How To Use Storytelling In UX

As human beings, we love stories. And stories come in all shapes and sizes. Children love fairy tales; teenagers ask “and then what happened?” when their friends recount gossip; history buffs explore biographies for insight into famous personalities; science lovers enjoy documentaries that offer explanations of the world around us; and everyone likes a satisfying conclusion to a good workplace drama or romantic exploit — be it fiction or fact.

We tell stories in our day-to-day lives. In fact, according to Scientific American, 65% of the conversation is stories! They’re in commercials to grab attention, in nonfiction books to make learning more personal, and in meetings — think of how storyboards help sell management on new product features. Magazines and news shows also tell stories rather than simply listing facts to make readers and viewers care about the information.

This is why, to quote Conversion Rate Experts on websites:

“You cannot have a page that’s too long — only one that’s too boring.”

We use storytelling skills to create positive user experiences as well, though it looks a little different when a story is a part of a product. Learning how to tell a good story with a digital experience will help people care about and engage more deeply with the experience. What’s more, using the same concepts that help create a good story will help you build a better product. A good story will influence marketing material, create a product that fits into the user journey, and highlight the opportunities that need more descriptive content or a more emotional connection to the end-user.

In this article, we’ll go over five steps to building a good experience using the steps an author uses. For consistency’s sake, we’ll also look at a single product to see how their choices can be evaluated through the five steps. I’ve chosen Sanofi’s Rheumatoid Arthritis Digital Companion, an app I helped to build in 2017. This product is a beneficial example to follow because it followed best-in-class storytelling practices, and also because it is no longer available in the app store, so we can look at it at a moment in time.

But before we get into any of that… why does storytelling work?

Why Does Storytelling Work?

In “*Thinking, Fast and Slow*” (Ch. 4, The Associative Machine), psychologist Daniel Kahneman explains how our brains make sense of information:

[…] look at the following words:

Bananas Vomit

[…] There was no particular reason to do so, but your mind automatically assumed a temporal sequence and a causal connection between the words bananas and vomit forming a sketchy scenario in which bananas caused the sickness. As a result, you experience a temporary aversion to bananas (don’t worry, it will pass).

Kahneman refers to the mind “assum[ing] a temporal sequence and a causal connection” between words. Put another way, even when there is no story, the human brain makes sense of information in two ways:

- Temporal Sequence

Assuming things happen linearly, or one after another. - Causal Connection

When one thing causes another to happen.

Hubspot’s “Ultimate Guide to Storytelling” says the same thing as Kahneman, in a more readable way:

“Stories solidify abstract concepts and simplify complex messages.”

Our brains are built to find and understand stories. Therefore, it’s no wonder that a story can improve UX. UX is all about connecting an experience to a person’s mental model.

“

But writing a story is easier said than done. A story is more than just a list of things. It requires the “causal connection” that Kahneman referenced, and it must be emotionally charged in some way. Let’s review five steps that authors use which will also help you build a story into your user experience:

Step 1: Choose Your Genre

Let’s forget about UX and digital products for a moment. Just think about your favorite story. Is it a murder mystery? Is it a sitcom? A romantic comedy? It’s probably not a murdery-mystery-romantic-comedy-sitcom-movie-newspaper-article. That’s because stories have genres.

Before beginning work on a product, it’s important to identify the genre. But where an author calls it a genre, in UX we might call it a “niche” or a “use case”. This is different from an industry — it’s not enough to be creating something “for healthcare” or “for finances.” Your product “genre” is the space in which it exists and can make a difference for the target audience.

One way to determine your product’s genres is to create an elevator pitch. The team at Asana suggests that the core of an elevator pitch is the problem, solution, and value proposition.

Another way to find the “genre” of your product is to fill in the blanks:

“We want to be the _____ of __________.”

Next, write a sentence or two explaining what that means to you. The key is specificity: the second blank should specifically describe what your organization does. This is your genre.

Here’s an example:

“We want to be the Amazon of find-a-doctor apps. That means we want to be known for offering personalized recommendations.” or “We want to be the Patagonia of ticket sales. We want people to know us for not only what we sell, but the ways that we care for the environment and the world.”

