The Story Of Scandinavian Design: Combining Function and Aesthetics

This article was written by Katrín Eyþórsdóttir, our talented and hard-working trainee from Iceland. As a designer with background in product design, Katrín is presenting her understanding of what has influenced the works of designers from Sweden, Norway and other North-European counties as well as the key attributes that these works possess.

For a long time, art has been heavily influenced by the social and political landscape. Searching through history, we find that while the social views of a certain period may no longer be relevant, the art and design of that time often are. Designers today constantly draw inspiration from history, consciously and unconsciously. Being aware of that history and knowing what has come before in your field can help you better convey the meaning in your work and forge deeper connections to your environment (artistic, social, political, etc.).

Looking back to the beginning of the 20th century and the styles and movements that ruled the art world at that time, we will look for influences and ideas that have evolved into what has been known since the mid-20th century as “Scandinavian design”. This article also offers some thoughts on how to incorporate its principles in your work today.

While the countries of Scandinavia have extreme differences, they do have some common cultural, geophysical and historical threads. Without implying that certain principles apply to all art and design in this area, this article gives an overview of the influences and state of art and design in the Nordic countries.

Historical Context

Modernism, a cultural movement that started at the end of the 19th century, was a break from the Realism that dominated the art world before. Realism’s source was the invention of the photograph and the artist’s desire to produce work that looked “real.” It was, hence, fairly conservative, and the art created in that movement was intended to be truthful and accurate. Modernism was an escape from this rigidity, and a multitude of cultural and aesthetic movements grew from it.

Shortly after 1880, William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement, inspired by the social theories of John Ruskin, began expressing their distaste for the Industrial Revolution’s machine-made designs. They denounced the uniform and monotonous products that the machine stood for, and they revitalized traditional methods of manufacturing; in the textile arts, for example. Defending and praising nature in art, human creativity and faithfulness to traditional materials, they upheld Romanticism and folk tradition in all manner of crafts.

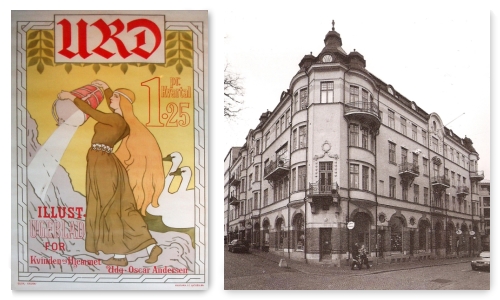

Art Nouveau, also known as “Jugendstil,” was the first widely popular art movement of the 20th century. It was conceived as a “new style for a new century.” With a focus on decorative and applied arts, the movement was a conscious resistance to the ruling art and design institutions of the era.

Dating roughly from 1880 to 1910, Art Nouveau marked the beginning of Modernism and took nature as its inspiration. The use of decorative elements in domestic settings could even be viewed as metaphors for the status of the individual in society, and they made it evident that people were eager to break away from forms and set rules. More obvious social commentary was starting to emerge in art.

Fluid shapes were used in all manner of work, be it architecture, furniture, textiles, painting or print. The style was widely celebrated as a break from the past, incorporating new and exotic materials from foreign countries, and with so-called “Japonisme” becoming popular in Western circles.

In Denmark, Skønvirke magazine started publishing in 1914. Its content was inspired by old Danish handicrafts and national Romanticism, with international influences appearing in decorations. The word “Skønvirke” became synonymous with Art Nouveau and Jugend. The delicate nature-inspired forms, graceful lines and colors fit the Scandinavian aesthetic well.

These were highly volatile times in Europe, partly because of the First World War and the growing unease with the social order. In art, everything became revolutionary instead of evolutionary, a reaction to the upheaval of war. Prior social forms and arrangements were seen as hindering civil progress, and the artist became a social and political activist. The goal was provocation, upheaval and a break from old systems. Many art movements stemmed from these broad social changes.

