Filling Up Your Tank, Or How To Justify User Research Sample Size And Data

Introduction

Researchers must justify the sample size of their studies. Clients, colleagues and investors want to know they can trust a study’s recommendations. They base a lot of trust on sample population and size. Did you talk to the right people? Did you talk to the right number of people? Researchers must also know how to make the most of the data they collect. Your sample size won’t matter if you haven’t asked good questions and done thorough analysis.

Quantitative research methods (such as surveys) come with effective statistical techniques for determining a sample size. This is based on the population size you are studying and the level of confidence desired in the results. Many stakeholders are familiar with quantitative methods and terms such as “statistical significance.” These stakeholders tend to carry this understanding across all research projects and are, therefore, expecting to hear similar terms and hear of similar sample sizes across research projects.

Qualitative researchers need to set the context for stakeholders. Qualitative research methods (such as interviews) currently have no similar commonly accepted technique. Yet, there are steps you should take to ensure you have collected and analyzed the right amount of data.

In this article, I will propose a formula for determining qualitative sample sizes in user research. I’ll also discuss how to collect and analyze data in order to achieve “data saturation.” Finally, I will provide a case study highlighting the concepts explored in this article.

Qualitative Research Sample Sizes

As researchers, or members of teams that work with researchers, we need to understand and convey to others why we’ve chosen a particular sample size.

I’ll give you the bad news first. We don’t have an agreed-upon formula to determine an exact sample size for qualitative research. Anyone who says otherwise is wrong. We do have some suggested guidelines based on precedent in academic studies. We often use smaller sample sizes for qualitative research. I have been in projects that include interviews with fewer than 10 people. I have also been in projects in which we’ve interviewed dozens of people. Jakob Nielson suggests a sample size of five for usability testing. However, he adds a number of qualifiers, and the suggestion is limited to usability testing studies, not exploratory interviews, contextual inquiry or other qualitative methods commonly used in the generative stages of research.

So, how do we determine a qualitative sample size? We need to understand the purpose of our research. We conduct qualitative research to gain a deep understanding of something (an event, issue, problem or solution). This is different from quantitative research, whose purpose is to quantify, or measure the presence of, something. Quantification usually provides a shallow yet broad view of an issue.

You can determine your qualitative research sample size on a rolling basis. Or you can state the sample size up front.

If you are an academic researcher in a multi-year project, or you have a large budget and generous timeline, you can suggest a rolling sample size. You’d collect data from a set number of participants. At the same time, you’d analyze the data and determine whether you need to collect more data. This approach leads to large amounts of data and greater certainty in your findings. You will have a deep and broad view of the issue that you are designing to address. You would stop collecting data because you have exhausted the need to continue collecting data. You will likely end up with a larger sample size.

Most clients or projects require you to state a predetermined sample size. Reality, in the form of budget and time, often dictates sample sizes. You won’t have time to interview 50 people and do a thorough analysis of the data if your project is expected to move from research to design to development over an 8- to 10-week period. A sample size of 10 to 12 is probably more realistic for a project like this. You will probably have two weeks to get from recruitment to analysis. You would stop because you have exhausted the resources for your study. Yet our clients and peers want us to make impactful recommendations from this data.

Your use of a rolling or predetermined sample size will determine how you speak about why you stopped collecting data. For a rolling sample, you could say, “We stopped collecting data after analysis found it would no longer prove valuable to collect more data.” If you use a predetermined sample size, you could say, “We stopped collecting data after we interviewed (or observed, etc.) the predetermined number we agreed upon. We fully analyzed the data collected.”

We can still maintain a rigorous process using a predetermined sample size. Our findings are still valid. Data saturation helps to ensure this. You need to complete three steps in order to claim you’ve done due diligence in determining a sample size and reaching data saturation when using a predetermined sample:

- Determine a sample sized based on meaningful criteria.

- Reach saturation of data collection.

- Reach saturation of data analysis.

I will cover each step in detail in the following sections.

Determining A Sample Size: From Guidelines To A Formula

Donna Bonde from Research by Design, a marketing research firm, provides research-based guidelines (Qualitative market research: When enough is enough) to help determine the size of a qualitative research sample up front. Bonde reviewed the work of numerous market research studies to determine the consistent key factors for sample sizes across the studies. Bonde considers the guidelines not to be a formula, but rather to be factors affecting qualitative sample sizes. The guidelines are meant for marketing research, so I’ve modified them to suit the needs of the user researcher. I have also organized the relevant factors into a formula. This will help you to determine and justify a sample size and to increase the likelihood of reaching saturation.

Qualitative Sample Size Formula

The formula for determining a sample size, based on my interpretation of Research by Design’s guidelines, is: scope × characteristics ÷ expertise + or - resources.

Here are descriptions and examples for the four factors of the formula for determining your qualitative sample size.

1. Scope Of The Investigation

You need to consider what you are trying to accomplish. This is the most important factor when considering sample size. Are you looking to design a solution from scratch? Or are you looking to identify small wins to improve your current product’s usability? You would maximize the number of research participants if you were looking to inform the creation of a new experience. You could include fewer participants if you are trying to identify potential difficulties in the checkout workflow of your application.

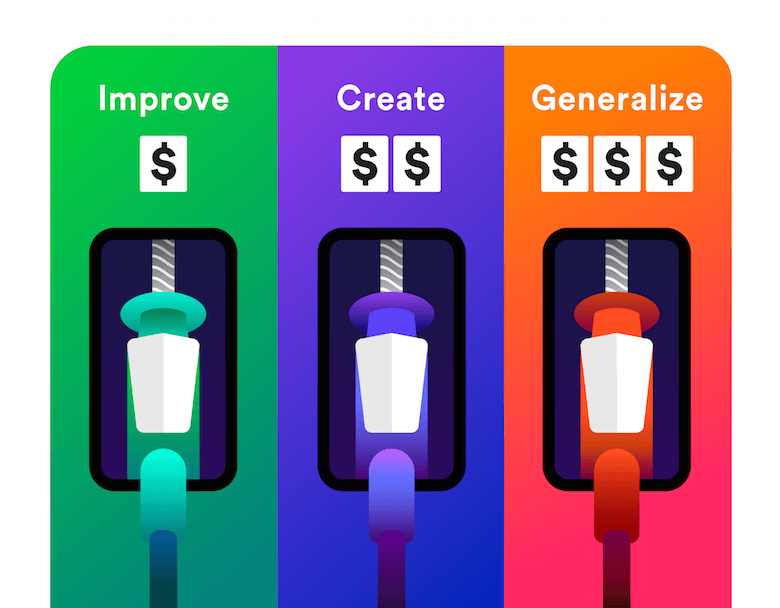

Numerically, the scope can be anywhere from 1 to infinity. A zero would designate no research, which violates principles of UX design. You will multiply the scope by each user type × 3 in the next step. So, including a number greater than 1 will drastically increase your sample size. Scope is all about how you want to apply your results. I recommend using the following values for filling in scope:

- research looking at an existing product (for example, usability testing, identifying new features, or studying the current state);

- creating a new product (for example, a new portal where you will house all applications that your staff use);

- generalizing beyond your product (for example, publishing your study in a research journal or claiming a new design process).

I’ve given you guidelines for scope that will make sure your sample size is comparable to what some academic researchers suggest. Scholar John Creswell suggests guidelines ranging from as few as five for a case study (for example, your existing product) to more than 20 for developing a new theory (for example, generalizing beyond your product). We won’t stop with Creswell’s recommendations because you will create a stronger argument and demonstrate better understanding when you show that you’ve used a formula to determine your sample size. Also, scholars are nowhere near agreement on specific sample sizes to use, as Creswell suggests.

2. Characteristics Of The Study’s Population

You will increase your sample size as the diversity of your population increases. You will want multiple representatives of each persona or user type you are designing for. I recommend a minimum of three participants per user type. This allows for a deeper exploration of the experience each user type might have.

Let’s say you are designing an application that enables manufacturing companies to input and track the ordering and shipment of supplies from warehouses to factories. You would want to interview many people involved in this process: warehouse floor workers, office staff, procurement staff from the warehouse and factory, managers and more. If you were looking only to redesign the interface of the read-only tracking function of this app, then you might only need to interview people who look at the tracking page of the application: warehouse and factory office workers.

Numerically, C = P × 3, where P equals the number of unique user types you’ve identified. Three user types would give you C = 9.

3. Expertise Of The Researchers

Experienced researchers can do more with a smaller sample size than less experienced researchers. Qualitative researchers insert themselves into the data-collection process differently than quantitative researchers. You can’t change your line of questioning in a survey based on an unforeseen topic becoming relevant. You can adjust your line of questioning based on the real-time feedback you get from a qualitative research participant. Experienced researchers will generate more and better-quality data from each participant. An experienced researcher knows how and when to dig deeper based on a participant’s response. An experienced researcher will bring a history of experiences to add insight to the data analysis.

Numerically, expertise (E) could range from 1 to infinity. Realistically, the range should be from 1 to 2. For example, a researcher with no experience should have a 1 because they will need the full size of the sample, and they would gain experience as the project moves forward. Using a 2 would halve your sample size (at that point in the formula), which is drastic as well. I’d suggest adding tenths (.10) based on 5-year increments; for example, a researcher with 5 years of experience would give you E = 1.10.

4. Resources

An unfortunate truth, you will have to account for budget and time constraints when determining a sample size. You will need to increase either your timeline or the number of researchers on a project, as you increase the size of your sample. Most clients or projects will require you to identify a set number of research participants. Time and money will affect this number. You will need to budget time for recruiting participants and analyzing data. You will also need to consider the needs of design and development for completing those duties. Peers will not value your research findings if the findings come in after everyone else has moved forward. I recommend scaling down a sample size to get the data on time, rather than hold on to a sample size that causes your research to drag on past when your team needs the findings.

Numerically, resources will be a number from N (i.e. the desired sample size) - 1 or more to + 1 or more. You’ll determine resources based on the cost and time you will spend recruiting participants, conducting research and analyzing data. You might have specific numbers based on previous efforts. For example, you might know it will cost around $15,000 to use a recruitment service, to rent a facility for two days and to pay 15 participants for one-hour interviews. You also know the recruiting service will ask for up to three weeks to find the sample you need, depending on the complexity of the study. On the other hand, you might be able to recruit 15 participants at no extra cost if you ask your client to find existing users, but that might add weeks to the process if you can’t find them quickly or if potential participants aren’t immediately available.

You will need to budget for the time and resources necessary to get the sample you require, or you will need to reduce your sample accordingly. Because this is a fact of life, I recommend being up front about it. Say to your boss or client, “We want to speak to 15 users for this project. But our budget and timeline will only allow for 10. Please keep that in mind when we present our findings.”

Using The Formula: An Example

Let’s say you want to figure out how many participants to include in a study that is assessing the need to create an area for customer-service staff members of a mid-sized client to access the applications they use at work (a portal). Your client states that there are three basic user types: floor staff, managers and administrators. You have a healthy budget and a total of 10 weeks to go from research to presentation of design concepts for the portal and a working prototype of a few workflows within the portal. You have been a researcher for 11 years.

Your formula for determining a sample size would be:

scope (S) large scope - creating a new portal (S) = 2;characteristics (C) - 3 user types (C) = 9;expertise (E) - 11 years (E)= 1.20;resources (R) - fine for this study (R) = 0;our formula is ((SxC)/E) + R;- So,

((2x9)/1.2) + 0 = 15participants for this study.

Data Saturation

Data saturation is a concept from academic research. Academics do not agree on the definition of saturation. The basic idea is to get enough data to support the decisions you make, and to exhaust your analysis of that data. You need to get enough data in order to create meaningful themes and recommendations from your exhaustive analysis. Reaching data saturation depends on the particular methods you are using to collect data. Interviews are often cited as the best method to ensure you reach data saturation.

Researchers do not often use sample size alone as the criterion for assessing saturation. I support a two-pronged definition: saturation of data collection and saturation of data analysis. You need to do both to achieve data saturation in a study. You also need to do both, data collection and analysis, simultaneously to know you’ve achieved saturation before the study concludes.

Saturation Of Data Collection

You would collect enough meaningful data to identify key themes and make recommendations. Once you have coded your data and identified key themes, do you have actionable takeaways? If so, you should feel comfortable with what you have. If you haven’t identified meaningful themes or if the participants have all had many different experiences, then collect additional data. Or if something unique came up in only one interview, you might add more focused interviews to further explore that concept.

You would achieve saturation of data collection in part by collecting rich data. Rich data is data that provides a depth of insight into the problem you are investigating. Rich data is an output of good questions, good follow-up prompts and an experienced researcher. You would collect rich data based on the quality of the data collection, not the sample size. It’s possible to get better information from a sample of three people whom you spend an hour each interviewing than you would from six people whom you only spend 30 minutes interviewing. You need to hone your questions in order to collect rich data. You would accomplish this when you create a questionnaire and iterate based on feedback from others, as well as from practice runs prior to data collection.

You might want to limit your study to specific types of participants. This could reduce the need for a larger sample to reach saturation of data collection.

For example, let’s say you want to understand the situation of someone who has switched banks recently.

Have you identified key characteristics that might differentiate members of this group? Perhaps someone who recently moved and switched banks has had a drastically different experience than someone whose bank charged them too many fees and made them angry.

Have you talked to multiple people who fit each user type? Did their experiences suggest a commonality between the user types? Or do you need to look deeper at one or both user types?

If you interview only one person who fits the description of a user who has recently moved and switched banks, then you’d need to increase your sample and talk to more people of that user type. Perhaps you could make an argument that only one of these user types is relevant to your current project. This would allow you to focus on one of the user types and reduce the number of participants needed to reach saturation of data collection.

Saturation Of Data Collection Example

Let’s say you’ve determined that you’ll need a sample size of 15 people for your banking study.

You’ve created your questionnaire and focused on exploring how your participants have experienced banking, both in person and online, over the past five years. You spend an hour interviewing each participant, thoroughly exhausting your lines of questioning and follow-up prompts.

You collect and analyze the data simultaneously. After 12 interviews, you find the following key themes have emerged from your data:

- users feel banks lack transparency,

- users have poor onboarding experiences,

- users feel more compelled to bank somewhere where they feel a personal connection.

Your team meets to discuss the themes and how to apply them to your work. You decide as a team to create a concept for a web-based onboarding experience that facilitates transparency into how the bank applies fees to accounts, that addresses how the client allows users to share personal banking experiences and to invite others, and that covers key aspects of onboarding that your participants said were lacking from their account-opening experiences.

You have reached one of the two requirements for saturation: You have collected enough meaningful data to identify key themes and make recommendations. You have an actionable takeaway from your findings: to create an onboarding experience that highlights transparency and personal connections. And it only took you 12 participants to get there. You finish the last three interviews to validate what you’ve heard and to stockpile more data for the next component of saturation.

Saturation Of Data Analysis

You thoroughly analyze the data you have collected to reach saturation of data analysis. This means you’ve done your due diligence in analyzing the data you’ve collected, whether the sample size is 1 or 100. You can analyze qualitative data in many ways. Some of the ways depend on the exact method of data collection you’ve followed.

You will need to code all of your data. You can create codes inductively (based on what the data tell you) or deductively (predetermined codes). You are trying to identify meaningful themes and points made in the data. You saturate data analysis when you have coded all data and identified themes supported by the coded data. This is also where the researcher’s experience comes into play. Experience will help you to identify meaningful codes and themes more quickly and to translate them into actionable recommendations.

Going back to our banking example, you’ve presented your findings and proposed an onboarding experience to your client. The client likes the idea, but also suggests there might be more information to uncover about the lack of transparency. They suggest you find a few more people to interview about this theme specifically.

You ask another researcher to review your data before you agree to interview more people. This researcher finds variation in the transparency-themed quotes that the current codes don’t cover: Some users think banks lack transparency around fees and services. Others mention that banks lack transparency in how client information is stored and used. Initially, you only coded a lack of transparency in fee structures. The additional pair of eyes reviewing your data enables you to reach saturation of analysis. Your designers begin to account for this variation of transparency in the onboarding experience and throughout. They highlight bank privacy and data-security policies.

You have a discussion with your client and suggest not moving forward with additional interviews. You were able to reach saturation of data analysis once you reviewed the data and applied additional codes. You don’t need additional interviews.

Sample Size Formula And Data Saturation Case Study

Let’s run through a case study covering the concepts presented in this article.

Suppose we are working with a client to conceptualize a redesign of their clinical data-management application. Researchers use clinical data-management applications to collect and store data from clinical trials. Clinical trials are studies that test the effectiveness of new medical treatments. The client wants us to identify areas to improve the design of their product and to increase use and reliability. We will conduct interviews up front to inform our design concepts.

Saturation Of Sample Size

We’ll request 12 interview participants based on the formula in this article. Below is how we’ve determined the value of each variable in the formula.

Scope: We are tasked with providing research-informed design concepts for an existing product. This project does not have a large scope. We are not inventing a new way to collect clinical data, but rather are improving an existing tool. The smaller scope justifies a smaller sample size.

S = 1- Characteristics: Our client identifies three specific user types:

- study designers: users charged with building a study in the system.

- data collectors: users who collect data from patients and enter data into the system.

- study managers: users in charge of data collection and reporting for a project.

C= 3 × 3user typesC = 9

Expertise: Let’s say our lead researcher has 10 years of research experience. Our team has experience with the type of project we are completing. We know exactly how much data we need and what to expect from interviewing 12 people.

E = .20

At this point, our formula is ((1 × 3) ÷ 1.2) = 7.5 participants, before factoring in resources. We’ll round up to 8 participants.

Resources: We know the budget and time resources available. We know from past projects that we’ll have enough resources to conduct up to 15 interviews. We could divert more resources to design if we go with fewer than 15 participants. Adding 4 participants to our current number (8) won’t tax our resources and would allow us to speak to 4 of each user type.

R = 4

We recommend 12 research participants to our client, based on the formula for determining the proposed sample size:

Scope (S) - small scope - updating an existing product (S) = 1Characteristics (C) - 3 user types (C) = 9Expertise (E) - 10 years (E)= 1.20Resources (R) - fine for up to 15 total participants (R) = +4- Our formula is

((SxC)/E) + R; - So,

((1x9)/1.2) + 4 = 12 participantsfor this study.

Saturation Of Data Analysis

We’ll set up a spreadsheet to manage the data we collect. Let’s set up the spreadsheet to first examine the data, with participants in rows and the questions in columns (table 1):

| What are some challenges with the system? | Question 2 | Question 3 | Question 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Protocol deviations can get lost or be misleading because they are not always clearly displayed. This would give too much control to the study coordinator role; they would be able to change too much. A tremendous amount of cleaning needs to get done. |

Next, we add a second tab to the spreadsheet and created codes based on what emerged from the data (table 2):

| Code: Issues with study protocol (deviations) | Code: Unreliable data | Code 3 | Code 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | There isn't consistency looking at the same data. It gives too much control to the study coordinator role. They would be able to change too much. | A tremendous amount of cleaning needs to get done. |

Next, we review the data to identify relevant themes (table 3):

| Theme: "trust in the product" | Theme 2 | Theme 3 | Theme 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coded quote and participant | "I'm not sure if we are compliant." – Participant 1 | |||

| Quote and participant | "It's very configurable, but it's configurable to the point that it's unreliable and not predictable." – Participant 2 |

Trust emerges as a theme almost immediately. Nearly every participant mentions a lack of trust in the system. The study designers tell us they don’t trust the lack of structure in creating a study; the clinical data collectors tell us they don’t trust the novice study designers; and the managers tell us they don’t trust the study’s design, the accuracy of the data collectors or the ability of the system to store and upload data with 100% accuracy.

Our design recommendations for the concepts focus on interactions and functionality to increase trust in the product.

Conclusion

Qualitative user researchers must support our reason for choosing a sample size. We may not be academic researchers, but we should strive for standards in how we determine sample sizes. Standards increase the rigor and integrity of our studies. I’ve provided a formula for helping to justify sample sizes.

We must also make sure to achieve data saturation. We do this by suggesting a reasonable sample size, by collecting data using sound questions and good interviewing techniques, and by thoroughly analyzing the data. Clients and colleagues will appreciate the transparency we provide when we show how we’ve determined our sample size and analyzed our data.

I’ve covered a case study demonstrating use of the formula I’ve proposed for determining qualitative research sample sizes. I’ve also discussed how to analyze data in order to reach data saturation.

We must continue moving forward the conversation on determining qualitative sample sizes. Please share other ideas you’ve encountered or used to determine sample sizes. What standards have you given clients or colleagues when asked how you’ve determined a sample size?

Additional Resources

- “Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research” (PDF), Patricia I. Fusch and Lawrence R. Ness, The Qualitative Report

- “Justifying the Adequacy of Samples in Qualitative Interview-Based Studies” (PDF), Julie Barnett et al, University of Bath

- “How Many Interviews?” (PDF), Sarah Elsie Baker and Rosalind Edwards, National Centre for Research Methods

- “What Is an Adequate Sample Size? Operationalizing Data Saturation For Theory-Based Interview Studies” (PDF), Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen

- “How Many Test Users in a Usability Study,” Jakob Nielsen, Nielsen Norman Group

Further Reading

- Data-Driven Design In The Real World

- Considerations When Conducting User Research In Other Countries: A Brazilian Case Study

- How To Run User Tests At A Conference

- Using Social Media For User Research

Register For Free

Register For Free Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial How To Measure UX and Design Impact, 8h video + UX training

How To Measure UX and Design Impact, 8h video + UX training

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why! JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.