Be A Better Designer By Eating An Elephant

I can’t imagine any other industry in which so much change happens so quickly. If you stop paying attention for a week, it can feel like you’ve not been listening for a year. There’s so much to learn.

Falling behind is easy, too. We might be in the middle of a major project, so we put off learning about this newfangled thing called Sass or Node.js or even quickly experimenting with the new Bootstrap or Foundation that everyone is raving about. Before we know it, we have these elephants of missing knowledge wandering around our minds, reminding us of what we should know and do but haven’t found the time for.

Even just looking at beautiful work and seeing what new technique we could use ourselves can seem like too big a task when we’re swamped with projects. So, we tell ourselves we’ll come back to it later. But later never shows up. The guilt definitely does, but not that elusive deadline of later.

We feel guilty because we know something out there could help us become a better designer or developer and we’re not paying attention to it. Luckily, we can change this and start to catch up on what we’ve been missing out on.

Eating Elephants To Get Things Done

I always liked the productivity quip about how to start and finish a huge project: You do it the same way you eat an elephant, one bite at a time.

I’m not suggesting we go out and eat endangered animals, but what if we did just one small thing a day to expand our knowledge and skill set — and not just for a week or only on weekends, but every day, for 30 days straight? Would we catch up on that knowledge and experience we’re missing?

This challenge of stacking knowledge daily will enable you not only to learn 30 things, but to learn 30 things that will increase in complexity and fit together as a whole new branch of working knowledge for you.

How does that sound? Want to give it a go? It’s only 30 days, and it could alter the path of your career, even if slightly.

Pick A Challenge

Pick the right challenge, something that will keep you curious and excited for 30 days, something you’d be happy to chew on slowly. But the challenge should be able to be comfortably broken down into easy pieces, small bites.

Suppose you’re a web designer who wants to learn the CSS processor Sass. No shame in that; I’ll bet, like me, you’ve been very busy. But the prospect of learning Sass is kind of huge, isn’t it? What if we did it in the same way that we’d metaphorically eat an elephant?

Your day-one task might be to learn how to install Ruby and Sass locally. You can’t just be reading, though. That’s not learning — that’s memorizing. You have to do it as you go, downloading the installation files or loading the terminal.

Day two might be learning about and actually writing variables. Day three might be nesting. Days four through six might be setting up your files as partials. And then importing. And then mixins. Then, day seven could be inheritance. You might find that, once you’ve planned these days out, you have enough work for only 15 days, so maybe you’ll jump into learning Bourbon, Foundation or Bootstrap?

That all sounds like a lot to take on, especially if the names all sound intimidating. Biting them off one at a time would make things a lot easier. Downloading and installing a file might not seem like much, but tack that on to learning the basics over the next few days and you’ve started to develop a new skill.

But this isn’t about being perfect. You don’t need to build a beautiful website, or even a functional one. You just have to learn a collection of techniques and stay on track. To do so, to maintain focus, you need a plan.

Plan Your Bites And Prepare As Best You Can

You know what they say about the best laid plans of mice and men. So, avoid setting specific daily goals. Stumbling on day one would put you a day behind from the very start. A lacklustre performance for the following 29 days would then be almost certain. Rather than planning based on days, I’d suggest mapping your progress, which is really just a fancy way of saying “write a checklist” or even “keep a bucket.”

A Sass-loving designer would benefit from having an ordered list of, say, 45 to 60 things to learn and do. Some days, they’ll wake up and not get as much done as they’d like. Other days, they’ll work hard and everything will flow, and they’ll get two days’ worth of work done.

The other option is what I call a bucket. The bucket for my latest challenge was one of those nasty yellow “internal mail” envelopes, filled with topics I could write about. No need to be fancy about it: A list cut up into strips and then put into an envelope is all you need.

But why 45 to 60 topics and tasks if it’s a 30-day challenge? The bucket method makes things truly random, right up to the last day. Well, depending on the challenge, randomness might be exactly what you need. It worked well for me when doing my writing challenge.

Or, if you’re working with the map, it means you’ll focus more on the journey than on the destination. You’ll know well that you’re not going to finish everything in the 30 days, so you’re more likely to focus on what needs to get done day to day. You’ll also have leftovers, which will be perfect to keep you busy learning once the 30 days are up.

But where to find these small tasks? That depends entirely on the challenge you’re undertaking. Don’t overthink at this stage. You could spend far too much time worrying about learning the right thing that you’ll end up not learning anything at all.

For our Sass student, it could be as easy as going through introductory articles, both official ones and on blogs, or a series of classes on YouTube, or something structured like Lynda or curated like Gibbon, Oozled or HackDesign.

Set Time Goals, Limitations And Accountability

In The Creative Habit, Twyla Tharp talks about her morning gym routine. Her goal each morning isn’t to make it to the gym, but simply to get into a taxi. Once she’s done that, all she has to do to reach her morning goal is tell the driver to head towards the gym. Once there, she’ll exercise. What else is there to do? But her winning moment is getting into the taxi.

It seems to run counter to what was mentioned above about not setting goals for tasks, however, goals for start and finish times set us up for success. The real “work” is often simply showing up.

During my last challenge, dragging my foggy head from a warm and loving bed to my cold, sunless office proved to be a bigger challenge than I had anticipated. While the writing eventually became a natural part of my morning, getting to the desk did not.

Focusing on the seemingly insignificant goal of waking up and stumbling a few feet so that I could start typing meant that I had approached my task that day with a fresh accomplishment resting comfortably in memory.

Pressure is relieved before an initial effort is made, and with that first win comes the momentum to keep going. In these kinds of time goals you’ll find limitations and accountability. If you’re goal is to do two hours of work between 5:00 and 7:00 am, then your limit is 7:00.

Having a frequent finish time means that you’ll know how to ration out your effort, and your mind will appreciate the daily rest point that finishing provides. Once this kind of routine is established, you’ll be surprised by how easily you find the energy to keep working, often longer than you thought you would be able to, right up to the last minute.

Friends and followers will come to expect an outcome at the same time daily. Tweeting is simple, but throwing out a tweet at the same time every day sets up expectations for others. Getting a response, even if barely an occasional one, can keep you motivated for days.

Go!

You’re excited. You have your plan of attack; you have your small goals; and you’re ready to get to work and start chewing. Day one arrives and perhaps you wake before dawn, or you’re up when only the owls are about. Either way, you’re ready to work. On that first day and the few that follow, excitement isn’t hard to find. But with it comes a coating of struggle.

A part of you will ask why you’re bothering. You’ll wonder what benefit could possibly be derived from this silly little game you’re playing. Ignore such miserable thoughts. They’ll probably arrive whether you like it or not. And for the first few days you’ll find yourself frequently battling your internal resistance. This scares many, but it’s natural.

Chances are you’re doing something challenging, something you’ve never done before, in parts so small that they won’t seem to matter. The lizard in your brain will tell you that surfing TV or the Internet would be easier. But that will go away. For me, it always goes around day 10. I hope it’s sooner for you, but by day 10 I find that things have become incredibly automatic and the resistance has almost completely disappeared.

However, not long after this, things get too easy. You might even end up setting your own little time traps. For my latest writing challenge, I gave myself up to two hours to do the work, but near day 20 I realized that I could write a piece in less than a quarter of that, and so I would leave it until that was all the time I had left. I’d still wake up on time at be at my desk, but I would mindlessly surf and read. What a wonderful signifier of development leftover time is, but one that I embraced poorly.

Time would be much better spent being reinvested in skill development. You could get dramatic returns by pouring this time into increasingly difficult tasks, and your framework of knowledge would be the richer for it. I’d suggest aiming for discomfort instead of finishing quickly.

In a 30-day challenge, defining your daily problems is up to you, so make sure to revise your plan every day. Look at the task you did that day and adjust for the following days. Was it too hard? Then maybe simplify tomorrow’s expectations. Was it too easy? Spice it up somehow. Write more words, write more code, further develop a design.

You don’t develop when you practice what you’re already good at. Aim to finish with excitement, but not exhaustion.

It’s 30 Days Of Achievement, Not Just Knowledge

You’ve spent 30 days working on a challenge, but not so that the skills you develop become automatic, but to show yourself what you can achieve in a tiny window. You’ve found an hour or two a day and have probably lost nothing because of it. Just keep going.

From day 31, don’t think of what you’re doing as a challenge. It’s simply how you work. It’s how you plan your time, and it’s how you grow your knowledge. Don’t make the mistake I’ve made too many times and expect that once the 30 days are out the door, perfect autonomy will walk into the room.

Before you hit day 31, plan out what you’ll do next. Continue following the map or emptying the bucket, but top it up with another 30 or 50 items, and just keep working. Review frequently, as you would during the 30 days, keep your schedule, and ensure that you’re enjoying the right kind of challenge.

Perhaps this is the biggest gift of the 30 days: not the skills you acquire or any habit you set out to establish, but rather the realization that you can find the time, that you can learn something every day, and that planning your education is important.

Learning something daily is not hard. Some amazing websites will help you do it; they’ll give you some random, small, independent piece of knowledge that’s great to talk about over coffee but that won’t stack. And that is what’s valuable: stackable knowledge. You can start stacking with such a small number of days — just 30 of them.

30 days. That’s all it takes to learn a skill that could change your career.

You might be able to develop your skills to keep up with, and then break ahead of, the pack. You might be able to charge more because you can offer more or offer better. You could learn to better tell the stories of your clients, to produce work that is more sustainable or even delightful. With time, you could become an authority to whom others in your field, both students and professionals, call on for help in becoming more skilled and knowledgeable themselves. Instead of simply meeting standards and expectations, you could be setting them.

You could challenge yourself in ways you can’t imagine, pushing the edge of your knowledge and experience, finding new avenues previously hidden. Your work could becoming increasingly meaningful because of it, as every month or year finds you working at increasingly complex and sophisticated problems. You could, in ways both small and large, shape an industry that I’m willing to bet you love. All that, just because you worked on it an hour or two a day, one bite at a time.

The process is so simple. This is all you’re doing:

- Pick a topic.

- Break it down into parts.

- Map out or randomize those parts.

- Show up daily, at the same time, and get to work.

- Review progress, and make sure you’re being challenged just enough, adjusting as you go.

- Do it for 30 days.

Easy, isn’t it?

That’s how you take your daily bite. Soon, you’ll realize you’ve consumed an elephant-sized body of knowledge. You just have to show up and take action. Most of the people who read this article and like what they’ve learned will forget it all within a couple of hours or days. Or even minutes.

But not you. You’re going to work, and when you do, when you do this silly little challenge thing for 30 days, you’ll find yourself ahead of most of the people you know. Do it for 60 or 90 days or every single day for the rest of your career and you’ll be in a league of your own.

Pick your topic. Take action.

What’s Your Challenge?

What’s that thing you’ve been wanting to achieve? What’s that thing you’ve been wanting to learn?

- Always wanted to learn how to design your own font? Try a letter a day. Start small by copying a font you love.

- Need more experience with branding? Design one logo per day, or one brand per month. The first day could be research, the second could be brainstorming, the third sketching, all the way through to a polished style guide.

- Want to learn photography? What if you started by learning what a single setting on the camera does? Then, work your way through to composition, style and post-production?

- Want to learn to write? Grab any number of amazing books on writing, and read one rule or lesson per day. Then, write as many examples using that lesson as you can in an hour.

- Want to learn a programming language? Learn and practice one command per day, with the aim of building a small working prototype.

Let us know what you’ve chosen in the comments. It might keep you on point and, even cooler, might inspire others to join you on the path.

Whatever you decide to do, don’t put it off. Start next Monday. Don’t wait a month or three or start first thing next year. Start next week, maybe the week after if you have to work on your list of tasks. Just start. As soon as you can.

Resources

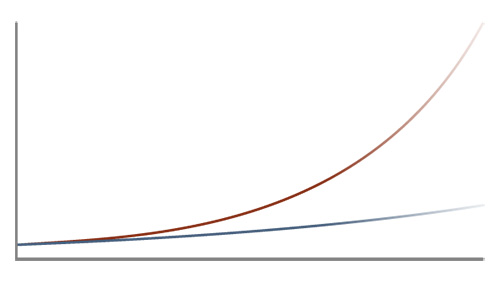

- Get one of those compound interest and investment charts that shows how just a small bit every day adds up.

- “Five Years of 100 Days,” Michael Beirut

Design legend Michael Beirut gives his students at Yale a 100-day design challenge. The results range from brilliant to hilarious. One of my favorites is Ely Kim’s “Boombox” dance challenge. - 100/100/100, Zak Klauck

Klauck undertook this challenge as part of Michael Beirut’s course at Yale. He designed a poster a day based on a short phrase or word, in only one minute. - “Design Something Every Day!,” Jad Limcaco, Smashing Magazine

In 2009, Limcaco interviewed a few designers and illustrators who were doing year-long challenges to make something every day.

A lot of learning and inspiration can be found in what’s been written about design and development sprints in the last couple of years:

- “Off To The Races: Getting Started With Design Sprints,” Alok Jain, Smashing Magazine

- “The Product Design Sprint: A Five-Day Recipe for Startups,” Jake Knapp, Google Ventures

- “Design Sprints For Developers,” Nadya Direkova, Google Developers Blog

- “The Product Design Sprint,” Galen Frechette, Thoughtbot

Further Reading

- Why Great Products Need Great Collaboration

- Drawing Inspiration From Music

- Professional Team Management Tips For Creative Folks

- Finding Your Tone Of Voice

(al, il, mrn)

(al, il, mrn)

Enterprise UX Masterclass, with Marko Dugonjic

Enterprise UX Masterclass, with Marko Dugonjic Register For Free

Register For Free JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding. Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why! Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial