user, is it possible to provide a way for them to enter the alt text description?

Lens Of Keyboard

Keyboard accessibility is among the most important aspects of an accessible design, yet it is also among the most overlooked.

There are many reasons why a user would use a keyboard instead of a mouse. Users who use a screen reader use the keyboard to read the page. A user with tremors may use a keyboard because it provides better accuracy than a mouse. Even power users will use a keyboard because it’s faster and more efficient.

A user using a keyboard typically uses the tab key to navigate to each control in sequence. A logical order for the tab order greatly helps users know where the next key press will take them. In western cultures, this usually means from left to right, top to bottom. Unexpected tab orders results in users becoming lost and having to scan frantically for where the focus went.

Sequential tab order also means that they must tab through all controls that are before the one that they want. If that control is tens or hundreds of keystrokes away, it can be a real pain point for the user.

By making the most important user flows nearer to the top of the tab order, we can help enable our users to be more efficient and effective. However, this isn’t always possible nor practical to do. In these cases, providing a way to quickly jump to a particular flow or content can still allow them to be efficient. This is why “skip to content” links are helpful.

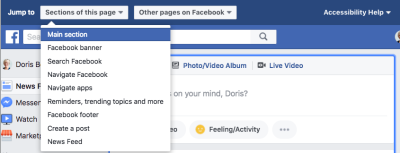

A good example of this is Facebook which provides a keyboard navigation menu that allows users to jump to specific sections of the site. This greatly speeds up the ability for a user to interact with the page and the content they want.

When tabbing through a design, focus styles should always be visible or a user can easily become lost. Just like an unexpected tab order, not having good focus indicators results in users not knowing what is currently focused and having to scan the page.

Changing the look of the default focus indicator can sometimes improve the experience for users. A good focus indicator doesn’t rely on color alone to indicate focus (Lens of Color), and should be distinct enough to easily allow the user to find it. For example, a blue focus ring around a similarly colored blue button may not be visually distinct to discern that it is focused.

Although this lens focuses on keyboard accessibility, it’s important to note that it applies to any way a user could interact with a website without a mouse. Devices such as mouth sticks, switch access buttons, sip and puff buttons, and eye tracking software all require the page to be keyboard accessible.

By improving keyboard accessibility, you allow a wide range of users better access to your site.

To use the Lens of Keyboard, ask yourself these questions:

- What keyboard navigation order makes the most sense for the design?

- How could a keyboard user get to what they want in the quickest way possible?

- Is the focus indicator always visible and visually distinct?

Lens Of Layout

Layout contributes a great deal to the usability of a site. Having a layout that is easy to follow with easy to find content makes all the difference to your users. A layout should have a meaningful and logical sequence for the user.

With the advent of CSS Grid, being able to change the layout to be more meaningful based on the available space is easier than ever. However, changing the visual layout creates problems for users who rely on the structural layout of the page.

The structural layout is what is used by screen readers and users using a keyboard. When the visual layout changes but not the underlying structural layout, these users can become confused as their tab order is no longer logical. If you must change the visual layout, you should do so by changing the structural layout so users using a keyboard maintain a sequential and logical tab order.

The layout should be resizable and flexible to a minimum of 320 pixels with no horizontal scroll bars so that it can be viewed comfortably on a phone. The layout should also be flexible enough to be zoomed in to 400% (also with no horizontal scroll bars) for users who need to increase the font size for a better reading experience.

Users using a screen magnifier benefit when related content is in close proximity to one another. A screen magnifier only provides the user with a small view of the entire layout, so content that is related but far away, or changes far away from where the interaction occurred is hard to find and can go unnoticed.

To use the Lens of Layout, ask yourself these questions:

- Does the layout have a meaningful and logical sequence?

- What should happen to the layout when it’s viewed on a small screen or zoomed in to 400%?

- Is content that is related or changes due to user interaction in close proximity to one another?

Lens Of Material Honesty

Material honesty is an architectural design value that states that a material should be honest to itself and not be used as a substitute for another material. It means that concrete should look like concrete and not be painted or sculpted to look like bricks.

Material honesty values and celebrates the unique properties and characteristics of each material. An architect who follows material honesty knows when each material should be used and how to use it without tarnishing itself.

Material honesty is not a hard and fast rule though. It lies on a continuum. Like all values, you are allowed to break them when you understand them. As the saying goes, they are “more what you’d call “guidelines” than actual rules.”

When applied to web design, material honesty means that one element or component shouldn’t look, behave, or function as if it were another element or component. Doing so would cheat the user and could lead to confusion. A common example of this are buttons that look like links or links that look like buttons.

Links and buttons have different behaviors and affordances. A link is activated with the enter key, typically takes you to a different page, and has a special context menu on right click. Buttons are activated with the space key, used primarily to trigger interactions on the current page, and have no such context menu.

When a link is styled to look like a button or vise versa, a user could become confused as it does not behave and function as it looks. If the “button” navigates the user away unexpectedly, they might become frustrated if they lost data in the process.

“At first glance everything looks fine, but it won’t stand up to scrutiny. As soon as such a website is stress‐tested by actual usage across a range of browsers, the façade crumbles.”

— Resilient Web Design

Where this becomes the most problematic is when a link and button are styled the same and are placed next to one another. As there is nothing to differentiate between the two, a user can accidentally navigate when they thought they wouldn’t.

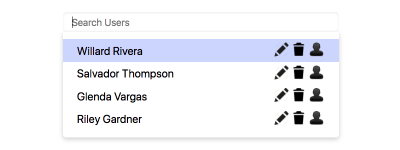

When a component behaves differently than expected, it can easily lead to problems for users using a keyboard or screen reader. An autocomplete menu that is more than an autocomplete menu is one such example.

Autocomplete is used to suggest or predict the rest of a word a user is typing. An autocomplete menu allows a user to select from a large list of options when not all options can be shown.

An autocomplete menu is typically attached to an input field and is navigated with the up and down arrow keys, keeping the focus inside the input field. When a user selects an option from the list, that option will override the text in the input field. Autocomplete menus are meant to be lists of just text.

The problem arises when an autocomplete menu starts to gain more behaviors. Not only can you select an option from the list, but you can edit it, delete it, or even expand or collapse sections. The autocomplete menu is no longer just a simple list of selectable text.

The added behaviors no longer mean you can just use the up and down arrows to select an option. Each option now has more than one action, so a user needs to be able to traverse two dimensions instead of just one. This means that a user using a keyboard could become confused on how to operate the component.

Screen readers suffer the most from this change of behavior as there is no easy way to help them understand it. A lot of work will be required to ensure the menu is accessible to a screen reader by using non-standard means. As such, it will might result in a sub-par or inaccessible experience for them.

To avoid these issues, it’s best to be honest to the user and the design. Instead of combining two distinct behaviors (an autocomplete menu and edit and delete functionality), leave them as two separate behaviors. Use an autocomplete menu to just autocomplete the name of a user, and have a different component or page to edit and delete users.

To use the Lens of Material Honesty, ask yourself these questions:

- Is the design being honest to the user?

- Are there any elements that behave, look, or function as another element?

- Are there any components that combine distinct behaviors into a single component? Does doing so make the component materially dishonest?

Lens Of Readability

Have you ever picked up a book only to get a few paragraphs or pages in and want to give up because the text was too hard to read? Hard to read content is mentally taxing and tiring.

Sentence length, paragraph length, and complexity of language all contribute to how readable the text is. Complex language can pose problems for users, especially those with cognitive disabilities or who aren’t fluent in the language.

Along with using plain and simple language, you should ensure each paragraph focuses on a single idea. A paragraph with a single idea is easier to remember and digest. The same is true of a sentence with fewer words.

Another contributor to the readability of content is the length of a line. The ideal line length is often quoted to be between 45 and 75 characters. A line that is too long causes users to lose focus and makes it harder to move to the next line correctly, while a line that is too short causes users to jump too often, causing fatigue on the eyes.

“The subconscious mind is energized when jumping to the next line. At the beginning of every new line the reader is focused, but this focus gradually wears off over the duration of the line”

— Typographie: A Manual of Design

You should also break up the content with headings, lists, or images to give mental breaks to the reader and support different learning styles. Use headings to logically group and summarize the information. Headings, links, controls, and labels should be clear and descriptive to enhance the users ability to comprehend.

To use the Lens of Readability, ask yourself these questions:

- Is the language plain and simple?

- Does each paragraph focus on a single idea?

- Are there any long paragraphs or long blocks of unbroken text?

- Are all headings, links, controls, and labels clear and descriptive?

Lens Of Structure

As mentioned in the Lens of Layout, the structural layout is what is used by screen readers and users using a keyboard. While the Lens of Layout focused on the visual layout, the Lens of Structure focuses on the structural layout, or the underlying HTML and semantics of the design.

As a designer, you may not write the structural layout of your designs. This shouldn’t stop you from thinking about how your design will ultimately be structured though. Otherwise, your design may result in an inaccessible experience for a screen reader.

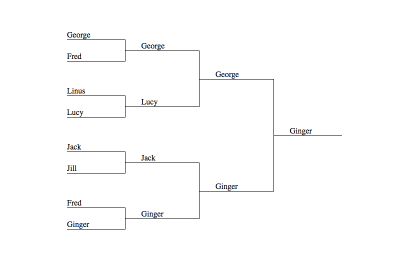

Take for example a design for a single elimination tournament bracket.

How would you know if this design was accessible to a user using a screen reader? Without understanding structure and semantics, you may not. As it stands, the design would probably result in an inaccessible experience for a user using a screen reader.

To understand why that is, we first must understand that a screen reader reads a page and its content in sequential order. This means that every name in the first column of the tournament would be read, followed by all the names in the second column, then third, then the last.

“George, Fred, Linus, Lucy, Jack, Jill, Fred, Ginger, George, Lucy, Jack, Ginger, George, Ginger, Ginger.”

If all you had was a list of seemingly random names, how would you interpret the results of the tournament? Could you say who won the tournament? Or who won game 6?

With nothing more to work with, a user using a screen reader would probably be a bit confused about the results. To be able to understand the visual design, we must provide the user with more information in the structural design.

This means that as a designer you need to know how a screen reader interacts with the HTML elements on a page so you know how to enhance their experience.

- Landmark Elements (header, nav, main, and footer)

Allow a screen reader to jump to important sections in the design. - Headings (

h1→h6)

Allow a screen reader to scan the page and get a high level overview. Screen readers can also jump to any heading. - Lists (

ulandol)

Group related items together, and allow a screen reader to easily jump from one item to another. - Buttons

Trigger interactions on the current page. - Links

Navigate or retrieve information. - Form labels

Tell screen readers what each form input is.

Knowing this, how might we provide more meaning to a user using a screen reader?

To start, we could group each column of the tournament into rounds and use headings to label each round. This way, a screen reader would understand when a new round takes place.

Next, we could help the user understand which players are playing against each other each game. We can again use headings to label each game, allowing them to find any game they might be interested in.

By just adding headings, the content would read as follows:

“__Round 1, Game 1__, George, Fred, __Game 2__, Linus, Lucy, __Game 3__, Jack, Jill, __Game 4__, Fred, Ginger, __Round 2, Game 5__, George, Lucy, __Game 6__, Jack, Ginger, __Round 3__, __Game 7__, George, Ginger, __Winner__, Ginger.”

This is already a lot more understandable than before.

The information still doesn’t answer who won a game though. To know that, you’d have to understand which game a winner plays next to see who won the previous game. For example, you’d have to know that the winner of game four plays in game six to know who advanced from game four.

We can further enhance the experience by informing the user who won each game so they don’t have to go hunting for it. Putting the text “(winner)” after the person who won the round would suffice.

We should also further group the games and rounds together using lists. Lists provide the structural semantics of the design, essentially informing the user of the connected nodes from the visual design.

If we translate this back into a visual design, the result could look as follows:

Since the headings and winner text are redundant in the visual design, you could hide them just from visual users so the end visual result looks just like the first design.

“If the end result is visually the same as where we started, why did we go through all this?” You may ask.

The reason is that you should always annotate your design with all the necessary structural design requirements needed for a better screen reader experience. This way, the person who implements the design knows to add them. If you had just handed the first design to the implementer, it would more than likely end up inaccessible.

To use the Lens of Structure, ask yourself these questions:

- Can I outline a rough HTML structure of my design?

- How can I structure the design to better help a screen reader understand the content or find the content they want?

- How can I help the person who will implement the design understand the intended structure?

Lens Of Time

Periodically in a design you may need to limit the amount of time a user can spend on a task. Sometimes it may be for security reasons, such as a session timeout. Other times it could be due to a non-functional requirement, such as a time constrained test.

Whatever the reason, you should understand that some users may need more time in order finish the task. Some users might need more time to understand the content, others might not be able to perform the task quickly, and a lot of the time they could just have been interrupted.

“The designer should assume that people will be interrupted during their activities”

— The Design of Everyday Things

Users who need more time to perform an action should be able to adjust or remove a time limit when possible. For example, with a session timeout you could alert the user when their session is about to expire and allow them to extend it.

To use the Lens of Time, ask yourself this question:

- Is it possible to provide controls to adjust or remove time limits?

Bringing It All Together

So now that you’ve learned about the different lenses of accessibility through which you can view your design, what do you do with them?

The lenses can be used at any point in the design process, even after the design has been shipped to your users. Just start with a few of them at hand, and one at a time carefully analyze the design through a lens.

Ask yourself the questions and see if anything should be adjusted to better meet the needs of a user. As you slowly make changes, bring in other lenses and repeat the process.

By looking through your design one lens at a time, you’ll be able to refine the experience to better meet users’ needs. As you are more inclusive to the needs of your users, you will create a more accessible design for all your users.

Using lenses and insightful questions to examine principles of accessibility was heavily influenced by Jesse Schell and his book “The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses.”

Further Reading

- How Accessibility Standards Can Empower Better Chart Visual Design

- A Web Designer’s Accessibility Advocacy Toolkit

- When Words Cannot Describe: Designing For AI Beyond Conversational Interfaces

- The Principles Of Visual Communication

Agent Ready is the new Headless

Agent Ready is the new Headless

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App