The Art Of The Intercept: Moving Beyond “Would You Like To Take A Survey?”

Maxwell is a researcher at a design firm that is working on a mobile payment app. He wants to learn more about how users currently interact with point-of-sale terminals. Maxwell contacts a local grocery store to coordinate times to observe customers as they are checking out. He then asks every fifth customer who checks out to complete a brief survey. Maxwell is engaging in intercepts as part of his recruitment of research participants.

We often want information on what users and potential users of our designs think and how they behave in the context of where they will use our design. For example, if you are designing a new interface for an ATM, you would benefit from understanding how current users engage with ATMs in the context of spaces where ATMs are located.

Intercepts allow you to engage users in a variety of settings to collect data to inform your design. It sounds simple, but there is a right way to ask people to stop and participate in a study. This article shares a method to design and carry out effective intercepts as part of your user research.

What Is An Intercept?

An intercept entails approaching people who are engaged in an activity to get their feedback. Intercepts are not a research method – you need to pair them with a research method, such as interviewing or observation. First, you identify a potential participant, then you gain their permission to participate in research, and then you administer the interview or observe them engaging with a prototype. Intercepts themselves do not provide data; they provide participants to give you data.

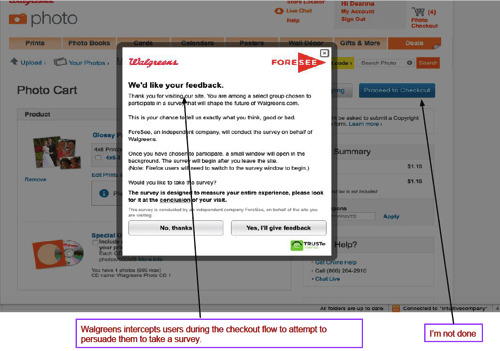

Most of us are familiar with the concept of an intercept, particularly online. Online intercepts often consist of an annoying popup asking you to provide feedback on the website you are currently using (see screenshot below). They’re useful for seeking feedback from users engaging in an activity online. They are also passive and subject to the most extreme (pleased or displeased) users taking the time to complete them. This article is about in-person, public intercepts – or real-life annoying popups.

Why Should You Intercept?

Intercepts are useful for connecting with real participants who can provide you with real data. You can pair many research methods with them as users engage in an activity. Additionally, you can conduct them in a variety of settings. For example, you could use them to gather people to:

- Test a prototype of a seat-locator app as concert-goers are waiting in line at a venue.

- Complete interviews about the experience of waiting in line at a bank as customers are waiting in line at a bank.

- Complete surveys on patrons’ level of engagement with and enjoyment of a new touchscreen kiosk at a museum as they are exiting the exhibit area.

- Engage in a card sort for the main navigation of a medical group’s online portal for patients while the patients are in the waiting room (non-emergency cases, of course!).

- Engage in usability testing of an iPad app that presents real-time horse-racing results as you observe participants using it in the grandstand of a racetrack.

The Benefits Of Recruitment Using Intercepts

You can see from the examples that the benefits include the following:

- The context of the task is top of mind.

- You can speak with people before, during or after they have had a particular experience with your product’s design.

- You can observe behavior and then ask people about what they were doing.

- You could reach a large number of people in a short period of time if you are at a crowded venue.

- Unlike online intercepts, you can ask follow-up questions as you are engaged with participants.

- Such recruitment might be cheaper than other methods, such as paying for a sample. I often offer small tokens of appreciation to people who agree to participate in a study in a public place. These tokens of appreciation cost nowhere near the several thousands of dollars I’ve paid recruitment firms to provide a panel of participants for interviews or usability testing.

The Drawbacks Of Recruitment Using Intercepts

Be aware of the potential drawbacks of using the technique to recruit participants for a study. One initial drawback is that you will often need permission to conduct intercepts. If you are identifying customers after they have used the ATM in a bank’s lobby, you will need the bank’s permission. If you are working with train passengers as they ride to their destination, you’ll need the train operator’s permission. You will likely be removed from the property of any private place if you attempt recruitment without permission – and rightfully so.

Here are additional drawbacks, along with examples:

- You might have difficulty finding a large number of participants if you are in an area with low foot traffic. For example, you won’t find many people visiting a bank after 6pm on a Thursday.

- You might not find the participants you are looking for as easily as if you had paid to recruit them. For example, if you are looking for adults with children under the age of 10, you would have to visually identify these people or risk wasting time asking each adult if they meet this criterion.

- Someone needs to be present at all times. You cannot interrupt people passively in the way that online intercepts allow. For example, very few people will walk up to an unstaffed table and sit down to complete a study. Some people will, which I’ve experienced first hand, but most people won’t.

How To Intercept People – Steps 1–5: Preparation

I have years of experience asking thousands of people to participate in studies, particularly in art museums, nature centers, science centers and zoos. Intercepts are often associated with what some have termed guerrilla research – research methods you can do quickly and cheaply (see the additional resources at the end). I have done guerilla research in front of gorillas, manatees, alligators and paintings by Monet and Degas. I also instruct an introductory course on UX research methods that culminates in an intercept activity. Consult with a user researcher, and be sure to account for the following steps when setting up a study that involves intercepting participants.

1. Determine Research Method And Create Research Instrument

What exactly are you going to ask people to do when you talk to them? Examples of relevant methods include card sorting, interviewing, observation, prototyping, surveys and usability testing. You don’t need to worry about intercepts if you’re conducting a competitive analysis or a heuristic assessment. Once you know that intercepts are appropriate for your research method, move to step two.

2. Determine Exact Location(s)

Consider the activity you want potential participants to engage in. Ideas include standing in the vicinity of an Apple store to interview folks about using a smartphone app; or standing outside a bank to ask participants to discuss their online banking behavior.

Also, consider what you will ask people to do. You wouldn’t want to carry a prototype of a touchscreen kiosk to various locations. You’d want to pick a place where people will come to you. What other supplies will you need on hand for the day? Do you need a large space for your supplies, or can everything fit in your pockets? This will help you determine where to find people for your study.

3. Secure Permission

I’m not familiar enough with local laws to give you advice on when you need permission. If you plan to stand in someone’s shop or on their property, you must seek their permission. I always work directly with a venue when I conduct intercepts on site. This allows me to receive an identification badge and introductions to key security staff so they know I’m on the grounds speaking to visitors for the day.

You won’t always have the luxury of a preexisting relationship with the venue where you want to meet people. Always get written permission to be on site if you are conducting intercepts in a privately owned setting, such as a shop or a zoo. Consider inviting the venue to add a question or two to your survey or interview in exchange for permission to talk to people on their site. For example, you could ask people how satisfied they are with their visit to the venue and what contributed to their level of satisfaction. This would provide a benefit to the venue in exchange for letting you intercept visitors. You could share the responses with the venue, and visitors will get the impression that the venue wants their feedback on their experience.

If what you are studying would be of interest to the venue, you could offer to share your findings with them.

Most venues won’t have a problem with you talking to visitors, as long as you are respectful and they see value in what you are doing.

4. Create A Discussion Guide

How you approach potential study participants is critical. You won’t find many people willing to stop if you run up to them and ask, “Would you like to take part in a survey?”

Your discussion guide should cover the following:

- Introducing yourself: “Hi, I’m Victor.”

- What you are doing: “I’m conducting a survey of iPhone users in the park.”

- Your objective: for example, “To inform the design of a new iPhone app for park users.”

- Asking the person if they are willing to participate: “Are you willing to provide me with some feedback?”

- How much time you estimate this will take: “I’ll need only about 15 minutes of your time.”

- What incentives you’re offering: “Your name will be entered in a draw for free tickets to ‘Spiderman on Ice’ if you complete the survey.”

