Learning to Love HTML5

From my own vantage point — aside from a few disputes about what the term “HTML5” should and shouldn’t mean — the web design and development community has for the most part embraced all the new technologies and semantics with a positive attitude.

While it’s certainly true that HTML5 has the potential to change the web for the better, the reality is that these kinds of major changes can be difficult to grasp and embrace. I’m personally in the process of gaining a better understanding of the subtleties of HTML5’s various new features, so I thought I would discuss some things associated with HTML5 that appear to be somewhat confusing, and maybe this will help us all understand certain aspects of the language a little better, enabling us to use the new features in the most practical and appropriate manner possible.

The Good (and Easy) Parts

The good stuff in HTML5 has been discussed pretty solidly in a number of sources including books by Bruce Lawson, Jeremy Keith, and Mark Pilgrim, to name a few. The benefits gained from using HTML5 include improved semantics, reduced redundancies, and inclusion of new features that minimize the need for complex scripting to achieve standard tasks (like input validation in forms, for example).

I think those are all commendable improvements in the evolution of the web’s markup language. Some of the improvements, however, are a little confusing, and do seem to be a bit revolutionary, as opposed to evolutionary, the latter of which is one of the design principles on which HTML5 is based. Let’s look at a few examples, so we can see how flexible and valuable some of the new elements really are — once we get past some of the confusion.

AnIsn’t Just an Article

Among the additions to the semantic elements are the new <section> and <article> tags, which will replace certain instances of semantically meaningless <div> tags that we’re all accustomed to in XHTML. The problem arises when we try to decipher how these tags should be used.

Someone new to the language would probably assume that an <article> element would represent a single article like a blog post. But this is not always the case.

Let’s consider a blog post as an example, which is the same example used in the spec. Naturally, we would think a blog post marked up in HTML5 would look something like this:

<article>

<h1>Title of Post</h1>

<p>Content of post...</p>

<p>Content of post...</p>

</article>

<section>

<section>

<p>Comment by: Comment Author</p>

<p>Comment #1 goes here...</p>

</section> <section> <p>Comment by: Comment Author</p>

<p>Comment #2 goes here...</p>

</section> <section> <p>Comment by: Comment Author</p>

<p>Comment #3 goes here...</p>

</section>

</section>For brevity, I’ve left out some of the other HTML5 tags that might go into such an example. In this example, the <article> tags wrap the entire article, then the “section” below it wraps all the comments, each of which is in its own “section” element.

It would not be invalid or wrong to structure a blog post like this. But according to the way <article> is described in the spec, the <article> element should wrap the entire article and the comments. Additionally, each comment itself could be wrapped in <article> tags that are nested within the main <article> tag.

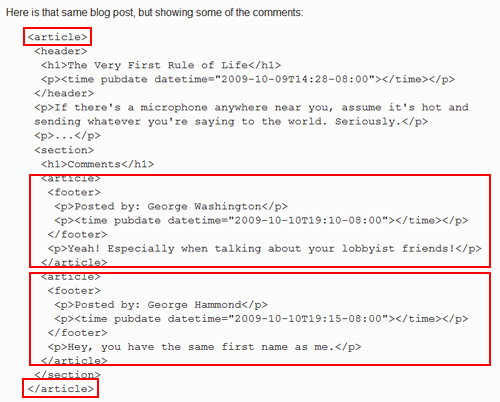

Below is a screen grab from the spec, with <article> tags indicated:

Article tags can be nested inside article tags — a concept that seems confusing at first glance.

So, an <article> element can have other <article> elements nested inside it, thus complicating how we naturally view the word “article”. Bruce Lawson, co-author of Introducing HTML5, attempts to clear up the confusion in this interview:

"Think of `

` not in terms of print, like "newspaper article" but as a discrete entity like "article of clothing" that is complete in itself, but can also mix with other articles to make a wider ensemble." — Bruce Lawson

So keep in mind that you can nest <article> elements and an <article> element can contain more than just article content. Bruce’s explanation above is very good and is the kind of HTML5 education that’s needed to help us understand how these new elements can be used.

Section or Article?

Probably one of the most confusing things to figure out when creating an HTML5 layout is whether or not to use <article> or <section>. As I write this sentence, I can honestly say I don’t know the difference without actually looking up what the spec says or referencing one of my HTML5 books. But slowly it’s becoming more clear. I think Jeremy Keith defines <article> best on page 67 of HTML5 for Web Designers:

"The

articleelement is [a] specialized kind ofsection. Use it for self-contained related content... Ask yourself if you would syndicate the content in an RSS or Atom feed. If the content still makes sense in that context, thenarticleis probably the right element to use."— Jeremy Keith, HTML5 for Web Designers

Keith’s explanation helps a lot, but then he goes on to explain that the difference between <article> and <section> is quite small, and it’s up to each developer to decide how these elements should be used. And adding to the confusion is the fact that you can have multiple articles within sections and multiple sections within articles.

As a result, you might wonder why we have both. The main difference is that the <article> element is designed for syndication, whereas the <section> element is designed for document structure and portability. This simple way to view the differences certainly helps make the two new elements a little more distinct. The important thing to keep in mind here is that, despite our initial confusion, these changes, when more widely adopted, are going to help developers and content creators to improve the way they work and the way content is shared.

Headers and Footers (Plural!)

Two other elements introduced in HTML5 are the <header> and <footer> elements. On the surface, these seem pretty straightforward. For years we’ve marking up our website headers and footers with <div id="header">, <div id="footer"> or similar. This is great for DOM manipulation and styling, because we can target these elements directly. But they mean nothing semantically.

"The

divelement has no defined semantics, and theidattribute has no defined semantics. (User agents are not allowed to infer any meaning from the value of theidattribute.)"

HTML5’s introduction of <header> and <footer> elements is the perfect way to remedy this problem of semantics, especially for such often-used elements. But these elements are not as straightforward as they seem. Technically speaking, if every website in the world added one <header> and one <footer> to each of their pages, this would be perfectly valid HTML5. But these new elements are not just limited to use as a “website header” and “website footer”.

A header is designed to mark up introductory or navigational aids, and a footer is designed to contain information about the containing element. For example, if you used the footer element as the footer for a full web page, then in that case copyright, policy links, and related content might be appropriate for it to hold. A header on the same page might contain a logo and navigation bar.

But the same page might also include multiple <section> elements. Each of those sections is permitted to contain its own header and/or footer element. Keith sums up the purpose of these elements well:

"A

headerwill usually appear at the top of a document or section, but it doesn't have to. It is defined by its content... rather than its position.""Like the

headerelement,footersounds like it's a description of position, but as withheader, this isn't the case."— Jeremy Keith, HTML5 for Web Designers

And the spec adds to Keith’s clarification by noting:

"The header element is not sectioning content; it doesn't introduce a new section." — The header element in the HTML5 specification

These explanations help dispel any false assumptions we might have about these new elements, so we can understand how these elements can be used. Really, this method of dividing pages into portable and syndicatible content is just adding semantics to what content creators and developers have been doing for years.

Headings Down A Different Path

Prior to HTML5, heading tags (<h1> through <h6>) were pretty easy to understand. Over the years, some best practices have been adopted in order to improve semantics, SEO, and accessibility. Generally, we’ve become accustomed to including a single <h1> element on each page, with the other heading elements following sequentially without gaps (although sometimes it would be necessary to reverse the order).

With the introduction of HTML5, to use the new structural elements we need to rethink the way we view the structure of our pages.

Here are some things to note about the changes in heading/document structure in HTML5

- Instead of a single

<h1>element per page, HTML5 best practice encourages up to one<h1>for each<section>element (or other section defined by some other means) - Although we’re permitted to start a section with an

<h2>(or lower-ranked) element, it’s strongly encouraged to start each<section>with an<h1>element to help sections become portable - Document nodes are created by sections, not headings (unlike previous versions of HTML)

- An

<hgroup>element is used to group related heading elements that you want to act as a single heading for a defined or implied section;<hgroup>is not used on every set of headings, only those that act as a single unit outside of adjacent content - To see if you’re structuring your document correctly, you can use the HTML5 Outliner

- Despite the above points, whatever heading/document structure you used in HTML4 or XHTML will still be valid HTML5

So, although the old way we structure pages does not amount to invalid HTML5, our view of what constitutes “best practice” document structure is changing for the better.

Block or Inline? Neither! (Sort of…)

For layout and styling purposes, CSS developers are accustomed to HTML elements (for styling and layout purposes) being defined under one of two categories: Block elements and inline elements (although you could divide those two into further categories). This understanding simplified our expectations of an element’s display on any given page, making it easier (once we grasp the difference between the two) to style and manoeuvre the elements.

HTML5 evolves this concept to include multiple categories, none of which is block or inline. Well, theoretically, block and inline elements still exist, but they do so under different labels. Now the different categories of elements include:

- Grouping Content

- Text-Level Semantics

- Sectioning Content

- Form Elements

- Embedded Content

I certainly welcome this kind of improvement to more appropriately categorize elements, and I think developers will adapt well to these changes, but it is important that we promote proper nomenclature to ensure minimal confusion over how these elements will display by default. Of all the areas discussed in this article, however, I think this one is the easiest to grasp and accept.

Conclusion

While this summarizes some of what I’ve learned in my study of HTML5, a far better way for anyone to learn about these new features to the markup is to pick up a book on the topic. I highly recommend one of those mentioned in the article, or you can read Mark Pilgrim’s book online.

These new elements and concepts don’t have to be confusing. We can take the time to study them carefully, avoiding confusion and dispelling myths. This will help us enjoy the benefits of these new elements as soon as possible, and will help developers and content creators pave the way towards a more meaningful web — a web that, to paraphrase Jeremy Keith, ‘wouldn’t exist without markup’.

Related Posts

You may be interested in the following related posts:

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding. Enterprise UX Masterclass, with Marko Dugonjic

Enterprise UX Masterclass, with Marko Dugonjic

Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!