The machine age was drastically changing living conditions, and the seeming futility and catastrophic loss of life from the First World War raised questions about the state of human morality. The world was changing, and this change was manifested in cinema, exhibitions, books and buildings for the public to soak up.

Scandinavia Early On

Scandinavia here means the countries of Northern Europe: Denmark, Sweden, Norway. Design from there is described by many as being fairly minimalist, with clean simple lines. Highly functional, the style is effective without needing heavy elements; only what is needed is used. Survival in the north required products to be functional, and this was the basis of all design from early on.

The subtle decorative qualities stemming from the early-20th century art movements and the simple lines deriving from the inter-war art movements gave this style its elegance. The concept of “beautiful things that make your life better” was highly regarded. Scandinavian design is often referred to as democratic design, because of its aim to appeal to the masses through products that are accessible and affordable.

This ideology comes from local institutions, such as the long-established Swedish Society of Industrial Design. The goal of this association was to promote design that the general public could access and enjoy. Such goals were greatly affected by social changes taking place in Europe at the time. Even though the designs were democratic and meant for the masses, they were not stripped of all beauty in order to make them as easy to use as possible; an inspiring thought. The importance of this balance was identified by Scandinavians early on and has been maintained ever since.

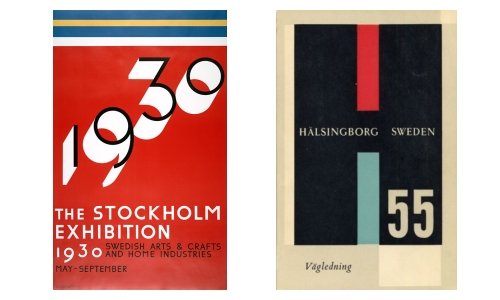

Several exhibitions of Scandinavian design were held throughout Europe and North America. One of the earliest was the Stockholm Exhibition in 1930, where functionalism blossomed and artists and companies showcased their latest products. And concurrent with an official visit by the Danish Royal couple in 1960, the Arts of Denmark Exhibition was held at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Arts.

The term “Scandinavian design” originates from a design show that traveled the US and Canada under that name from 1954 to 1957. Promoting the “Scandinavian way of living,” it exhibited various works by Nordic designers and established the meaning of the term that continues to today: beautiful, simple, clean designs, inspired by nature and the northern climate, accessible and available to all, with an emphasis on enjoying the domestic environment.

Exhibitions like these played a big role in spreading the word about Scandinavian design and in influencing the development of modernism in North America and Europe in many ways. The aesthetic had been evolving for decades by that time and was strongly influenced by art and design in Europe. It combined the trends that had emerged around the turn of the century, the clean forms that followed, as well as existing traditions in Scandinavia.

Social Consciousness In Art Movements

From about 1916 onwards, more political and social art groups became prominent in the European art world. The centuries-old establishments, academies and guilds had a long history of being steered by the ruling bourgeois. They were deeply interested in maintaining the social order, and the art that they created and commissioned reflected that. Holding on to old methods in painting and afraid of the turmoil represented by new movements, the establishment favored work that didn’t disrupt the status quo. The new movements viewed their work as being stagnant and as holding back the progress of the arts. These new movements celebrated the machine and embraced manufacturing technologies in the creation of art. Among these were the Constructivists in Russia, the Futurists in Italy, De Stijl in the Netherlands, Bauhaus in Germany and the Dadaists in Switzerland.

The Constructivist movement viewed art as part of the social structure and used it as tool to communicate political and social messages. Some of the movement’s most famous artists were Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky (who later taught at Bauhaus) and the Stenberg brothers, Georgii and Vladimir, names still well known among graphic designers today. Participating heavily in public events and partially supported by the ruling political parties, they celebrated new technologies and machine art.

De Stijl was a Dutch art movement in which Piet Mondrian and Gerrit Rietveld were among the principal members. De Stijl emphasized pure abstraction and the reduction of everything to the essentials of form and color. Everything was simplified to vertical and horizontal lines and primary colors. Unlike many contemporary movements, De Stijl was a collective project, not a political or social movement.

Bauhaus was a school in Germany that was famous for combining fine arts, crafts and technology; industrial and product design were highly regarded. The “Foundation Year” of many of today’s art and design schools has its origins here. It’s also where the field of modern furniture design started to take shape.

Highly influential, even today, the school’s three directors, Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, spread their ideas when they left Germany before and during the Second World War. Ending up in various countries, they and many of the people who taught and studied at Bauhaus left behind a body of knowledge that many of today’s designers refer to in their work, often unknowingly.

The functionalism that Bauhaus espoused was prevalent in Scandinavian architecture. The Nordic countries adopted many styles for their buildings and came up with their own, but “funkis” (the term for functionalism there) become one of the more popular styles.

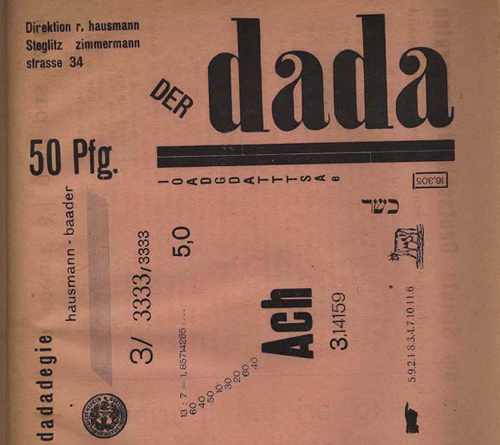

Dadaism was a fairly short-lived cultural movement that started in Switzerland shortly after World War I. But Dadaist methods and views were adopted by many and live on. Focused on ridiculing the meaninglessness of the modern world, their work encompassed literature, visual arts and theater.

With Dadaism, abstract art started to find its footing, as well as performance art and what later evolved into Pop Art. Similar to Cubists, Dadaists made use of collage, assemblage and existing products to create new pieces. Against war, against the bourgeoisie and resembling an anarchist movement, Dadaists were active around the world, holding public demonstrations and publishing journals. Dadaism gradually mixed with surrealism and other cultural and artistic movements.

In Italy, Futurism was an artistically and socially active movement that used all media, from film to food, to get its messages across. Futurism was an ideology that wanted nothing to do with the past; its proponents objected to what they regarded as stale thinking on the part of their contemporaries. Not having a distinct style of their own, they adopted the techniques of Cubism, which was the avant-garde art movement headed by Pablo Picasso, among others.

Cubism radically changed approaches in European painting and sculpture, and its effects are still evident today.

Surrealism surged in popularity around 1920, and while many Scandinavian designers and artists were heavily influenced by the movement and incorporated it into their creations, Surrealism wasn’t greeted with wide open arms. Wilhelm Bjerke-Petersen, Rita Kernn-Larsen and Olav Stromme all dabbled in surrealism at one time or another.

The following is from a review of the exhibition “Anxiety and Desire: Surrealism in Scandinavia 1930–1950.” The author, Ausra Larbey, explains how social views within Nordic countries affected the popularity and acceptance of art movements:

Ironically, their revolutionary perspective found little understanding in workers’ environment. One saw Surrealism as expression of bourgeois individualism, dealing exclusively with intellectual problems of overclass. It was perceived as an immoral and egoistic form of art, self-absorbed and decadent. The rejection was so strong that artists moved away from abstract surrealism towards more naturalistic figurative style, and later in interviews denied they ever were Surrealists.

Many of the artists in these different movements knew each other and worked together, setting up exhibitions and publishing magazines. Many of these movements were highly political and advocated for social change through art. This influenced the Scandinavian art world and helped to shape the social changes that were taking place there.

Scandinavia

The styles and movements brewing in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century spread around the world. While they didn’t espouse the same message, they all contributed to the establishment of new forms and functions.

Modernism’s scope was far and wide and developed differently in each country. The ideology spread throughout Scandinavia, with designers and artists interacting with their contemporaries throughout Europe, aided by fast-developing media such as film. In Scandinavia, the ideas gradually evolved into design principles and philosophies that eventually had international effects.

Scandinavian designers were influenced by everything going on around them. With their tradition of craftsmanship and efficient use of limited material resources (due to their relative geographic isolation), they combined the best of both worlds. In line with prevailing democratic social views, everything was made to be available to everyone. The notion of enjoying the work you do was highly regarded, and the idea that beautiful things could enrich people’s lives was kept alive.

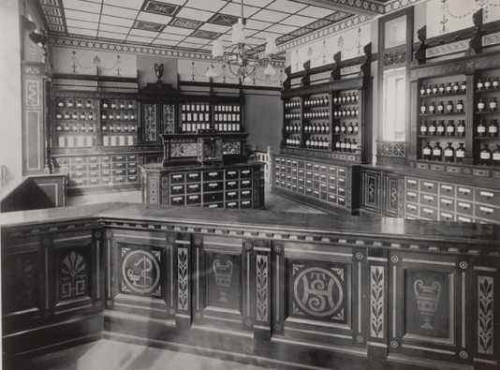

As mentioned, the Swedish Society of Industrial Design was established in 1845 to uphold and raise the high standards in various crafts-related professions. The fact that industrialization took place in Scandinavia later than in neighboring countries helped to preserve the handicraft tradition there.

Early in the 20th century, with more and more people moving from the countryside to cities, the Society broadened its scope and committed to raising standards of design in everyday life. The quest to make objects of high aesthetic quality available to the masses began in earnest during the 1920s and ’30s. Beauty, humanism and democratic ideals were the order of the day.

Mass machine production did not dominate Scandinavia as much in the years between the two World Wars as it did in the US. The scale of the industry was much smaller, and after World War II more Scandinavian countries established institutions and schools to preserve the craft traditions. Processes derived from the crafts were integrated into commercial production, creating what became known as the industrial arts.

The thread running through Scandinavian design is functionalism. For hundreds of years, the need for products to just work was ingrained in the Scandinavian soul. It hadn’t been very long since this was a requirement for survival. The focus was on “need,” or function, not on decoration or beauty.

Moving into the machine age, surviving became easier, and functionalism evolved into also meeting the emotional needs of people. This gave Nordic functionalism a more natural and humanistic side. But there still existed more extreme approaches to functionalism, which stripped all decoration in favor of pure function.

The long winters and few hours of sunlight inspired Scandinavian designers to create bright, light, practical environments. They tried to make the domestic environment as comfortable as possible with the materials at hand. These trends were picked up by neighboring countries and eventually spread all over the world. The high-quality designs live on today and are recreated continually in various fields, confirming their timelessness.

Arne Jacobsen’s timeless designs in furniture and architecture are well known, and his contributions to the creative fields are secure in history. After winning several architectural competitions, Jacobsen became known for designs that brought futuristic visions into a present-day context. His simple yet effective chair designs enjoyed worldwide success.

Poul Henningsen’s distinctive lamp designs were well thought out. He looked for solutions to spread the light of a bulb as widely as possible without the glare being visible. It’s a good example of Scandinavian design: the beauty of the elegant smooth lines doesn’t prevent the lamp from performing its function exactly as it was designed to do.

Scandinavian design has been perhaps most widely recognized in furniture, which spread the principles of its creators. Other fields, such as graphic design, followed these principles, particularly with regard to production and availability.