When my UX team worked on Sanofi’s Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Digital Companion, we took this approach to identify what features to include, and what a “digital companion” should do for someone with RA. We knew our audience needed a simple way to manage their RA symptoms, track their medication, and exercise their joints. But they also needed to feel supported.

Thus, the genre needed to reinforce that mentality. Internally, our UX team chose to focus on being “the Mary Poppins of medication adherence apps. That means we anticipate what the patient needs, we’re generally cheerful (though, not cheesy), and we focus on what works — not what’s expected.”

Step 2: Create Context

Step two is to add context to the experience. Context is everything that surrounds us. When I use an app I use it differently if I’m sitting at home giving it my full attention than if I’m at the grocery store. The noise, the visual stimuli, and the reason I’m logging in are all context. A UX designer also creates visual context by including headers at the top of screens or breadcrumbs to show someone on a website where they are in the grand scheme of things.

In Lisa Cron’s book Story Genius, she has a section called “What Kindergarten Got (And Still Gets) Very Very Wrong.” In it, Cron explains that too many people mistake a list of things that happen for an actual story. The difference is this idea of context: a good story is not just a sentence, but a descriptive sentence: the descriptors add the context.

To give a product context, it needs to be developed with an understanding of what the background of the audience is and the context in which they’ll be using the product. For UX, some of this comes from personas. But there’s more to it than that.

In storytelling, Cron believes the problem starts in kindergarten when students are given “What ifs” like these, which are used in a school in New Jersey:

[…] The problem is, these surprises don’t lead anywhere, because they lack the essential element we were talking about earlier: context.

- What if Jane was walking along the beach and she found a bottle with a message in it? Write a story about what would happen next…

- What if Freddy woke up and discovered that there’s a castle in his backyard? He hears a strange sound coming from inside, and then…

- What if Martha walks into class and finds a great big sparkly box on her desk? She opens it and inside she finds….

[…]Because so what if Freddy discovers a castle, or Martha finds a big box on her desk or Jane finds a message in a bottle? Unless we know why these things would matter to Freddy, Martha, or Jane, they’re just a bunch of unusual things that happen, even if they do break a well-known external pattern. Not only don’t they suggest an actual story, but they also don’t suggest anything at all, other than the reaction: Wow, that’s weird!

— Lisa Cron, Story Genius

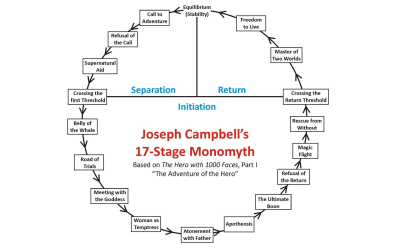

Cron suggests amending a “what if” to have a simple line providing context for the character. Joseph Campbell would call this “equilibrium” or “stability” in his well-known story structure, the Hero’s Journey (more on this in the next section). Both Campbell and Cron are saying that an author must show what stability looks like before the hero receives their call to adventure (or “what if”).

For example:

- What if Jane, who had been waiting for years to hear from her long-lost father, was walking along the beach and she found a bottle with a message in it? Write a story about what would happen next…

- What if Freddy, who dreamed of adventure in his small town, woke up and discovered that there was a castle in his backyard? He hears a strange sound coming from inside, and then…

- What if Martha, who believed she had no friends and hated school, walks into class and finds a great big sparkly box on her desk? She opens it and inside she finds…

For your product, context means going beyond the moment someone uses your product. The UX context includes the problem that someone has, what prompts them to find the product, and where they are when they use the product. Simply having a new tool or product won’t help someone to use it or feel connected to it.

Make sure to ask these questions instead:

- Who is my audience?

- Where do they spend their time?

- What were they thinking, feeling, and doing before seeing my product?

These questions will start to create a context for use. For the RA Digital Companion, we began by creating a journey map to pinpoint all the things someone with RA experiences in their daily life. We sketched out the steps of the journey map on a storyboard, focusing on moments of pain, frustration, or concern. These became the areas where we thought our app could have the most impact.

For example, we wrote the story by starting with Grace (our person with RA) waking up in the morning, her hands already hurting. We hypothesized that she reaches for her phone first thing, maybe turning off the alarm on her phone. This became an opportunity to suggest a quick “game” on her phone which would challenge her to exercise her fingers. While we might have thought of the game without the journey map or storyboard, we also might have missed this opportunity to connect to a moment in Grace’s life.

Step 3: Follow The Hero’s Journey

As exciting as a story that goes on forever might seem, ultimately it would bore the audience. A good book — and a good product — has a flow that eventually ends. The author or UX team needs to know what that flow is and how to end the experience gracefully.

In his book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell outlines 17 steps that make up a hero’s journey (a common template of storytelling). While the hero’s journey is very detailed, the overarching concept is applicable to UX design:

So, where does your story end? At what point will your product’s story reach its climax and successfully allow your end-user to be a hero? For a tax accounting software like Turbotax, the climax might be the moment that the taxes are filed. But the story isn’t over there; people need to track their refunders. Even though Turbotax doesn’t have that information in their product, they still help set expectations by creating infographics and other content that benefits their users as an “offboarding” process. In other words, where some products would leave users on their own as soon as they don’t physically need the product anymore, Turbotax offers materials to benefit users even when they’re done using the Turbotax product.

Designing for this type of offboarding is just as important as designing for onboarding. When someone uses TurboTax, they don’t want to feel harassed to come back to the app long after tax season is over. TurboTax is better off letting users stop using their product and return on their own when they need to. That’s how they keep their users happy.

When your design team identifies your offboarding point, you might try creating your user’s Hero Journey. One way to do this is to literally write a story about the user’s hero journey. Feel free to be silly, and position the user of your product as a knight in shining armor. Use the Hero’s Journey template to think about the emotional, mental, and physical state of the person using your product (remember your context from before!).

For example, let’s take a closer look at the well-known laundry detergent brand Tide and one of their commercials, “Princess Dress”:

We could break it down like this:

| Step | Observation |

|---|---|

| Call to Adventure | Lily’s princess dress getting dirty. |

| Refusal of the Call | Lily’s procrastination: she doesn’t want to change out of her princess dress. |

| Road of Trials | The father collecting the dress and giving Lily her sheriff’s costume, plus her accompanying power trip (a true trial for every parent). |

| Apotheosis | When the wash is dry and can be worn again. |

| Refusal of the Return | The parent wanting to leave everything nice and clear in the basket. |

| Crossing the Return Threshold | When Lily gets her princess dress back. |

| Master of Two Worlds | Lily is wearing clean clothes that are not yet dirty and having to be washed. |

Important note: Notice where the product is used and where the user steps away from Tide and continues on with their life.

Ideally, with an app like the Digital Companion, a user could use our app for years. But there will be ebbs and flows. Building off our storyboard we created numerous vignettes for our user “Grace”.

When Grace needs to take her injection, we knew from user research she would be worried, uncertain, and even likely to skip the medication. Instead of seeing this as a static phase in her life, we imagined her on the “Road of Trials” in the Adventure of the Hero. This imagery became a part of the language we used to encourage users to overcome their fears and bravely give themselves their injections. Over time, as the app encouraged “Grace” to build a habit of taking and recording her injections, our app copy treated her like a conquering hero, moving through the Hero’s Journey to become a “Master of Two Worlds”.

Step 4: Revise, Revise, Revise

“Good writing is good editing,” so the saying goes. The same is true with UX. For an author, finishing the story is only the first step. They then work with an editor to get more feedback and make numerous revisions. In UX, we rely on user research, and instead of “revisions,” we have iterations. Usability testing, A/B testing, user research, and prototype testing are all ways to get feedback from the target audience.

But in UX we have a major advantage. Once a book is published, the feedback can’t be acted on. But digital products can be adapted and improved even after launch. Websites get redesigns, and apps get bug fixes.

For example, when healthcare.gov launched, it immediately crashed. Harvard Business School reported:

“The key issues discussed above resulted in the rollout of the healthcare.gov website ballooning the initial $93.7M budget to an ultimate cost of $1.7B. It is easy to observe that the launch of healthcare.gov was a major failure.”

