Fine-Grained Access Handling And Data Management With Row-Level Security

Many apps have some kind of user-specific information or data that is supposed to be accessed by a certain group of users and not by others. With these sorts of requirements comes a demand for fine-grained access handling. Whether for security or privacy reasons, dealing with sensitive data is an important topic for any app. Big or small, nobody wants to be on the wrong side of a data leakage scandal. So let’s dive in on what it means to handle sensitive or confidential information in our apps.

Take It Seriously

Regardless if you’re requesting access on Twitter, a bank, or your local library, identifying yourself is a crucial first step. Any sort of gateway needs a reliable way to verify if an access request is legitimate.

“Identity theft is not a joke.”

— Dwight Schrute

On the web, we encapsulate the process for identifying a user and granting them access as Auth, which stands for two related but distinct actions:

- Authentication: the act of confirming a user’s identity.

- Authorization: granting an authenticated user access to a resource.

It is possible to have authentication without authorization, but not the other way around. The strategy to implement authorization at a data management level can be loosely referred to as Row-Level Security (RLS), but RLS is actually a bit more than this. In this article, we will take a step deeper into managing sensitive user data and defining access roles to a user base.

Row-Level Security (RLS)

A ‘row’, in this case, refers to an entry in a database table. For example, in a posts table, a row would be a single article, check this json representation:

{

"posts": [

{

"id": "article_23495044",

"title": "User Data Management",

"content": "<huge blob of text>",

"publishedAt": "2023-03-28",

"author": "author_2929292"

},

// ...

]

}

To understand RLS, each object inside posts is a ‘row’.

The above data is enough for creating a filter algorithm to effectively enforce row-level security. Nonetheless, it’s crucial for scalability and data handling that such relationship is defined on your data layer. This way, any service that connects to your database will have all the required information to implement its own access-control logic as required. So for the above example, the schema for the posts table would roughly look like the following:

{

"posts": {

"columns": [

{

"name": "id",

"type": "string"

},

// ... other primitive types

// establish relationship with "authors"

{

"name": "author",

"type": "link",

"link": "authors"

}

]

}

}

In the above example, we define the type of each value in our posts database and establish a relationship to the authors table. So each post will receive the id of one author. This is a one-to-many relationship: one author can have many posts.

Of course, there are patterns to define many-to-many relationships as well. Take, for example, a team’s backlog. You may want only members of a certain team to have access. In such case, you can create a list of users with access to a specific resource (and thus being very granular about it), or you can define a table for team, and thus connecting a team to multiple tasks, and a team to multiple users: this pattern is called a junction table and is great for defining scoped access within your data layer.

Now we understand what authorization is and looks like in a few cases. This should be enough to design a mental model for defining access to our data. We understand that in order to use the granular access to our data effectively, our app must be aware of which user is using that particular instance of the app (aka who’s behind the mouse).

Authentication

It is time to set up a reliable and cost-effective authentication. Cost-effective because it is counter-productive to re-authenticate the user on every request. And it increases the risk factor of attacks, so let’s keep auth requests to a minimum. The way our app stores the user credentials to re-use in a defined lifecycle is called a session.

There are multiple ways of authenticating users and handling sessions. I invite you to check Eric Burel’s article on “Authentication in Websites: A Banking Analogy”. It’s a great and thorough explanation of how authentication works.

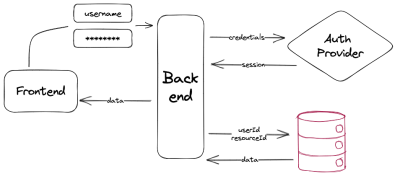

From this moment on, let’s assume we did our due diligence: username and password are securely stored, an authentication provider is able to reliably verify our user’s identity and returns a session, which is an object carrying a userId matching our user’s row in the database.

Connecting The Dots

So now that we have established what it means and the requirements each moving piece brings in order to get it working, our goal is the following:

- Authentication

The provider performs user authentication, the library creates asession, and the app receives that as apayloadfrom the auth request. - Resource request

Authenticated User performs request withresourceId; the app takesuserIdfromsession. - Granting access

It filters all resources from the table to only the ones owned byuserIdand returns (if it exists) the one withresourceId.

With the above mental model defined, it is possible to any sort of implementation and properly design your queries. For example, on our first defined schema (posts and authors), we can use filters on our fetching service to only provide access to the results a user should have:

async function getPostsByAuthor(authorId: string) {

return sdk.db.posts

.filter({

author: authorId

})

.getPaginated()

}

This contrived snippet is just to exemplify a bare-bones RLS implementation. Maybe as a food-for-thought so you can build upon it.

Conclusion

Hopefully, these concepts have offered extra clarity on defining access management to private and/or sensitive data. It’s important to note that there are security concerns before and around storing such kind of data which were beyond the scope of this article. As a general rule: store as little as you need and provide only the necessary amount of access to data. The least sensible data going over the wire or being stored by your app, the lesser the chance your app is a target or victim of attacks or leaks.

Let me know your questions or feedback in the comment section or on Twitter.

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers