Why We Shouldn’t Make Separate Mobile Websites

There has been a long-running war going on over the mobile Web: it can be summarized with the following question: “Is there a mobile Web?” That is, is the mobile device so fundamentally different that you should make different websites for it, or is there only one Web that we access using a variety of different devices? Acclaimed usability pundit Jakob Nielsen thinks that you should make separate mobile websites. I disagree.

Jakob Nielsen, the usability expert, recently published his latest mobile usability guidelines. He summarizes:

“Good mobile user experience requires a different design than what’s needed to satisfy desktop users. Two designs, two sites, and cross-linking to make it all work.”

I disagree (mostly) with the idea that people need different content because they’re using different types of devices.

Firstly, because we’ve been here before, in the early years of this century. Around 2002, the huge UK supermarket chain Tesco launched Tesco Access—a website that was designed so that disabled people could browse the Tesco website and buy groceries that would be delivered to their homes.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- How To Build A Mobile Website

- The (Not So) Secret Powers Of The Mobile Browser

- How To Use CSS3 Media Queries

- Breakpoints And The Future Of Websites

It was a great success—heavily stripped down, all server-generated (as in, those days screen readers couldn’t handle much JavaScript) and it was highly usable. One design goal was “to allow customers to purchase an average of 30 items in just 15 minutes from login to checkout.” In fact, from a contemporary report, (cited by Mike Davis), “many non-disabled customers are switching from the main Tesco site to the Tesco Access site, because they find it easier and faster to use!” It also made Tesco a lot of money: “Work undertaken by Tesco.com to make their home grocery service more accessible to blind customers has resulted in revenue in excess of £13m per annum, revenue that simply wasn’t available to the company when the website was inaccessible to blind customers.”

However, some blind users weren’t happy. There were special offers on the “normal” Tesco website that weren’t available on the access website. There were advertisements that were similarly unavailable—which was a surprise; whereas most people hate advertisements, here was a community complaining that it wasn’t getting them.

The vital point is that you never know better than your users what content they want. When Nielsen writes that mobile websites should “cut features, to eliminate things that are not core to the mobile use case; [and] cut content, to reduce word count and defer secondary information to secondary pages,” he forgets this fact.

“We have completely redesigned Access so that it is no longer separate from our main website but is now right at the center of it, enabling our Access customers to enjoy the same features and functionality available on the standard grocery website. As part of this work we have had to retire the old Access website.”

Nielsen writes:

“Build a separate mobile-optimized site (or mobile site) if you can afford it … Good mobile user experience requires a different design than what’s needed to satisfy desktop users. Two designs, two websites, and cross-linking to make it all work.”

From talking to people in the industry, and from my own experience of leading a dev team, I’ve found that building a separate mobile website is considered to be a cheaper option in some circumstances—there may be time or budgetary constraints. Sometimes teams don’t have another option but creating a separate website due to factors beyond their control.

I believe that this is not ideal, but for many it’s a reality. Re-factoring a whole website with responsive design requires auditing content. And changing a production website with all the attendant risks, then testing the whole website to ensure it works on mobile devices (while introducing no regressions in the desktop website)—all this is a huge task. If the website is powered by a CMS, it’s often cheaper and easier to leave the “desktop website” alone, and implement a parallel URL structure so that www.example.com/foo is mirrored by m.example.com/foo, and www.example.com/bar is mirrored by m.example.com/bar (with the CMS simply outputting the information into a highly simplified template for the mobile website).

The problem with this approach is Nielsen’s suggestion: “If mobile users arrive at your full website’s URL, auto-redirect them to your mobile website.” The question here is how can you reliably detect mobile browsers in order to redirect them? The fact is: you can’t. Most people attempt to do this with browser sniffing—checking the User Agent string that the browser sends to the server with every request. However, these are easily spoofed in browsers, so they can’t be relied upon, and they don’t tell the truth, anyways. “Browser sniffing” has a justifiably bad reputation, so is often renamed “device detection” these days, but it’s the same flawed concept.

On mobile, Twitter.com automatically forwards users to a separate mobile website.

More troublesome is that there are literally hundreds of UA strings that your detection script needs to be aware of in order to send the visitor to the “right” page. The list is ever-growing, so you need to constantly check and update your detection scripts. And of course, you only know about a new User Agent string after it turns up in your analytics—so there will be a period between the first visitor arriving with an unknown UA and your adding it to your detection scripts (in which visitors will be sent to the wrong website).

Despite all this work to set up a second parallel website, you will still find that some visitors are sent to the wrong place, so here I agree with Nielsen:

“Offer a clear link from your full site to your mobile site for users who end up at the full site despite the redirect … Offer a clear link from your mobile site to your full site for those (few) users who need special features that are found only on the full site.”

Missing out features and content on mobile devices perpetuates the digital divide. As Josh Clark points out in his rebuttal:

“First, a growing number of people are using mobile as the only way they access the Web. A pair of studies late last year from Pew and from On Device Research showed that over 25% of people in the US who browse the Web on smartphones almost never use any other platform. That’s north of 11% of adults in the US, or about 25 million people, who only see the Web on small screens. There’s a digital-divide issue here. People who can afford only one screen or internet connection are choosing the phone. If you want to reach them at all, you have to reach them on mobile. We can’t settle for serving such a huge audience a stripped-down experience or force them to swim through a desktop layout in a small screen.”

The number of people only using mobile devices to access the Web is even higher in emerging economies. Why exclude them?

Mobile Usability

I also agree with Nielsen when he writes:

“When people access sites using mobile devices, their measured usability is much higher for mobile sites than for full sites.”

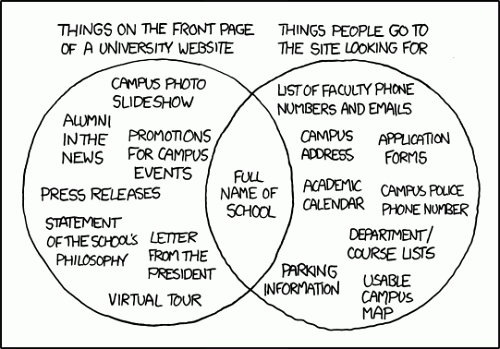

But from this he draws the wrong conclusion, that we should continue making special mobile websites. I believe that special mobile websites is like sticking plaster over the problem; we generally shouldn’t have separate mobile websites, anymore than we should have separate screen reader websites. The reason many “full websites” are unusable on mobile phones is because many full websites are unusable on any device. It’s often said that your expenditure rises as your income does, and that the amount of clutter you own expands to fill your house however many times you move to a bigger one. In the same way, website owners have long proved incontinent in keeping desktop websites focussed, simply because they have so much room. This is perfectly illustrated by the xkcd comic:

A Venn diagram showing “Things on the front page of a university website” and “Things people go to the site looking for.” Only one item is in the intersection: “Full name of school.” Image source: xkcd.

As I wrote on the website The Pastry Box on April 13th:

“The mobile pundits got it right: sites should be minimal, functional, with everything designed to help the user complete a task, and then go. But that doesn’t mean that you need to make a separate mobile site from your normal site. If your normal site isn’t minimal, functional, with everything designed to help the user complete a task, it’s time to rethink your whole site.“And once you’ve done that, serve it to everyone, whatever the device.”

In a previous article, Nielsen wrote in September 2011 that he dropped testing usability with featurephones:

“Our first research found that feature phone usability is so miserable when accessing the Web that we recommend that most companies don’t bother supporting feature phones.“Empirically, websites see very little traffic from feature phones, partly because people rarely go on the Web when their experience is so bad, and partly because the higher classes of phones have seen a dramatic uplift in market share since our earlier research.”

This is a highly westernized view. Many people can’t afford smartphones, so they use feature phones running proxy browsers (such as Opera Mini), which move the heavy lifting to servers. This is often the only way that underpowered featurephones can browse the Web. Statistics from Opera’s monthly State of the Mobile Web report (disclosure: Opera is my employer) shows that lower-end feature phones still dominate the market in Eastern Europe, Africa and other emerging economies—see the top 20 handsets worldwide for 2011 that accessed Opera Mini. Since February 2011, the number of unique users of Opera Mini has increased 78.17% and data traffic is up 142.79%.

A caveat about those statistics: not every user of Opera Mini is a featurephone user in developing countries. They’re widely used on high-end smartphones in the West, too, as we know that they are much faster than built-in browsers, and users really want speed.

Nielsen’s dismissal of feature phones reminds me of some attitudes to Web accessibility in the early 2000’s. His assertion that companies shouldn’t support feature phones because they see little traffic from feature phones is the classic accessibility chicken and egg situation: we don’t need to bother with making our website accessible, as no-one who visits us needs it. This is analogous to the owner of a restaurant that is up a flight of stairs saying he doesn’t need to add a wheelchair ramp as no-one with a wheelchair ever comes to his restaurant. It’s flawed logic.

Developing Usable Websites For All Devices

The W3C Mobile Web best practices say:

“One Web means making, as far as is reasonable, the same information and services available to users irrespective of the device they are using. However, it does not mean that exactly the same information is available in exactly the same representation across all devices. The context of mobile use, device capability variations, bandwidth issues and mobile network capabilities all affect the representation. Furthermore, some services and information are more suitable for and targeted at particular user contexts.”

There will always be edge cases when separate, mobile-specific websites will be a better user experience, but this shouldn’t be your default when approaching the mobile Web. For a maintainable, future-friendly development methodology, I recommend that your default approach to mobile be to design one website that can adapt to different devices with viewport, Media Queries and other technologies that are often buzzworded “Responsive Design.”

Combining these techniques in a smart way with progressive enhancement allows your content to be viewed on any device (and with richer experiences available on more sophisticated devices), with the possibility of accessing device APIs such as geolocation, or the shiny new getUserMedia for camera access.

Although many other resources are available, I’ve written “Mobile-friendly: The mobile web optimization guide” which you’ll hopefully find a useful starting point.

Further Reading

- Designers respond to Nielsen on mobile

- Nielsen responds to mobile criticism

- Let the mobile Web learn from and not repeat the mistakes of desktop development, by Henny Swan (2009)

- Notes on Designing Websites for the Asian Market, by Yours Truly

(jvb) (il)

In your experience, what kind of “mobile websites” do you create most often?

Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial Register For Free

Register For Free Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!