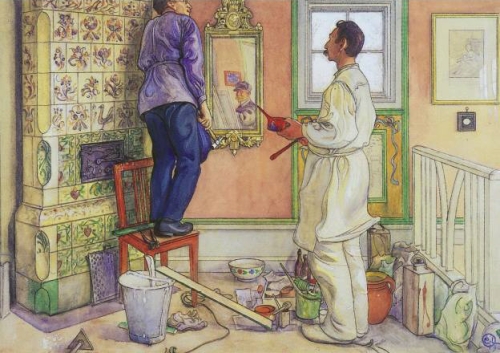

The Scandinavian style isn’t only form-bent wood furniture in various shades of white and nature-inspired patterns and shapes. Splashes of color have been a big part of Nordic interiors for a long time. Late-19th century Swedish artist and designer Carl Larsson is famous for his bright and colorful paintings. His watercolors of painted furniture and folk art have been highly influential in Scandinavia.

One of Denmark’s most famous designers, Verner Panton, is known for his bold and abstract work in the ’60s, with a focus on new materials. Panton’s creations stood apart from those of his contemporaries, and his focus was more on what we today associate with Pop Art. Strong, dramatic colors and futuristic shapes dominated his work. His designs, along with those of Finnish designer Eero Aarnio and Finnish-American Eero Saarinen, have been used in a number of film productions and countless photo shoots to create a futuristic look.

Today

Scandinavian design has evolved with the times, moving from mostly furniture and product design to an application of principles and processes to current problems and opportunities. Its change has been just as dramatic as the society it’s a part of.

As mentioned, Scandinavian countries established institutions early on to promote and protect the various design industries. Svensk Form in Sweden demonstrates the benefits of good design for social development. The Danish Design Center highlights the value of design for Denmark-based businesses. The Iceland Design Centre organizes lectures and exhibitions and facilitates collaboration between local designers and artists. The Norwegian Design Council promotes design as a strategic tool for innovation. And the Nordic countries are home to some of the most interesting conferences in art and design, such as Iceweb (the Icelandic Web conference), Copenhagen Fashion Week and the Stockholm Furniture Fair.

The Scandinavian aesthetic, of mass-produced design that is accessible and available to all, with a touch of grace, reminds the user that the product’s creator is human.

In the digital world, where the interface for so many designs is keyboard, mouse and screen, the creator is sometimes forgotten. The human element is demoted in favor of expediency and functionality.

In an article about the utilitarian excellence of Scandinavian design, Lara Iziercich explains what makes the Scandinavian style so different.

Scandinavian marketing involves little more than promoting designs which are developed according and appropriate to the needs of the consumer. They aren’t intent on “selling” new design concepts to consumers. Scandinavian designers pride themselves on only creating functional, durable and cost- efficient products and goods. If people need something, they will buy it. If they don’t [need it], it doesn’t exist on the market to begin with.

The principles of Scandinavian design — of prioritizing functionality without eliminating grace and beauty — might be a very good approach to Web design today. Granted, when Web design emerged as a profession, it focused mainly on functionality anyway, with some of it better executed than others. It wasn’t until graphic Web browsers started to dominate that graphics began to be heavily incorporated in Web design. How well Scandinavian functionality translates to the Web is debatable, and overgeneralizing is hardly fair. While most designers strive to keep their work functional, some have had more success than others.

Steadily yet quickly, Web designers have become masters of many trades that were once the domains of discrete professions. The beautiful thing is that, although Web designers have taken on more and more roles, these older professions have not died out. They evolved alongside the Internet. Today, Web design encompasses many fields, all working towards the goal of creating functional products.

Scandinavian design has certain standards, and Web standards are currently being discussed and agreed on worldwide. Of course, some personal projects, niche websites and other Web designs do not focus purely on functionality, but rather exist to showcase a product or technique. All of these are as much a part of the Web design profession as everything else we’ve looked at. Intense debates and exchanges of opinion most often lead to further refinement and understanding of this young profession. And the field’s practitioners seek inspiration everywhere, constantly pushing the aesthetic, technological and functional boundaries of computers and the Internet.

While natural, bright, uncluttered design is popular in online content today, saying that all clean, simple and functional Web design today has its roots in Scandinavian design would be an overstatement.

With technology changing fast and getting more and more complex, it is as important as ever to know your tools and their possibilities. Businesses depend on having an online presence that is well thought out and that gives the visitor a good experience. Interaction with products and services has become a focal point of both offline and online user experiences.

When each day brings new ways to redefine design, the long-established principles of Scandinavian design — usability and simplicity, while retaining an element of humanity and of grace and beauty — could be key to achieving a successful outcome.

In The End

Art and design mirror the society they are a part of. But with the globalization of ideas increasing and the world of communication shrinking, a design will not be influenced solely by the culture in which it originates.

Being from Scandinavia myself, I can’t help but feel a close connection to the design here. It has certainly influenced my work: I have found myself at times wanting to adhere to its traditions and at other times distancing myself from them. But with a background in product design and media arts, I am used to keeping my eye open to ideas. Designer Simon Collision puts it well:

I believe that perception and meaning cut through disciplines, so something learned decades ago by an architect or furniture designer could help me understand elements of my work on the Web. I’d rather we investigate experiences and ideas than simply leverage everything from print design, as some suggest.

Regardless of how much this applies to your own design process, context almost always adds value to your work, whether you intend it to or not.

The democratic and humanistic principles spread by Scandinavian design and the sensitivity to materials and to researching and employing traditional methods are an important and influential part of design history. It’s worth diving into Scandinavian design, including its history, context and connotations, to discover all that it has to offer.

Understanding your materials and connecting with them emotionally will help you better conceptualize your work and in turn help your audience better connect with it. Scandinavian design history is a deep well of information and inspiration, whether for online content, furniture, sculpture or any of the many other aspects of life that designers and artists encounter daily.

Resources Referred to in This Article

- “Art Nouveau in Europe,” David Ryan.

- “Skønvirke” (in Danish), Den Store Danske Gyldendals Åbne Encyklopædi.

- “Anxiety and Desire: Surrealism in Scandinavia 1930–1950,” Ausra Larbey.

- “About Svensk Form,” Svensk Form.

- “Funkis Returns,” Nordic Wellbeing.

- “The Surprising Side of Scandinavian Design,” Laura Fenton.

References

- Copenhagen Fashion Week

- Outline for grade 12 Visual Arts course, Iona Catholic Secondary School.

- Danish Design Center

- Design in Scandinavia exhibition, Brooklyn Museum Archives.

- “The Story of Finn Juhl” (PDF), One Collection.

- “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism” (English translation), F. T. Marinetti.

- “Good Designers Learn From History,” RetinArt.

- Iceland Design Centre

- IceWeb Conference

- Marimekko

- Modern Swedish Grammar, Immanuel Bjorkhagen.

- Norwegian Design Council

- “Scandinavian Design,” Kerstin Wickman, Nordic Way.

- “Scandinavian Web Design,” Slightly Ajar.

- Stockholm Furniture Fair

- Svensk Form

- “Swedish Design Inspiration,” Viget Labs

- Swedish National Heritage Board’s Flickr photostream

- “Type Design: A Part of Danish Design Tradition,” Mind Design.

Copyrights

This article is partly based on the following copyrighted Wikipedia articles, used under the Creative Commons Attributions-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA):

- Scandinavian design,

- Futurism,

- De Stijl,

- Vladimir Tatlin,

- Wassily Kandinsky,

- El Lissitzky,

- Alexander Rodchenko,

- Malevich,

- Stenberg brothers,

- Bauhaus,

- Modernism,

- Dada,

- Skønvirke,

- Marimekko,

- Arne Jacobsen,

- Svensk Form,

- Södra Ängby,

- Academic art,

- Futurist Manifesto,

- Social realism.

Further Reading

You might want to take a look at the following related articles on Smashing Magazine:

- Modern Art Movements To Inspire Your Logo Design

- Lessons From Swiss Style Graphic Design

- The Beauty Of Typography: Writing Systems And Calligraphy Of The World

- Bauhaus: Ninety Years of Inspiration

Agent Ready is the new Headless

Agent Ready is the new Headless

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App