I don’t recommend offering an incentive if you expect to take less than 15 minutes of a person’s time. If you plan to ask people to spend 15 or more minutes of unplanned time with you, you will probably encounter difficulty in getting them to participate without an incentive. Incentives could include cash, a gift card, entry in a prize draw, or free tickets to a venue or event.

Mention the incentive after your introduction. The person should first hear what you are asking them to do and then think about the incentive. If you present the incentive up front, you risk highlighting the incentive as the main reason to participate. If you wait to mention the incentive until after the potential participant has accepted or declined your request, then you will have waited too long for the incentive to have any affect on their participation.

Keep in mind that the incentive might skew participation in your study, so if possible try to reduce the need for an incentive. Ultimately, you will need to weigh participation being skewed toward those who want the incentive on the one hand, with the time it takes to complete the interview on the other.

I always recommend offering a token of appreciation. (See the section “Notes And Tips On Conducting Intercepts” for more on this.)

5. Read Introduction Aloud And Edit

Often, what we initially write out on paper doesn’t sound as smooth or coherent as how it sounds in our heads. I always advise reading aloud to others to make sure that what you’ve written is easily understood. Find people who are not involved in the project, because they will be less familiar with the topic.

How To Intercept People – Steps 6–8: Conducting The Intercepts

The following steps apply when you are on the ground and ready to intercept.

6. Set Up The Area

Your needs will depend on the type of study you are conducting. You might need a table and chairs if you are doing 15-minute interviews and don’t want people to stand for that long. You might need a space to set up a prototype for people to engage with. You might want to set up near an exit where you know people will have completed an activity.

Make sure to have plenty of pens, a clipboard or computer tablet, and copies of your research protocol as needed. You might also need other supplies throughout the time you are identifying people. Usually, the fewer supplies you need to manage your space, the better.

I strongly advise that you stand or sit away from any table or area you have set up to conduct the study. You do not want to be stationary and unable to step up to people to engage them in conversation. People will avoid you if they see you sitting at a table eagerly staring at them with the hope-filled look of a researcher. Standing and approaching potential participants is best.

7. Select Participants

You might think it will be tough to choose who to stop. People are busy – some people look grumpy, some look distracted, and some look rushed. Your job isn’t to visually determine who will stop or not. You will end up only stopping people whom you visually identify as nice people who have the time to participate in a study. No one looks like that in real life. Here is how to recruit participants:

- Pick a number from one to five.

- Wherever you are set up, draw an imaginary line in the ground, perhaps at the entrance or midpoint of the space you are in, somewhere you can easily stand.

- If you picked, say, the number three, intercept every third person who crosses that imaginary line.

When someone agrees to participate, work with them until you are able to return to your post. You would then begin intercepting every third person again. If someone refuses to participate, thank them and then stop the third person who crosses your line after that.

This method helps you to avoid any personal bias about who you think will or won’t stop for the study.

You can use this same method if you are approaching people who are in a line or standing around waiting for something. Start with the first person in line and count every, say, third person and ask them to participate.

I strongly recommend using a process like this to randomly approach people. This will increase the validity of your findings compared with a study in which you have only spoken to people whom you feel comfortable approaching. I have used this method in my dissertation and in a number of published academic studies. The review board for my university approved this method as being aligned with best practices.

If you don’t want to select a random number, then I would suggest engaging in the process as described, but choose the very next person who crosses the imaginary line each time. So, unless you are actively working with a participant, you would ask everyone who passes by to participate. The point is that you need to reduce bias by not choosing who to approach based on judgment.

8. Administer Research Method

If someone agrees to stop and participate, be ready to engage them immediately. If you are conducting an interview, have the protocol ready on your clipboard or tablet, and begin asking the questions you have prepared. If you are conducting a survey and participants are supposed to complete the questionnaire alone, hand them the clipboard or tablet, and then get another clipboard or tablet to recruit someone else. If you are prototyping, bring the participant to your station and ask them to engage with the prototype.

Account for each of these steps when planning a study, and add steps or tweak these steps as needed.

Notes And Tips On Conducting Intercepts

Deal With Rejection

People will tell you they do not want to participate. People will run past you before you can even ask them to participate. People might even say unfriendly things to you. This is almost never a reflection on you. We live in an over-researched world. If you find that many people are saying no, take a break and recalibrate yourself. Look closely at what you are saying to and asking of them. For example, asking people on the spot to spend 30 minutes giving feedback isn’t realistic. Consider recruiting in another way so that people know the time required beforehand.

Secure Permission To Work With Children

You expose yourself to a number of potential liability issues when you work with populations that are not able to legally make their own decisions. At a minimum, you will need to secure parental permission if you want to recruit children into your study. You will also need to allow a parent to be present for the entire time you are with the child. Contact an institutional review board for further guidance if you need to conduct research with children.

Accommodate Groups With Children

Even if you do not want to conduct research with children, you might still want to speak to people who have children with them. You should be able to accommodate children. Prepare material for children to engage with while the parent is busy, such as coloring books, puzzles or magazines.

Alternate Days And Times If Possible

You might find different types of people in a given location, depending on the time of day or day of the week. You’re not going to find many full-time working professionals in a park at 2pm on a weekday, but you are very likely to find them there on a weekend afternoon. Spread out the times and days that you intercept people for a study.

Offer Tokens Of Appreciation

You build goodwill by offering a small token of appreciation to people who agree to participate. You could provide a discount coupon for your product, a small item from a gift shop (such as a postcard or stickers) or an entry in a prize draw. This is not about compensation, but rather about a concrete way to thank them for spending time with you. You are doing the next researcher a favor by treating participants with respect.

Use Multiple Researchers When Possible

You increase your efficiency when more than one researcher is intercepting. If you have a survey that people will self-administer, you can double the number of participants by having two researchers. Each researcher can cover a different area and then hand participants the survey once they have agreed to participate.

I also recommend using multiple researchers if you are conducting interviews, which will reduce the workload. You can take turns approaching people and conducting the interview. Whoever is intercepting can get a participant to agree and then introduce them to the interviewer. The interceptor would then take notes for the duration of the interview. Another option is for the interceptor to continue recruiting and ask willing participants to do a short activity while they wait for the interviewer to become free. Or both of you could both intercept and interview.

Exit Intercepts

Intercepting people at an exit or on completing an activity might be especially difficult. If so, I suggest two options. Request as little of their time as possible, five minutes or less. If that isn’t an option, then try recruiting people at the beginning of the task or as they enter the area. You can tell them you are interested in getting their feedback when they complete the activity or at the end of their visit. This will help them to budget time to speak with you once they are finished. Two researchers are especially helpful with this technique, one to stand at the entrance and one to reengage with people at the exit. Yes, some people will agree to help you at the entrance and then avoid you at the exit, but you stand to gain a lot more participants if they are aware they can help you than if you hold off and make it a surprise.

International Research

The method presented here is one I’ve only used in the United States. Different cultures and countries have different social norms and expectations that I have not accounted for. Here are some recommendations if you are considering intercepts in another country:

- Always respect the cultural and social norms of the location where you are collecting data.

- Consider hiring local data collectors who are culturally sensitive.

- Translate your words using a professional translator, and double-check with locals to make sure that what you are saying will come across well. If you are not familiar with the native language, hire a native speaker to conduct the intercepts.

- Use another method to recruit participants if approaching strangers would violate cultural norms.

- Learn more in resources such as International User Research by Chui Chui Tan.

Case Study: A Smartphone App For Zoo Visitors

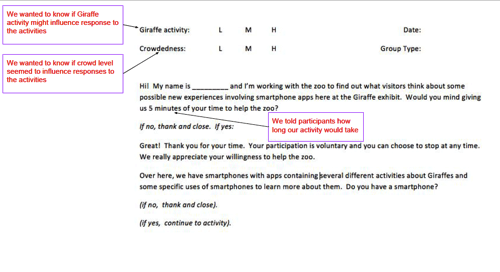

I conducted intercepts with zoo visitors for a project in which we were designing apps for certain zoo exhibits. The project’s team wanted to know more about how visitors were currently using their phones while visiting the zoo, particularly in the exhibit areas for which apps were going to be created.

A colleague and I designed a study to gain feedback from zoo visitors. We knew we wanted to observe how visitors were currently using their phones in the exhibit area. We also wanted to test prototypes of the apps inside the exhibits. Because we wanted to know more information about zoo visitors’ attitudes and behaviors in the context of specific zoo exhibits, we chose to intercept visitors when they were in these exhibit areas.

Zoo visitors are busy. They don’t budget time to participate in research during a visit; so, we wanted the intercept’s introduction to be brief. We worked with the project’s team to create a concise script:

We chose to conduct intercepts on a weekend (Friday through Sunday). These are the busiest days for zoos. On the days of the study, we set up a table with our supplies in the exhibit area. The zoo was located in a tropical climate, which required us to have bottles of water on hand to stay hydrated. We also carried plastic boxes in which to keep our forms and phones, and umbrellas in case of rain.

We decided to stop every third visitor who crossed a line near the end of the exhibit area. We stood near the exit so that we could observe visitors and intercept them without having to chase them down. Once visitors agreed to participate, we immediately asked them questions about their mobile phone usage, eliminating visitors who did not have a smartphone. Visitors with smartphones completed various activities with a prototype app. We thanked visitors who did not own a smartphone for their time and did not ask them to complete the rest of the study.

We gave animal-print pencils with the zoo’s logo to visitors for completing our study. We did not make visitors aware they would receive the token of appreciation before completing the study. The cost of the pencils, which we bought from the zoo’s gift shop, was a fraction of what a recruitment firm would have cost us.

We successfully intercepted 60 visitors over the course of a weekend. This was our target number. We were also able to observe participants and non-participants as they engaged with the exhibit. We noted how many people were using phones as they interacted with the exhibit. We found that many visitors took pictures and texted while they stood in the exhibit area. We made a number of recommendations to the project’s design team based on what we observed and on the data we collected from the prototypes that weekend.

Our findings from the study helped the team make critical decisions about the design of the app. For example, we noted that visitors would often use their phones to take pictures of the people they came with and would share their phone with them. We recommended adding activities to the app that would facilitate in-group sharing at the exhibit, such as a fun and educational task.

We would not have been able to make the connections between our observations and the data we collected from visitors on site if we had not engaged in intercepts. We would not have been able to intercept 60 visitors over the course of a weekend if we hadn’t set them up in a way that was comfortable for visitors in a zoo setting.

Take It To The Streets

You can use the steps and information provided in this article in your own process for intercepting users. As we continue to engage our audiences in research, we will need to find creative ways to get feedback. Intercepts will remain a primary method of acquiring research participants. The benefits usually outweigh the costs, and we are able to access participants in a variety of settings. Try developing a script with some of your colleagues, practice intercepting each other, and then take what you’ve got out in public and find some participants.

Additional Resources On Guerrilla Research

- “Getting Guerrilla With It,” Russ Unger and Todd Zaki Warfel, UX Magazine

- “Guerrilla Research Tactics and Tools,” Christopher Myhill, UX Booth

Further Reading

- Using Social Media For User Research

- How To Run User Tests At A Conference

- The UX Research Plan That Stakeholders Love

- A 5-Step Process For Conducting User Research

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding. Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial Register For Free

Register For Free

Smart Interface Design Patterns, 45 lessons + UX training

Smart Interface Design Patterns, 45 lessons + UX training