How To Design For Smartwatches And Wearables To Enhance Real-Life Experience

Imagine two futures of mobile technology: in one, we are distracted away from our real-world experiences, increasingly focused on technology and missing out on what is going on around us; in the other, technology enhances our life experiences by providing a needed boost at just the right time.

The first reality is with us already. When was the last time you enjoyed a meal with friends without it being interrupted by people paying attention to their smartphones instead of you? How many times have you had to watch out for pedestrians who are walking with their faces buried in a device, oblivious to their surroundings?

The second reality could be our future – it just requires a different design approach. We have to shift our design focus from technology to the world around us. As smartwatches and wearables become more popular, we need to create design experiences that allow us to create experiences that are still engaging, but less distracting.

Lessons Learned From A Real-Life Project

We create a future of excessive distraction by treating our devices as small PCs. Cramming too much onto a small screen, and demanding frequent attention on a device that is strapped to your body means you can’t get away from the constant buzzing and beeping right up against your skin. Long, immersive workflows that are easily handled on a larger device become unbearable on a device that has less screen area and physical navigation space.

I noticed this on my first smartwatch project. By designing an application based on our experience with mobile phones, we accidentally created something intrusive, irritating and distracting. That meant the inputs and workflows demanded a lot of attention and were so involved that people had to stop moving in order to view notifications or interact with the device. Our biggest mistake was using the vibration motor on all notifications. If you had a lot of notifications, your smartwatch would buzz constantly. You can’t get away from it and people would actually get angry at the app.

How The Real World Inspired Our Best Approach

In a meeting, I noticed the lead developer glancing down at the smartwatch on his wrist from time to time. As he glanced down, he was still engaged in the conversation. I wasn’t distracted by his behavior. He had configured his smartwatch to only notify him if he got communications from his family, boss or other important people. Once in a while, he interacted with the device for a split second, and continued on with our conversation. Although he was distracted by the device, it didn’t demand his complete attention.

I was blown away at how different his experience was from my smartphone. If my phone buzzes in my pocket or my bag, it completely distracts me and I stop focusing on what is going on around me to attend to the device. I reach into my pocket, pull out the device, unlock the screen, then navigate to the message, decide if it’s important, and then put the device back. Now where were we? Even if I optimize my device settings to smooth some of this interaction out, it takes me much longer to perform the same task on my smartphone because of the different form factor.

This meeting transformed our approach to developing our app for the smartwatch. Instead of creating an immersive device experience that demanded the user’s attention, we decided to create something much more subtle. In fact, we moved away from focusing on application and web development experiences to focusing on application notifications.

Designing With A Different Focus In Mind

Instead of cramming everything we could think of on these smaller devices, we aimed for a lightweight extension of our digital virtual experience into the real world. You could get full control on a PC, but on the smartwatch, we provided notifications, reminders and short summaries. If it was important, and it could be done easily on a smartwatch, we also provided minimal control over that digital experience. If you needed to do more, you could access the system on a smartwatch, or a PC. We had a theory that we could replicate about 60% of PC functionality on a smartphone, and another 20% of that on a smartwatch.

Each different kind of technology should provide a different window on our virtual data and services depending on their technical capabilities and what the user is doing. By providing just the right information, at just the right time, we can get back to focusing on the real world more quickly. We stopped trying to display, direct and control what our end users could do with an app, and relied on their brains and imaginations more. In fact, when we gave them more control, with information in context to help solve the problem they had right then and there, users seemed to appreciate that.

Design To Enhance Real-Life Experiences

After the initial excitement of buying a device wears off, you usually discover that apps really don’t solve the problems you have as you are on the move. When you talk to others about the device, you find it difficult to explain why you even own and use it other than as a geeky novelty.

Now, imagine an app that reminds you of your meeting location because it can tell you are on the wrong floor. Or one that tells you the daily specials when you walk into a coffee shop and also helps you pay. Imagine an app that alerts you to a safety brief as you head towards a work site, or another app that alerts you when you are getting lost in an unfamiliar city. These ideas may seem a bit far off, but they are the sorts of things smartwatches and similar small screen devices could really help with. As Josh Clark says, these kinds of experiences have the potential to amplify our humanity.

How is this different from a smartphone? A smartphone demands your complete attention, which interrupts your real-world activities. If your smartwatch alerts you to a new text or email, you can casually glance at your wrist, process the information, and continue on with what you were doing. This is more subtle and familiar behavior borrowed from traditional wristwatches, so it is socially acceptable. In a meeting, constantly checking your smartphone is much more visible, disruptive, irritating and perceived as disrespectful. If you glance at your wrist once in a while, that is fine.

It’s important to remember that all of these devices interrupt our lives in some way. I analyze any interruption in our app designs to see if it has a positive effect, a potentially negative effect, or a neutral effect on what the user is doing at the time. You can actually do amazing things with a positive interruption. But you have to be ruthless about what features you implement. The Pebble smartwatch design guide talks about “tiny moments of awesome” that you experience as you are out in the real world. What will your device provide?

Keep The Human In Mind

Our first smartwatch app prototype was a disaster. It was hard to use, didn’t make proper use of the user interface, and when it was tested in the real world, with real-life scenarios, it was downright annoying. Under certain conditions, it would vibrate and buzz, light up the screen and grab your attention needlessly and constantly. People hated it. The development team was ready to dump the whole app and not support smartwatches at all because of the negative testing experience. It is one thing to have a mobile device buzz in your pocket or hand. It is a completely different thing to have something buzzing away that is attached to you and right up against your skin. People didn’t just get annoyed, they got really angry, really quickly – because you can’t escape easily.

Design For The Senses

I knew we had messed up, but I wasn’t sure exactly why. I talked to Douglas Hagedorn, the founder and CEO of Tactalis, a company developing a tactile computer interface for people who are sight-impaired. Doug said that it is incredibly important to understand that different parts of the body have different levels of sensitivity. A vibration against your leg in your trouser pocket might be a mild annoyance, but it could be incredibly irritating if the device vibrates the same way against your wrist. It could be completely unbearable if it is touching your neck (necklace wearable) or on your finger (ring wearable).

Doug also advised me to take more than one sense into account. He mentioned driving a car as an example. If all you do is provide a visual simulation for driving a car, it doesn’t feel correct to your body. That’s because driving a car also has different senses involved. For touch, there is the sensation of sitting in a seat, with a hand on the steering wheel and a hand on the gear shifter, as well as pedals beneath your feet. There are also sensations of movement and sound. All of these together provide the experience of driving a car.

With a smartwatch or wearable, depending only on one sense won’t help make the experience immersive and real. Doug advised using different notification features on the devices to signify different things. Design so that physical vibrations are for one type of interaction and a screen glow is used for another. That way the user observes a blend of virtual experiences similarly to how they experience the real world.

Understand Context

Because the devices are attached to us, they constantly move, and are looked at and interacted with at awkward angles. Users must be able to read whatever you put on the screen, and easily interact while moving. When moving, it is far more difficult to read and input into the screen. When sitting down, the device and your body are more stable and we can tolerate far more device interaction. Ask critically:

- What are people going to be doing when using our app?

- Where will they be?

- What happens when the user is moving versus sitting down?

It’s critical to understand the device interactions: taps, gestures, voice control, physical buttons and dials.

Understand Emotions

Our emotions vary depending on experiences and contexts, which can be extremely intense and intimate, or bland and public. Our emotional state at a particular point in time has an enormous impact on what we expect from technology. If we are fearful or anxious and in a rush, we have far less patience for an awkward user experience or slow performance. If we are happy or energetic, we will have more patience with areas where the app experience might be weaker.

Since these devices are taken with us wherever we go, they are used in all sorts of conditions and situations. We have no control over people’s emotions so we need to be aware of the full range and make sure our app supports them. It’s also important to provide user control to turn off or mute notifications if they are inappropriate at that time. When people have no control over something that is bothering them, negative emotions can intensify quickly.

- Spend time on user research and create personas to help you understand your target user.

- Create impact stories for core features – a happy ending story, a sad ending story, and an unresolved story.

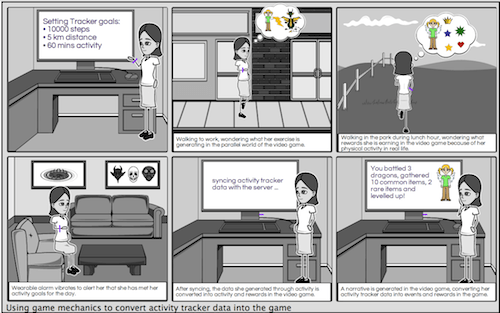

- Also create storyboards (see Figure 2) to demonstrate the fusion of your virtual solution with the real world.

We usually spend more time on these efforts than the visual design because we can incorporate context, emotions, and error conditions early on. We can use these dimensions to analyze our features and remove those that don’t make sense once they meet the real world

It is incredibly important to test away from the development lab, out of your building. It is vital to try things out in the real world because it has very different conditions to a development lab. For each scenario, also simulate different conditions that cause different reactions and make them realistic:

- Simulate stress by setting impossible timelines on a task using the device.

- Simulate fear by threatening a loss if the task isn’t completed properly.

- Simulate happiness by rewarding warmly.

Weather conditions have an effect as well. I am far less patient with application performance when it is cold or very hot, and my fingers don’t work as well on a touchscreen in either of those situations. As devices will be used in all weathers, with all kinds of emotions and time pressure, simulating these conditions when testing your designs is eye-opening.

Minimize Interruptions

When we do need to distract people, we should make the notifications high-quality. As we design workflows, screen designs and user interactions, we need to treat them as secondary to the real world so we can enhance what is going on around people rather than detracting from their day-to-day lives.

Try to create apps for notifications and lightweight remote control that help focus on creating an experience that relies on quick information gathering, and making the odd adjustment on the fly. Users stop, read a message, interact easily and quickly, and then move on. They spend only seconds in the app at any given time, rather than minutes.

The frequency of notifications should be minimal so the device doesn’t constantly nag and irritate the wearer. Allow the wearer to configure timing and types of notifications and to easily disable them when needed. During a client consultation it might be completely inappropriate to get notifications, whereas it might be fine while commuting home. Also provide users with the final say in how and when they are notified. A vibration and a screen glow is fine in some contexts, but in others, just a screen glow will suffice since it won’t disturb others.

Design Elegant And Minimalistic Visual Experiences

One of my favorite stories of minimalism in a portable device design is from the PalmPilot project. It’s said that the founder of Palm, Jack Hawkins, walked around with a carved piece of wood that represented the PalmPilot prototype. Any new features had to be laid out physically on the block of wood, and if there wasn’t room on it they had to decide what to do. Could the features be made smaller? If not, what other feature had to be cut from the design? They knew that every pixel counted. We need to be just as careful and demanding in our wearable app decisions.

Since these devices have small screens or no screens, there is a limit to the information that is displayed. For example, prioritize to show only the most important information needed at that moment. Work on summaries and synthesizing information to provide just enough. Use a newspaper headline rather than a paragraph.

Small Screens

Screens on wearables are very small and the resolutions can feel tiny. These devices also come in all shapes and (small) sizes. Beyond various rectangular combinations, some smartwatch and wearable screens are round. It’s important to design for the resolution of the device as well, and these can vary widely from device to device. Some current examples are: 128×128px, 144×168px, 220×176px, 272×340px, 312×390px, 320×290px, and 320×320px.

Screen resolutions on all devices are increasing, so this is something to keep on top of as new devices are released. If you are designing for different screen sizes, it is probably useful to focus on aspect ratios, since this can reduce your design efforts if different sizes share the same aspect ratio.

When working on responsive websites, you may encounter resolutions as high as 2,880×1,800px on PC displays, down to 480×320px on a small smartphone. When we designed for wearables we believed we could simply shrink the features and visual design further. This was a huge mistake, so we started over from scratch.

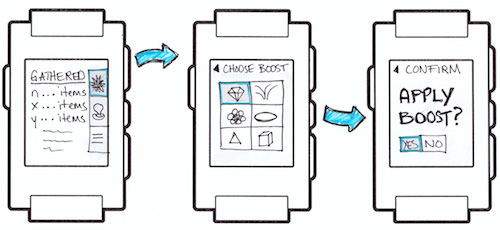

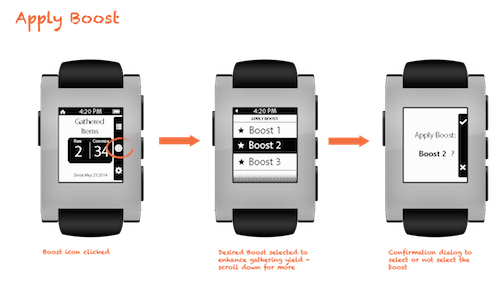

We decided to sketch our ideas on paper prior to building a prototype app. This helped tremendously because we were able to analyze designs and simulate user interactions before putting a lot of effort into coding. It was difficult to reach our app ambitions with such a tiny screen. A lot of features were cut, and it was painful at first, but we got the hang of it eventually.

No Screens

Many wearables have no screens at all, or they have a minimal screen that is reminiscent of an old LCD clock radio. Many devices are limited to UIs that only contain number shapes, a limited amount of text and little else. Other devices have no screen at all, relying on vibration motors and blinking lights to get people’s attention.

App engagement while wearing no-screen devices occurs mostly in our brains, aside from the odd alert or alarm through a vibration or blinking light. When devices are synced, a corresponding larger screen offers more details. This multiscreen experience reinforces the story narrative while they are away from a screen using only a wearable. This is more of a service-based approach than a standalone app approach. User data is stored externally (in the cloud), and display, interaction and utility are different depending on the device. The strong narrative that is reinforced in higher-fidelity devices helps persist it across device types. This different view on user-generated data also encourages self-discipline, a sense of completion or accomplishment, competition, and a whole host of feelings and emotions that exist outside of the actual technology experience.

Design Aesthetics

Design aesthetics are incredibly important because wearables extend a user’s personal image. Anything that we put on the screen should also be visually pleasing because it will be seen not only by the wearer but those around them. Minimalist designs are therefore ideal for smartwatches and wearables. Make good use of formatting and the limited whitespace. Use large fonts and objects that can be seen and interacted with while on the move. If you can, use a bit of color to grab attention and create visual interest.

Use Physical Inputs To Simplify Workflows

While our visual designs became more minimalist, we made the mistake of not researching what was possible with the software development kit (SDK) and the physical inputs available on the device. We ended up with some design ideas that weren’t feasible.

Since the devices are smaller and have lower fidelity, focus on their capabilities rather than trying to do something they aren’t capable of. It’s more important to support simple tasks and alerts than trying to create a full-blown productivity app that is better suited to a larger screen on a more powerful device. A pared down design is easier to use and makes better use of device resources, which can save battery life. Don’t try to do it all on every device type. Your wearable device users will also have a larger screen device that they can work with later, so try to target activities that are best suited for different device types.

Model workflows carefully to minimize effort, concentration and thinking. Instead of counting clicks as we do for PCs, count all types of interactions and try to reduce the number as much as possible. Always take the physical interactions and context of the user into account. Do more with less by pre-populating required input fields, making good use of shortcuts with buttons, touch screens and gestures.

The sketch in Figure 4 is a good start, but when we modeled user interactions we realized it would take a lot more effort to interact with than we wanted. To create something more realistic, we created high-fidelity mockups (see Figure 5) using the controls that were available through the API. The design template helped focus our design brainstorming, and we had ideas that were feasible to develop, still leaving room for our visual designer to take it to the next level. Subsequent sketches were done using the UI controls that were available in the API.

Incorporate The Real World Into Your Design

When you incorporate the real world into your app design, you can simplify your workflow on the device. There are a couple of ways to do this:

- Be aware when the user is using location services, and provide options to help enhance what a person is doing right now. For example, if the user is in a restaurant, an app could help with payment options, or provide instant information on daily specials.

- Use real-world objects as non-screen focal points to complement the app user interface. Specific locations, landmarks, buildings, physical and geographical features and points of interest link the virtual experience with a physical experience, and require more of our senses. Smartwatches and wearables are ideal platforms to support activities in the real world having a direct effect in a virtual world.

Incorporating physical cues can be fun. We created an app to encourage PC gamers to exercise while using smartwatches and mobile devices. Using location services, we superimposed a video game map onto the gamer’s real world to help extend game play away from the PC. As they moved through the real world with a smartwatch, players got notifications when passing by landmarks that held significance to them both in real-life, and in the game. The game app would supplement the real world experiences by notifying the user about their virtual rewards. When they returned to the PC they could incorporate these rewards in their game play. Thus, we rewarded them in the game for exercising in the real world and greatly reduced our smartwatch user interface design efforts.

My colleague John Carpenter, who helped develop a feature phone game called Swordfish, also used the real world for gameplay. His team used generic physical cues but left their interpretation up to the user. Instead of asking a player to go to a particular landmark, they used generic terms: “Go to a nearby store” or “Find a location with a river and a large tree”. This offered much more flexibility and interest, and was far less restrictive than going to exact locations (it also required less design and development work). The most powerful tool is the human mind, so why not encourage it in our designs?

However, bridging the physical and virtual worlds and using your imagination isn’t limited to gamers. When I start looking at the real world as a primary user interface, it has an enormous impact on my approach to designing experiences on wearable devices. Rather than trying to replace real-world objects (e.g. virtual paper, folders, garbage bins, etc.) we can use the real thing and supplement our interactions with those real things.

Understand Your Technology

If you understand the technology and what it was designed to do, you can exploit its strengths rather than bumping up against its limitations. For example, even though I knew better, I spent far too much time brainstorming and sketching out app ideas for smartwatches before studying their capabilities carefully. By mirroring smartphone designs I had made in the past, I ended up with unworkable solutions in some cases, and I didn’t take advantage of the strengths of the technology. It’s vital to understand how the smartwatch or wearable you are designing for is composed.

Restrict your use of the technical resources of the device. They are not as powerful as mobile phones or PCs. Using a lot of memory, inputs and outputs, processing power, and wireless connections will tax the device. At best this will result in poor app performance, and the device battery will drain very quickly. At worst, a lot of processing can cause the device to heat up. These devices don’t have cooling fans, they rely on managing their resources to try to cool themselves down. Remember that the device is going to be attached to a person and touching their skin. It will be very uncomfortable to wear a hot, overheated device.

Sensor-Based Devices

One easily overlooked aspect is the use of sensors. In fact, with wearables, screens play a secondary role to sensors. There are movement sensors such as the accelerometer, gyroscope and magnetometer to help measure a user’s movements, and support user interactions. They can also help determine accurate user location. Some devices contain health-related sensors that can measure heart rate, temperature, skin conductance and others. There are also device optimization sensors to deal with low battery, overheating, and if there is a screen, different lighting conditions.

These examples aren’t exhaustive. There can be sensors for touchscreens, proximity, off-device inputs, sound and all sorts of things that we already see in smartphones. Sensor prices have fallen over the past few years, and they are also becoming smaller, so the possibilities to use more of them in smartwatches and wearables are enormous. Make sure you understand all the sensors that are being used in the device so that you can use them to your advantage in your app designs.

Wireless

Smartwatches may be tethered to a mobile device, or they can be standalone devices with mobile wireless technology inside. The device can have a wireless radio to connect to telecommunications systems to communicate using cellular towers and Wi-Fi. In addition to data and communications, wireless is also used in location services, from GPS to using Wi-Fi and cellular tower locations to determine user location.

Tethered devices use short-distance wireless to communicate to a smartphone. Bluetooth is the most common way of connecting a smartwatch to a mobile phone. The smartwatch or wearable tethered to a mobile device depends on that mobile device to work properly. The smartphone does the heavy lifting for processing, location services and cellular or Wi-Fi. The tethered device’s app experiences provide a summarized view of what is normally available on the smartphone.

Both of these kinds of devices depend on wireless technology to work properly. For the best experiences, wireless needs to work flawlessly. However, wireless can be subject to interference from objects (especially those that contain steel), other devices, and even weather conditions. It’s important to understand that your app experience will be terrible if it utilizes wireless technology poorly, or can’t handle variable signal strengths, interruptions or temporary outages. It’s important to trap these poor conditions and provide error handling to help the user fix the problem.

Any time an app downloads files from a server, it has to go over a wireless network. If your wearable is tethered to your smartphone, then the smartphone has to connect with one wireless system, then communicate with the wearable using another. Problems can crop up along this path with poor signal speed, interference, and timing issues. Any files that need to appear on the wearable must be optimized so that they don’t take too long to download.

Remember, if a user is on a cellular network, and your app has large files, you could be costing them too much money. You can also force users over their cellular data plans and cause poor app performance if your files are optimized but require too much server interaction and many small downloads. If users exceed their data plan limit on their cellular contract, your app can incur significant costs. Be conscious of this, and design defensively.

Error Handling

Because of their smaller form factor, it takes more effort to troubleshoot and fix problems with your app on a wearable device. Anything that takes the focus off of what you are doing now and isn’t helping you solve your current problem or enjoy your surroundings more is a threat to a great user experience. Try to include error handling that automates tasks such as dealing with wireless connection or location issues, but be sure to allow your users to correct or override problems. Since they depend on wireless interaction, do your best to make this as bulletproof as possible, because the device’s utility depends on how it can handle different wireless conditions.

Study the error handling features of each device carefully, but APIs may not provide exactly what you need for great error handling. Since these devices are in their infancy, ask providers to support you if their error handling is weak in some areas. Don’t be afraid to ask, ask again and ask some more. If enough of us ask, they will provide.

Look At Past Technology To Find Adequate Solutions

I prefer approaching wearable technology by solving the problem traditionally first, without computing power, and then adding in technology features one by one. I find this much easier than reviewing the specs and API of a device and trying to fit all the options in all at once. I strip down the problem we are trying to solve using pre-computing technology. What can be done with a paper, pen, calculator, file folders, telephone, reference books, and things like that? Could they solve the problem with old technology? Once I have this mapped out, it is easy to find the areas where modern technology is superior, or facilitates a great user experience.

One area of inspiration for me is to look at older books and articles for feature phone development. Many of the feature phone app experiences were developed for technology and screen resolutions that are very similar to smartwatches. Reading through these guides and ideas is an absolute gold mine, and boosts my own design efforts for smartwatches. Handheld GPS units and geocaching were also hugely influential on my smartwatch and wearable designs.

Think Outside The Box To Engage Your Users

It’s possible to integrate wearable experiences into applications that reside outside of the device’s core focus. The trick is to convert the data generated by the device. A lot of user-generated data is made available through the provider’s API, so you can use their open systems to create something meaningful in your own app experiences.

They might have nothing to do with the core features of the wearable device gathering the data, but if you have a great PC or mobile-based experience to anchor to wearable activities, plus a compelling story that people can keep in mind while they are using the device, you can still engage them effectively.

For example, Virgin created an employee engagement application to encourage exercise. If an employee uses the activity tracker, they receive points for exercising in a corresponding employee application. These points are then converted into something meaningful for the employees. Some systems even convert exercise points into real-world bonuses such as gifts. This requires designing an entire service, with different types of devices offering different views and capabilities.

If you do convert data, be sure the mechanisms are published, open and fair. Currency conversion systems are a good area to study on how to do this correctly. Also ensure you are also legally compliant in your jurisdiction if you convert virtual points into real-world products.

Test, Test, Test

It’s also vital to try real-life scenarios out in the real world. Test, test and test some more. There is nothing like real world experience to determine whether you got it right or not. Prepare for a lot of user testing, and embrace all negative feedback. Anything that causes negative emotions needs to be worked out. Ask for reports on what interruptions are useful, useless or downright annoying. Identify any “tiny moments of awesome” they experience. You will get it right eventually, provided you listen to your testers and adjust accordingly.

Conclusion

Mobile technology has brought us some fantastic benefits, but with always available, always connected technology, it can have a negative impact when it demands our attention and distracts us from the real world. If we make sensible design choices, technology fades into the background, merely enhancing the here and now.

Using the real world as your core focus rather than the device is one approach to designing for this future. If you’re like me, you have spent years trying to make the virtual world mimic the real world. However, with wearables and devices like smart watches, the real world around us provides a rich canvas to design in, and it has a higher resolution and is more realistic than any computer.

Further Reading

- Getting Started With Wearables: How To Plan, Build And Design

- Bringing Your App’s Data To Every User’s Wrist With Android Wear

- Developing For Apple Watch Without The Device

- Intimate And Interruptive: Designing For The Power Of Apple Watch

- How We Designed And Built Our First Apple Watch App

How To Measure UX and Design Impact, 8h video + UX training

How To Measure UX and Design Impact, 8h video + UX training

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why! Register For Free

Register For Free

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.