Yet healthcare.gov didn’t fail. The website still exists, and in 2021 alone more than 2.5 million people gained health coverage during the special enrollment period, allowed by the website. A failed story is simply a failure. A failed product can be iterated on.

In some cases, even a physical product can be updated to succeed. Consider a product like the Garmin watch. Even within one year there are multiple designs and styles. Some are flops, and others are major successes. The product designers learn from the flops and improve on each watch style every few years.

Although the Digital Companion is no longer available on the app store, we did have multiple releases after the initial launch. Even before that first release came out, we had ideas about how to build on the product and expand its capabilities. For example, we were able to start desirability testing on having multiple “finger stretching” game options and A/B testing video instructions for taking injections. These concepts didn’t need to wait on results from our initial release — such is the way of UX work!

Step 5: Write The Sequel

Once a product is out in the world, it’s time for the sequel. Many great stories have excellent sequels. Sometimes it’s a planned sequel like adding a new beverage to the Starbucks line. Other times it’s more of an add-on based on demand or need. A good sequel either completes a planned series or builds off the previous story. Think of these like the Star Wars trilogies versus the movies labeled “a Star Wars story.” A trilogy is a planned storyline. A one-off film may be built on the previous story and add to the world.

But some sequels do a bad job of building on the original story. Specifically, they erase characters or facts. Many Game of Thrones fans, for example, were furious with the last few episodes of the series. They saw the episodes of ignoring a key character’s growth, ignoring the rest of the series to create a nice ending.

This can happen to products as well. The tobacco industry had to find a new story for the problem their product solved after the 1964 Surgeon General’s report labeled smoking a health risk. It wasn’t the sequel they had planned, but in the words of their fictional ad man Don Draper:

“If you don’t like what people are saying, change the conversation.”

— Mad Men: Change the Conversation

As a result, they changed the product itself (adding filters to more cigarettes) as well as the advertising around it, to claim that filters were healthier and protected the smoker from tar and nicotine (they do not). And it worked!

According to an article in the medical journal BMJ Journals:

“The marketplace response was a continuation of smoking rates with a dramatic conversion from “regular” (short length, unfiltered) products to new product forms (filtered, king-sized, menthol, 100 mm).”

Each UX designer, UX writer, and engineer on the RA Digital Companion product has gone on to make our own sequels. What I learned from the RA Digital Companion — about user needs, rheumatoid arthritis, and behavior change — has played into my work, most recently at Verily. That product created a story to be shared with the end-user, but the sequels may affect health-tech as a whole.

Tell A Story And Connect

Ultimately, telling a story is how we connect to one another as humans. Whether you use Lisa Cron’s Storygenius, Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces, or simply the mindset of Daniel Kahneman, you can use storytelling to adapt your product to your user’s needs and wants.

As a Forbes article stated back in 2018:

“As human beings, we’re often drawn to the narrative; in part, because our complex psychological makeup wires us for the sharing of information through storytelling and in part due to our natural curiosity.”

Products are no exception: a good user experience takes the form of a story. The IA feels familiar and gives context and flow. The product itself will fit into a user’s sense of their own life story, and users are drawn to that.

To tell a story, you need to focus on a genre or a type of product and audience. You need to build out a world or context for your audience. Limit your scope to where you can have the most impact, revise with user feedback, and then think about the sequels. All in all, storytelling is a powerful tool for any UX designer. It will help you to create your product and understand the people who use it.

Other Resources

- How To Design Powerful Narratives On Mobile

- Once Upon A Time: Using Story Structure For Better Engagement

- The Future Of Mobile Web Design: Video Game Design And Storytelling

- Great Expectations: Using Story Principles To Anticipate What Your User Expects

- The User’s Perspective: Using Story Structure To Stand In Your User’s Shoes

Further Reading

- How To Test And Measure Content In UX

- The Human Element: Using Research And Psychology To Elevate Data Storytelling

- Make ‘Em Shine: How To Use Illustrations To Elicit Emotions

- When Friction Is A Good Thing: Designing Sustainable E-Commerce Experiences

Register Free Now

Register Free Now

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers