Static Site Generators Reviewed: Jekyll, Middleman, Roots, Hugo

Static site generators are quickly becoming a big part of the professional website builder’s toolbox. A new static website generator seems to pop up every week. Figuring out which one to use can be like a walk in the jungle.

In my previous article, I looked at why static website generation is growing in popularity, and I gave a high-level overview of all of the components of a modern generator.

In this article, we’ll look at four popular static website generators — Jekyll, Middleman, Roots, Hugo — in far more detail. This should give you a great starting point for finding the right one for your project. A lot of other ones are out there, and many of them could have made this list. The ones I chose for this article represent the different trends that dominate the landscape today.

Each generator takes a repository with plain-text files, runs one or more compilation phases, and spits out a folder with a static website that can be hosted anywhere. No PHP or database needed.

Jekyll

No article today about static website generation can get by without mentioning Jekyll.

We might not be talking about the resurgence of static websites if GitHub’s founder, Tom Preston-Werner, hadn’t sat down in his San Francisco apartment in October 2008 with a glass of apple cider and the urge to write his own blogging engine.

The result was Jekyll, “a simple, blog-aware, static site generator.”

One of the brilliant ideas behind Jekyll is that it lets any normal static website be a valid Jekyll project. This makes it one of the easiest generators to get started with:

- Take a plain HTML mockup of a blog.

- Get rid of repeating headers, menus, footers and so on by working with layouts and includes.

- Turn pages and blog posts into Markdown, and pull the content into the templates.

Along the way, Jekyll can act as a local web server and keep watch over any files in your project, generating all of the HTML, CSS and JavaScript files from templates, Markdown, Sass or CoffeeScript files.

Jekyll was the first static generator to introduce the concept of “front matter,” a way of annotating templates or Markdown files with meta data. Front matter is a bit of YAML at the top of any text file, indicated by three leading and following hyphens (—):

title: A blog post

date: 2014-09-01

tags: ["meta", "yaml"]

---

# Blogpost With Meta Data

This is a short example of a Markdown document with meta data as front matter.

Templating Engine

Jekyll is built on Liquid, a templating engine that originated with Shopify. This is both a blessing and a curse. Liquid is a safe templating engine made to run untrusted templates for Shopify’s hosted platform. That means there is no custom code in the templates. Ever.

On the one hand, this can make templates simpler and more declarative, and Liquid has a good set of filters and helpers built in out of the box.

On the other hand, it does mean you have to start creating your own Liquid helpers from Jekyll plugins if you want to do anything that’s not baked in.

Liquid lets you use variables in your templates like this: {{ some_variable }}. And blog tags looks like this: {% if some_variable %}Show this{% endif %}. Jekyll adds a few tags to handle includes and links, plus some helpers for sorting, filtering and escaping content. One glaring omission is a simple way to handle default values for variables. At some point in the future, {{ some_variable | default: ‘Default Value’ }} should start working, but it’s not there yet. So, right now you’ll find a lot of clunky if and else statements in Jekyll websites that work around this.

Content Model

Jekyll’s content model has evolved a lot since the tool was conceived as a simple blogging engine.

Today, content can be stored in several different forms and take on different behavior.

The simplest form is an individual document in either Markdown or HTML. This file gets converted into a corresponding HTML page when the page is built. The document can specify a layout that will be used when it is turned into an HTML page, as well as specify various meta data, which you can access from templates via the {{page}} variable.

Jekyll has special support for a folder named _posts that contains Markdown files with a naming scheme of yyyy-mm-dd-title-of-the-post.md. Posts behave like you would typically expect from entries on a blog.

Since version 2.0, Jekyll supports collections. A collection is a folder with Markdown documents. You can access collections in templates through the special {{site.collections}} variable, and you can configure each document in the collection to have its own permalink. One big upcoming change in Jekyll 3.0 is that the distinction between _posts and collections will be eliminated.

The last form of content is data files. These are stored in a special _data folder, and they can be YAML, JSON or CSV files. From there, you can pull the data into any template file through the {{site.data}} variable.

Asset Pipeline

Jekyll’s asset pipeline is extremely simple. Just as with the logic-less Liquid, this is both good and bad. There’s no built-in support for live reloading, minification or asset bundling; however, Sass and CoffeeScript are pretty straightforward to handle. Any .sass, .scss or .coffee file that starts with YAML front matter will be processed by Jekyll and turned into a corresponding .css or .js file in the final output for the static website.

This means a CoffeeScript file would have to look like this in order to get processed by Jekyll:

alert "Hello from CoffeeScript"

Your editor’s syntax highlighter might not be super-excited about the leading hyphens.

If you look at the code for large Jekyll websites out there in the wild, you’ll see that many of them drop Jekyll’s built-in asset pipeline in favor of a combination of Grunt or Gulp with Jekyll to run their builds. For a large project, this is typically the way to go because you can take advantage of the large infrastructure around these projects and get BrowserSync or LiveReload to work.

Putting It All Together

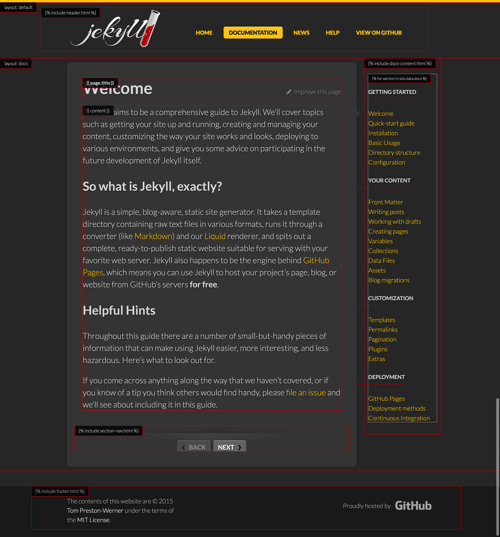

Let’s look at an actual Jekyll website to see how all of these parts fit together. What better source to learn from than the official Jekyll website. We’ll be looking at the documentation section here. You can follow along in the GitHub repository.

Here, I’ve marked roughly where all of the parts of the page come from.

The main structure of the website is defined in _layouts/default.html. There are two includes, _includes/header.html and _includes/footer.html. The header has a fairly hardcoded navigation menu. Jekyll doesn’t have a way to pull in a specific set of pages and iterate over them; so, typically, the main navigation of a website will end up being coded by hand.

Each page in the documentation section is a Markdown file in the _docs/ folder. The pages use a handy feature of Jekyll called nested layouts. The layout for the document section is set to _layouts/docs.html, and that layout in turn uses _layouts/default.html.

The navigation sidebar is generated from data in _data/docs.yml, which arranges the different files in the documentation into different groups, each with its title.

Extending Jekyll

Jekyll is quite simple to extend, and the ecosystem of plugins is fairly large. The simplest way to extend Jekyll is to add a Ruby file in the _plugins folder. There are five types of plugins: generators, converters, commands, tags and filters.

As mentioned earlier, the Liquid templating engine is strict about not allowing any code in the templates. Tags and filters work around this by enabling you to add your own tags and filters.

Generators and converters let you hook into the build process of Jekyll and generate extra pages or support new file formats.

Commands let you add new features to Jekyll’s command-line interface.

In Summary

Jekyll is widely used, and since version 2, the content model has grown rich enough to support websites with way more complexity than that of a simple blog. For a large project, you’ll probably quickly outgrow the limited asset pipeline and start relying on Gulp or Grunt. Liquid is battle-tested and a solid templating engine, but it can feel limiting. And as soon as you want to do complex filtering or querying on your content, you’ll need to write your own plugins.

Middleman

Middleman is about the same age as Jekyll. While it never got the widespread adoption that Jekyll achieved from the latter’s default integration with GitHub pages, it has quietly become the backbone of websites for some of the web’s most design-savvy companies: The websites for MailChimp, Nest and Simple are all built with Middleman.

It’s a thriving open-source project with more than a hundred contributors. The muscle behind it is Thomas Reynolds, technical director of Portland-based Instrument.

Whereas Jekyll was born of the desire for a simple, static blogging engine, Middleman was built as a framework for more advanced marketing and documentation websites. It’s a powerful tool and fast to pick up if you’re coming from the world of Rails.

Templating Engine

A stated goal of its author is to make Middleman feel like Ruby on Rails for static websites. Just as in Rails, the default templating engine is Ruby’s standard embedded Ruby (ERB) templates, but swapping these out for Haml or Liquid is straightforward.

ERB is a straightforward templating engine that lets you use free-form Ruby in your templates, with no restrictions. This gives the engine a lot more power than Liquid, but obviously it also requires more discipline on your part because you can write as much code as you want right in your templates.

Asset Pipeline

For years, the stable version of Middleman has been version 3. Now, version 4 is in beta and will bring some big changes to both the content model and the asset pipeline.

The core of Middleman’s content model is the sitemap. The site map is a list of all of the files that makes up your Middleman file, called “resources” in Middleman terminology.

Each resource has a source_file and a destination_file and gets fed through Middleman’s asset pipeline when the website is built.

A simple source/about/index.html source file would end up as a build/about/index.html destination file without any transformations. Just as when you use Rails’ asset pipeline, you can string together file extensions to specify what transformations to apply to your files.

A file named source/about/index.html.erb will get passed through the ERB templating engine and get transformed into build/about/index.html. A file named source/js/app.js.coffee would be compiled as CoffeeScript and end up as build/js/app.js.

The asset pipeline is built on Sprockets, just like Rails, which means you can use “magic” comments in your JavaScript and CSS files to include dependencies:

//= require 'includes/test.js'

This makes it easy to split your front end into small modules and have Middleman resolve the dependencies at build time.

The upcoming version 4 introduces the concept of external pipelines. These let Middleman control external tools such as Ember CLI and Webpack during the build process and makes its asset pipeline even more powerful. This is really handy for getting Middleman to spin up a separate process running Ember CLI and then proxy the right requests through to the Ember.js server.

Content Model

In your templates, you can access the site map and use Ruby to easily access, filter and sort the content.

The current stable version of Middleman (3) comes with a query interface in the site map that mimics Active Record (the object-relational mapping that powers Rails). That’s been stripped in the upcoming version 4, in favor of simple Ruby methods to query the data.

Let’s say you have a folder named source/faq. The FAQ entries are stored in Markdown files with a bit of front matter, and one looks something like this:

---

title: What is Middleman?

position: 1

---

Middleman is a [static website generator](https://www.staticgen.com) with all of the shortcuts and tools of modern web development.

Suppose you want to pull all of these entries into an ERB template and order them by position. Our imaginary source/faq.html.erb would look something like this:

<h1>FAQ</h1>

<% sitemap.resources

.select { |resource| resource.path =~ /^faq\// }

.sort_by { |resource| resource.data.position }

.each do |resource| %>

<h2 class="question"><%= resource.data.title %></h2>

<div class="answer"><%= resource.render(:layout => false) %></div>

<% end %>

Version 4 introduces the concept of collections, which let you turn those kinds of filters in the site map into a collection. When running in LiveReload mode, Middleman watches your file system and automatically update the collections (and rebuilds any file that depends on it) when something changes.

Once you get the hang of this, constructing any content architecture you might need for your website is pretty straightforward. If something can be built statically, Middleman can be made to build it for you.

There’s also support for data files (YAML and JSON files stored in a data/ folder), just like in recent versions of Jekyll.

Extending Middleman

Middleman allows extension authors to hook into different points through a powerful API. This is not needed nearly as often as it is in Jekyll, though, because the freedom to create ad-hoc helper functions, filtered collections and new pages, along with a templating engine that allows ERB, means you can do a lot out of the box that would require an extension in many other generators.

Authoring Middleman extensions is not very straightforward or well documented. To really get going, dig into some existing extensions and figure out how it’s all done.

Once you get going, however, Middleman offers hooks into both the CLI and the content model. The official directory of extensions lists a wide selection.

Roots

Like Middleman, Roots comes from an agency that needed a static website generator for its client work. Carrot, based in New York and now part of the Vice media group, sponsors the development of Roots. Jeff Escalante of Carrot is the mastermind behind it.

Whereas Middleman is like a static version of Ruby on Rails, Roots clearly comes from the world of Node.js-based front-end tools.

Roots is a lot more opinionated than Middleman, and it has obviously been tailored to make building websites with Carrot’s standard toolchain highly efficient.

Templating Engine

Roots comes with support for the Jade templating engine out of the box. Jade heavily abbreviates HTML’s syntax, cutting all of the cruft from HTML, and it makes embedding JavaScript snippets in templates clean and simple. It looks quite different from normal HTML, so copying and pasting HTML snippets from elsewhere is harder because they’ll need to be rewritten first.

You can switch the templating engine to EJS, and supporting other options wouldn’t be hard, but because Carrot has settled on Jade for its internal toolchain, all guides, examples and so on assume that you’re using Jade.

Asset Pipeline

Roots comes with a built-in asset pipeline tuned for CoffeeScript and Stylus. As with Jade for templates, you can make Roots handle other formats, but these two are what Carrot has built the workflow around, and if you go with Roots, you’ll probably have an easier time adopting the same workflow.

That being said, Roots’ asset pipeline is easily extensible. One great extension adds support for Browserify, a tool that makes it trivial to use any library distributed with npm in your front-end JavaScript. Roots’ asset pipeline also support multipass compilation. If a file is named myfile.jade.ejs, then it would be compiled with EJS first and then with Jade.

As an asset pipeline, Roots obviously doesn’t have the ecosystem you’d find around more general build tools, such as Grunt, Gulp and Brunch. However, if you don’t try to fight Roots and you adopt a workflow similar to Carrot’s, then you’ll find that it is very simple to set up and get going with, while being just powerful enough to work for most projects.

Content Model

Out of the box, Roots doesn’t really have any preference for content models. It simply takes templates in a views/ folder and turns them into HTML documents in the public/ folder. Jade makes it easy to embed Markdown, but that’s about it:

extends layout

block content

:markdown

## This Is Markdown

Everything in this block will be parsed as Markdown and inserted in the content

block within the layout.jade template.

Extending Roots

Roots doesn’t have any content model as such because it relies completely on extensions for all content, and those extensions come in many flavors.

The official directory doesn’t list as many extensions as what you’ll find for Middleman or Jekyll, but off the bat you’ll notice several for dealing with different kinds of content.

There is the Roots Dynamic Content extension, which gives you something similar to Jekyll’s collections with front matter and a Jade body. There’s also my own Roots Posts extension, which adds collections in Markdown plus front matter, just like Jekyll.

The Records and YAML extensions add support for data files that can be pulled into any template. The former will even fetch data from any URL and make it available from the templates.

A similar extension is Roots Contentful, which Carrot blogged about in its article “Building a Static CMS.” The extension pulls in content from Contentful’s API and lets you filter and iterate over it.

Getting started with writing Roots extensions is very easy, and the documentation has a really good introduction to how the different hooks and compilation passes work. More thorough documentation on the inner workings of Roots wouldn’t hurt, though.

Fortunately, there is a very active Gitter chat room, where both Jeff Escalante and other Roots contributors readily answer questions.

Hugo

Hugo is a much more recent addition to the world of static website generators, having started just two years ago. It’s certainly growing the fastest in popularity at the moment.

Hugo is written in Go, which makes it the only really popular generator written in a statically compiled language. Most of its big advantages, and largest drawback, come from this fact.

Let’s start with the good. Hugo is fast! Not just fast as in, “This is pretty cool.” Fast as in, “Whoa! This feels like more than 1G acceleration!”

A great benchmark on YouTube shows Hugo building 5000 pages in about 6 seconds, and PieCrust2’s author, Ludovic Chabant, has a blog post that puts these numbers into context, showing Hugo generating a sample website about 75 times faster than Middleman.

Hugo is also incredibly simple to install and update. Ruby and Node.js are fine if you’ve already set up a development environment; otherwise, you’re in for a lot of pain. Not so with Hugo: Just download the binary for your platform and run it — no runtime dependencies or installation process. Want to update Hugo? Just download a new binary and you’re set.

Templating Engine

Hugo uses the package template (html/template) from Go’s standard library, but it also supports two alternative Go-based template engines, Amber and Ace.

The package template engine is similar to Liquid in that it allows a limited amount of logic in your templates. As with Liquid, this is both a blessing and a curse. It will make your templates simpler and usually cleaner, but obviously it makes you far more dependent on whatever functions the templating language provides.

Fortunately, Hugo provides a really well-conceived set of helper methods that make it easy to do custom filtering, sorting and conditionals.

There’s no concept of layouts in the package template as we see in Jekyll, Roots and Middleman — just partials.

Variables and functions are inserted via curly braces:

<h1>{{ .Site.Title }}</h1>

One really interesting aspect of the package template engine is that variable insertion is context-aware, so the engine will always escape the output according to the context you’re in. So, the same output would be escaped differently according to whether you’re in an HTML block, within the quotes of an HTML attribute or in a <script> tag.

Asset Pipeline

This is one of Hugo’s big weaknesses. You’d better want to work with plain CSS and JavaScript, or integrate an external asset pipeline with a tool like Gulp or Grunt, because Hugo doesn’t include any kind of asset pipeline.

When Hugo builds your website, it copies any files in the static folder to your build directory, but that’s it. Want Sass, EcmaScript6, CSS auto-prefixing and so on? You’ll have to set up an external build tool and make Hugo part of a build process (which negates many of the advantages of having just one static binary to install).

Hugo does come with LiveReload built in. If you can do with no-frills CSS and JavaScript, that might be all you need.

Extensions

Because Go is a statically compiled binary and Hugo is distributed as a single compiled file, there is no easy way to add a plugin or extension engine to Hugo.

This means you’ll need to rely exclusively on the features built into Hugo, rather than roll your own. In this way, Hugo is almost the exact opposite of Roots, which is almost nothing on its own without plugins.

Fortunately, Hugo comes with batteries included and packs a big punch out of the box. Shortcodes, dynamic data sources, menus, syntax highlighting and tables of contents are all built into Hugo, and the templating language has enough options to sort and filter content. So, a lot of the cases for which you would otherwise want plugins or custom helpers are already taken care of.

The closest you’ll come to an extensions engine in Hugo are the external helpers, which currently add support for the AsciiDoc and reStructuredText formats, in addition to Markdown. But there’s no real way for these external helpers to interact with Hugo’s templating engine or content model.

Content Model

With the bad parts behind us — no asset pipeline, no extensions — let’s get back to the good stuff.

Hugo has the most powerful content model out of the box of any of the static website generators.

Content is grouped into sections with entries. Sections can be nested as a tree:

└── content

├── post

| ├── firstpost.md // <- https://1.com/post/firstpost/

| ├── happy

| | └── ness.md // <- https://1.com/post/happy/ness/

| └── secondpost.md // <- https://1.com/post/secondpost/

└── quote

├── first.md // <- https://1.com/quote/first/

└── second.md // <- https://1.com/quote/second/

Here, post, post/happy and quote would be sections, and all of the Markdown files would be entries. As with most other static website generators, entries may have meta data encoded as front matter. Hugo lets you write front matter in YAML, JSON or TOML.

Content from different sections can easily be pulled into templates, filtered and sorted. And the command-line tool makes it easy to set up boilerplates for different content types, to make writing posts, quotes and so on easy.

Here’s a condensed version of a short real-life snippet from Static Web-Tech that pulls in the three most recent entries from the “Presentations” section:

<ul class="link-list recent-posts">

{{ range first 3 (where .Site.Pages.ByDate "Section" "presentations")}}

<li>

<a href="{{ .Permalink }}">{{ .Title }}</a>

<span class="date">{{ .Params.presenter }}</span>

</li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

The range and where syntax with various filters takes a little getting used to. But once it clicks, it’s very powerful.

The same could be said for Hugo’s taxonomy, which adds support for both tags and categories (with their own pages — so, you could list all posts in a category, list all entries with a particular tag, etc.) and helpers for showing counts, listing all tags and so on.

Apart from this, Hugo can also get content from data files and load data dynamically from URLs during the build process.

Modern Static Website Technology

While static websites have been around since the beginning of the Internet, modern static website generation is just getting started.

All of the generators reviewed above are powerful modern tools that have already been used by large agencies to develop big, complex websites. They are all under active development and will only get more powerful and more flexible.

The whole ecosystem around modern static website technology is growing rapidly, with an emerging array of external services for hosting, search, e-commerce, commenting and similar functionality. The limit of what you can achieve with a static website keeps getting pushed.

If you’re a beginner, one tricky question is simply where to start. The answer will generally depend on what programming language you’re familiar with and whether you’re more of a designer or a developer:

- Jekyll is a safe choice as long as you’re familiar with the whole Ruby toolchain and you use Mac or Linux. (Ruby’s ecosystem is not very Windows-friendly.)

- Middleman has broad appeal to anyone coming from the world of Rails. It’s geared to people who are comfortable writing Ruby, and it is a better fit than Jekyll for large websites with a lot of sections and a complex content configuration.

- Roots is great for front-end developers who are comfortable with JavaScript (or CoffeeScript) and want to build custom-designed websites.

- Hugo is great for content-driven websites, because it is completely dependency-free and is easy to get going. What it lacks for in extensibility, it largely makes up for with a good content model and super-fast build times.

Use, share, improve, enjoy. Welcome to modern static website technology!

Further Reading

- Using A Static Site Generator At Scale: Lessons Learned

- Build A Blog With Jekyll And GitHub Pages

- Content Modeling With Jekyll

- Creating Websites With Dropbox-Powered Hosting Tools

Enterprise UX Masterclass, with Marko Dugonjic

Enterprise UX Masterclass, with Marko Dugonjic

Register For Free

Register For Free

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding. Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial