An Abridged Cartoon Introduction To WebAssembly

There’s a lot of hype about WebAssembly in JavaScript circles today. People talk about how blazingly fast it is, and how it’s going to revolutionize web development. But most conversations don’t go into the details of why it’s fast. In this article, Lin Clark explains what exactly it is about WebAssembly that makes it fast.

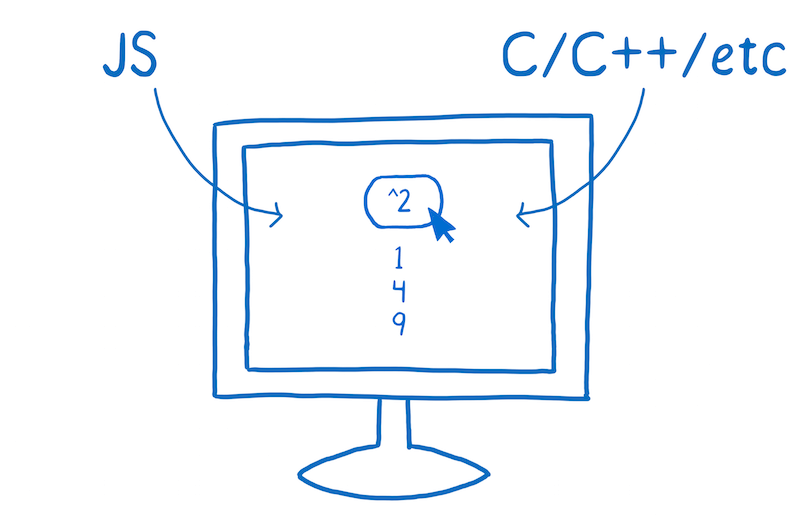

But before we begin, what is it? WebAssembly is a way of taking code written in programming languages other than JavaScript and running that code in the browser.

When you’re talking about WebAssembly, the apples to apples comparison is with JavaScript. Now, I don’t want to imply that it’s an either/or situation — that you’re either using WebAssembly or using JavaScript. In fact, we expect that developers will use WebAssembly and JavaScript hand-in-hand, in the same application. But it is useful to compare the two, so you can understand the potential impact that WebAssembly will have.

A Little Performance History

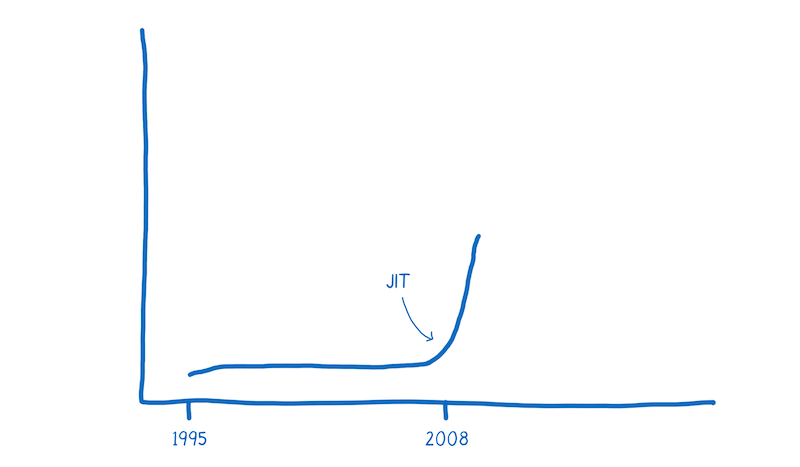

JavaScript was created in 1995. It wasn’t designed to be fast, and for the first decade, it wasn’t fast.

Then the browsers started getting more competitive.

In 2008, a period that people call the performance wars began. Multiple browsers added just-in-time compilers, also called JITs. As JavaScript was running, the JIT could see patterns and make the code run faster based on those patterns.

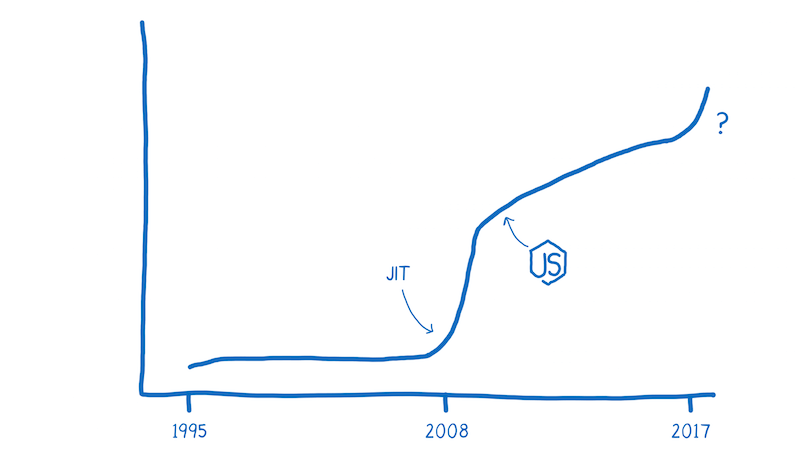

The introduction of these JITs led to an inflection point in the performance of code running in the browser. All of the sudden, JavaScript was running 10x faster.

With this improved performance, JavaScript started being used for things no one ever expected, like applications built with Node.js and Electron.

We may be at another one of those inflection points now with WebAssembly.

Before we can understand the differences in performance between JavaScript and WebAssembly, we need to understand the work that the JS engine does.

How JavaScript Is Run In The Browser

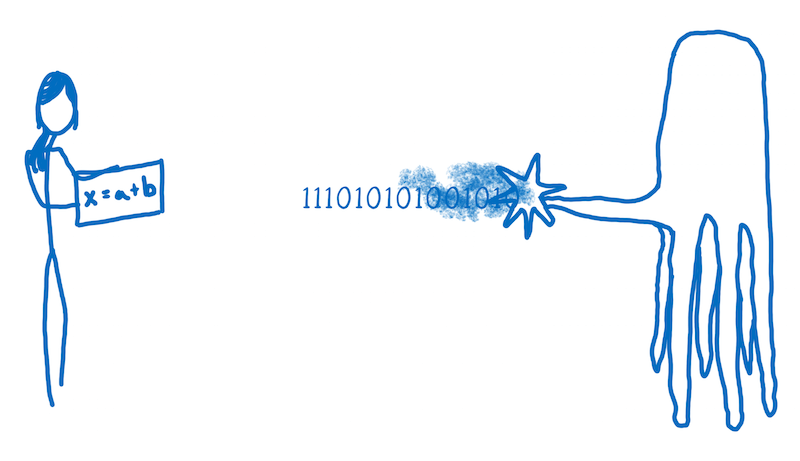

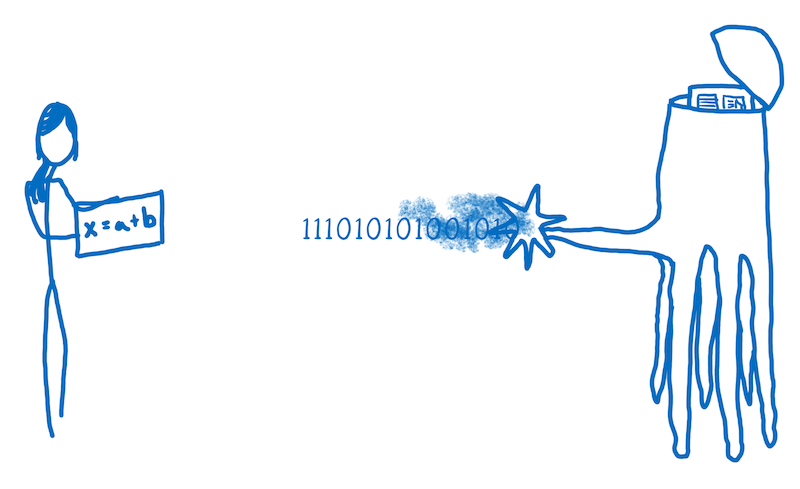

When you as a developer add JavaScript to the page, you have a goal and a problem.

- Goal: you want to tell the computer what to do.

- Problem: you and the computer speak different languages.

You speak a human language, and the computer speaks a machine language. Even if you don’t think about JavaScript or other high-level programming languages as human languages, they really are. They’ve been designed for human cognition, not for machine cognition.

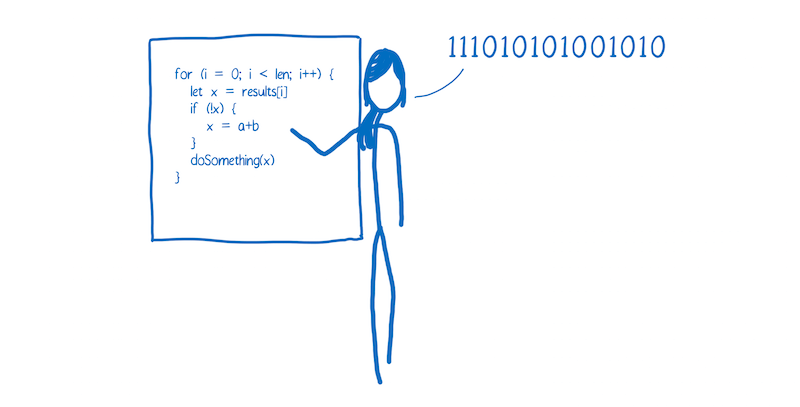

So the job of the JavaScript engine is to take your human language and turn it into something the machine understands.

I think of this like the movie Arrival, where you have humans and aliens who are trying to talk to each other.

In that movie, the humans and aliens can’t just translate from one language to the other, word-for-word. The two groups have different ways of thinking about the world, which is reflected in their language. And that’s true of humans and machines too.

So how does the translation happen?

In programming, there are generally two ways of translating to machine language. You can use an interpreter or a compiler.

With an interpreter, this translation happens pretty much line-by-line, on the fly.

A compiler on the other hand works ahead of time, writing down the translation.

There are pros and cons to each of these ways of handling the translation.

Interpreter Pros And Cons

Interpreters are quick to get code up and running. You don’t have to go through that whole compilation step before you can start running your code. Because of this, an interpreter seems like a natural fit for something like JavaScript. It’s important for a web developer to be able to have that immediate feedback loop.

And that’s part of why browsers used JavaScript interpreters in the beginning.

But the con of using an interpreter comes when you’re running the same code more than once. For example, if you’re in a loop. Then you have to do the same translation over and over and over again.

Compiler Pros And Cons

The compiler has the opposite trade-offs. It takes a little bit more time to start up because it has to go through that compilation step at the beginning. But then code in loops runs faster, because it doesn’t need to repeat the translation for each pass through that loop.

As a way of getting rid of the interpreter’s inefficiency — where the interpreter has to keep retranslating the code every time they go through the loop — browsers started mixing compilers in.

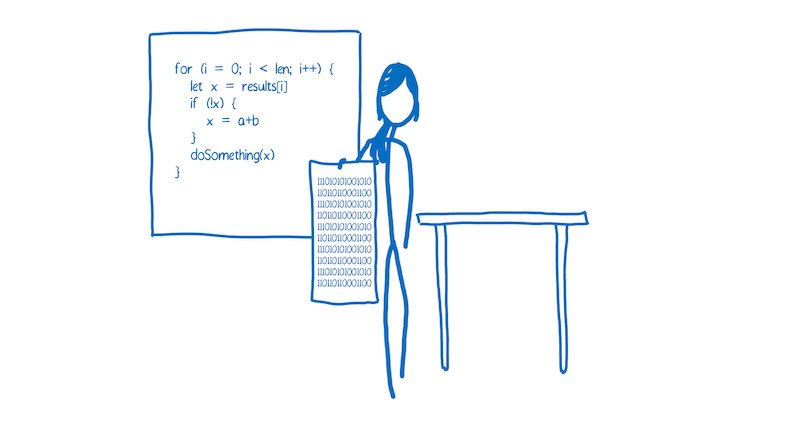

Different browsers do this in slightly different ways, but the basic idea is the same. They added a new part to the JavaScript engine, called a monitor (aka a profiler). That monitor watches the code as it runs, and makes a note of how many times it is run and what types are used.

If the same lines of code are run a few times, that segment of code is called warm. If it’s run a lot, then it’s called hot. Warm code is put through a baseline compiler, which speeds it up a bit. Hot code is put through an optimizing compiler, which speeds it up more.

To learn more, read the full article on just-in-time compiling.

Let’s Compare: Where Time Is Spent When Running JavaScript Vs. WebAssembly

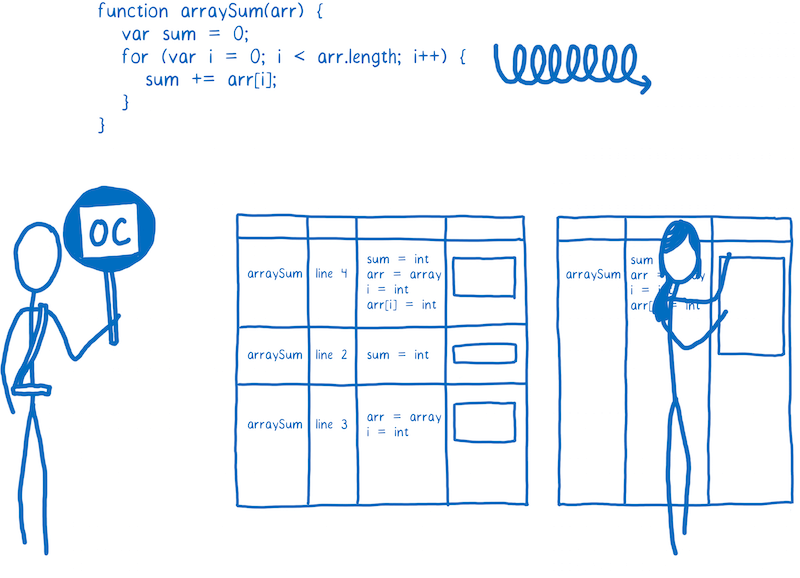

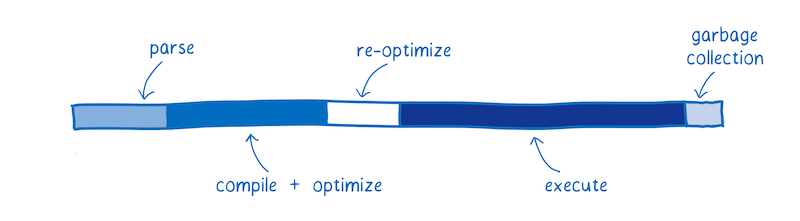

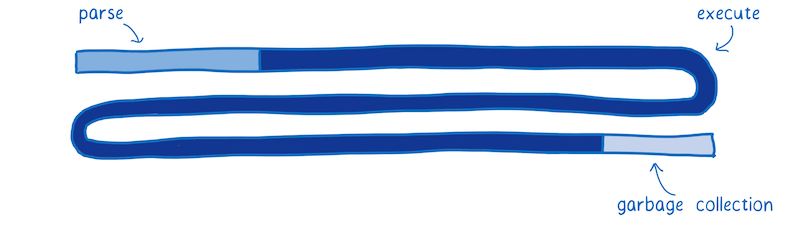

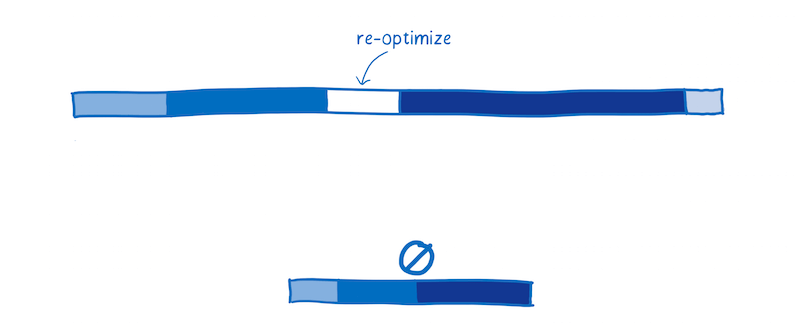

This diagram gives a rough picture of what the start-up performance of an application might look like today, now that JIT compilers are common in browsers.

"This diagram shows where the JS engine spends its time for a hypothetical app. This isn’t showing an average. The time that the JS engine spends doing any one of these tasks depends on the kind of work the JavaScript on the page is doing. But we can use this diagram to build a mental model."

Each bar shows the time spent doing a particular task.

- Parsing — the time it takes to process the source code into something that the interpreter can run.

- Compiling + optimizing — the time that is spent in the baseline compiler and optimizing compiler. Some of the optimizing compiler’s work is not on the main thread, so it is not included here.

- Re-optimizing — the time the JIT spends readjusting when its assumptions have failed, both re-optimizing code and bailing out of optimized code back to the baseline code.

- Execution — the time it takes to run the code.

- Garbage collection — the time spent cleaning up memory.

One important thing to note: these tasks don’t happen in discrete chunks or in a particular sequence. Instead, they will be interleaved. A little bit of parsing will happen, then some execution, then some compiling, then some more parsing, then some more execution, etc.

This performance breakdown is a big improvement from the early days of JavaScript, which would have looked more like this:

In the beginning, when it was just an interpreter running the JavaScript, execution was pretty slow. When JITs were introduced, it drastically sped up execution time.

The tradeoff is the overhead of monitoring and compiling the code. If JavaScript developers kept writing JavaScript in the same way that they did then, the parse and compile times would be tiny. But the improved performance led developers to create larger JavaScript applications.

This means there’s still room for improvement.

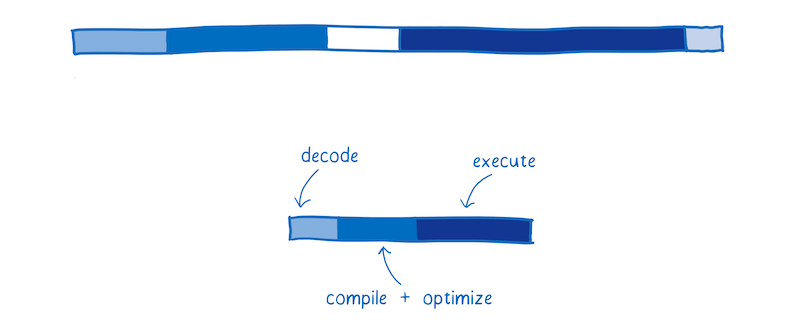

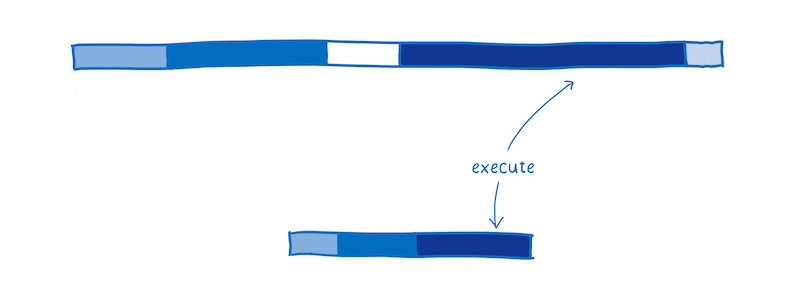

Here’s an approximation of how WebAssembly would compare for a typical web application.

There are slight variations between browsers’ JS engines. I’m basing this on SpiderMonkey.

Fetching

This isn’t shown in the diagram, but one thing that takes up time is simply fetching the file from the server.

It takes less time to download WebAssembly it does the equivalent JavaScript, because it’s more compact. WebAssembly was designed to be compact, and it can be expressed in a binary form.

Even though gzipped JavaScript is pretty small, the equivalent code in WebAssembly is still likely to be smaller.

This means it takes less time to transfer it between the server and the client. This is especially true over slow networks.

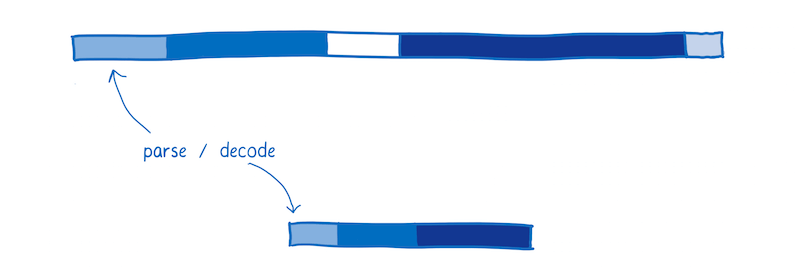

Parsing

Once it reaches the browser, JavaScript source gets parsed into an Abstract Syntax Tree.

Browsers often do this lazily, only parsing what they really need to at first and just creating stubs for functions which haven’t been called yet.

From there, the AST is converted to an intermediate representation (called bytecode) that is specific to that JS engine.

In contrast, WebAssembly doesn’t need to go through this transformation because it is already a bytecode. It just needs to be decoded and validated to make sure there aren’t any errors in it.

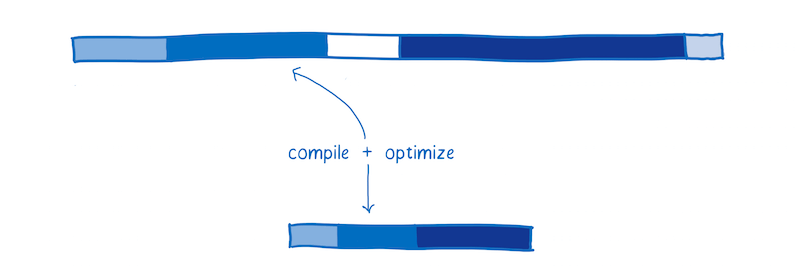

Compiling + Optimizing

As I explained before, JavaScript is compiled during the execution of the code. Because types in JavaScript are dynamic, multiple versions of the same code may need to be compiled for different types. This takes time.

In contrast, WebAssembly starts off much closer to machine code. For example, the types are part of the program. This is faster for a few reasons:

- The compiler doesn’t have to spend time running the code to observe what types are being used before it starts compiling optimized code.

- The compiler doesn’t have to compile different versions of the same code based on those different types it observes.

- More optimizations have already been done ahead of time in LLVM. So less work is needed to compile and optimize it.

Reoptimizing

Sometimes the JIT has to throw out an optimized version of the code and retry it.

This happens when assumptions that the JIT makes based on running code turn out to be incorrect. For example, deoptimization happens when the variables coming into a loop are different than they were in previous iterations, or when a new function is inserted in the prototype chain.

In WebAssembly, things like types are explicit, so the JIT doesn’t need to make assumptions about types based on data it gathers during runtime. This means it doesn’t have to go through reoptimization cycles.

Executing

It is possible to write JavaScript that executes performantly. To do it, you need to know about the optimizations that the JIT makes.

However, most developers don’t know about JIT internals. Even for those developers who do know about JIT internals, it can be hard to hit the sweet spot. Many coding patterns that people use to make their code more readable (such as abstracting common tasks into functions that work across types) get in the way of the compiler when it’s trying to optimize the code.

Because of this, executing code in WebAssembly is generally faster. Many of the optimizations that JITs make to JavaScript just aren’t necessary with WebAssembly.

In addition, WebAssembly was designed as a compiler target. This means it was designed for compilers to generate, and not for human programmers to write.

Since human programmers don’t need to program it directly, WebAssembly can provide a set of instructions that are more ideal for machines. Depending on what kind of work your code is doing, these instructions run anywhere from 10% to 800% faster.

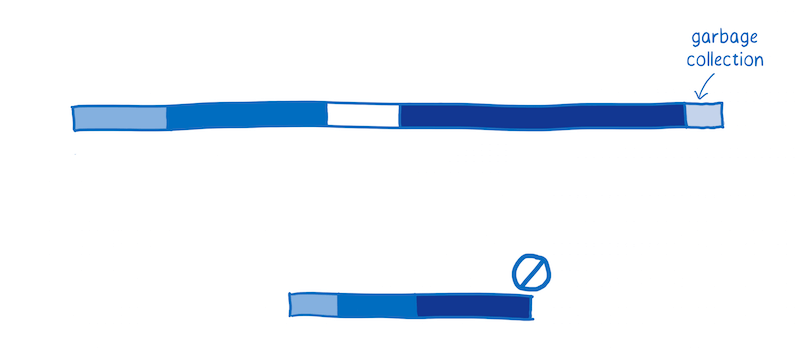

Garbage Collection

In JavaScript, the developer doesn’t have to worry about clearing out old variables from memory when they aren’t needed anymore. Instead, the JS engine does that automatically using something called a garbage collector.

This can be a problem if you want predictable performance, though. You don’t control when the garbage collector does its work, so it may come at an inconvenient time.

For now, WebAssembly does not support garbage collection at all. Memory is managed manually (as it is in languages like C and C++). While this can make programming more difficult for the developer, it does also make performance more consistent.

Taken together, these are all reasons why in many cases, WebAssembly will outperform JavaScript when doing the same task.

There are some cases where WebAssembly doesn’t perform as well as expected, and there are also some changes on the horizon that will make it faster. I have covered these future features in more depth in another article.

How Does WebAssembly Work?

Now that you understand why developers are excited about WebAssembly, let’s look at how it works.

When I was talking about JITs above, I talked about how communicating with the machine is like communicating with an alien.

I want to take a look now at how that alien brain works — how the machine’s brain parses and understands the communication coming in to it.

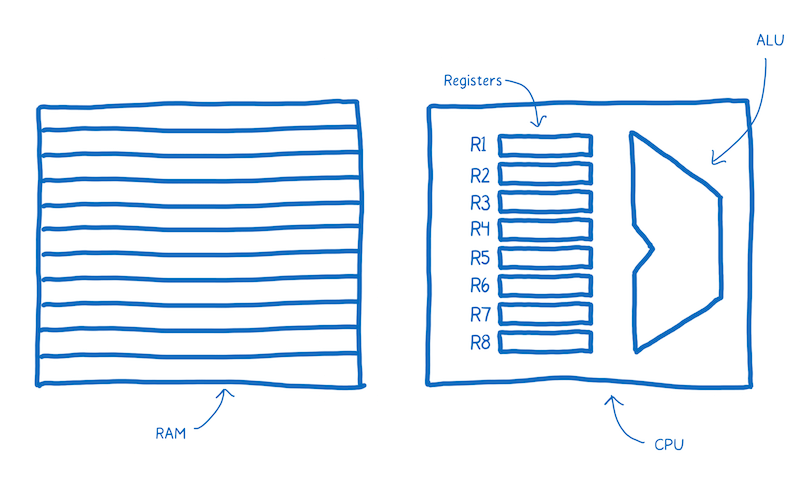

There’s a part of this brain that’s dedicated to the thinking , e.g. arithmetic and logic. There’s also a part of the brain near that which provides short-term memory, and another part that provides longer-term memory.

These different parts have names.

- The part that does the thinking is the Arithmetic-logic Unit (ALU).

- The short term memory is provided by registers.

- The longer term memory is the Random Access Memory (or RAM).

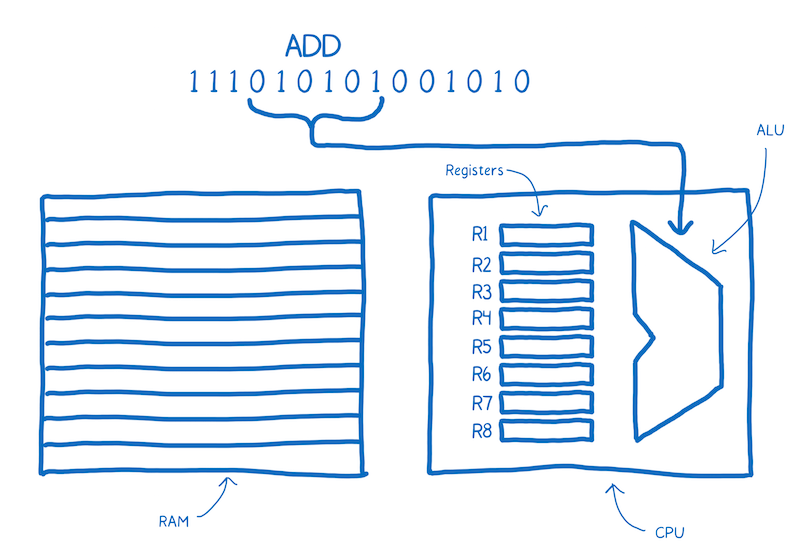

The sentences in machine code are called instructions.

What happens when one of these instructions comes into the brain? It gets split up into different parts that mean different things.

The way that this instruction is split up is specific to the wiring of this brain.

For example, this brain might always take bits 4–10 and send them to the ALU. The ALU will figure out, based on the location of ones and zeros, that it needs to add two things together.

This chunk is called the “opcode”, or operation code, because it tells the ALU what operation to perform.

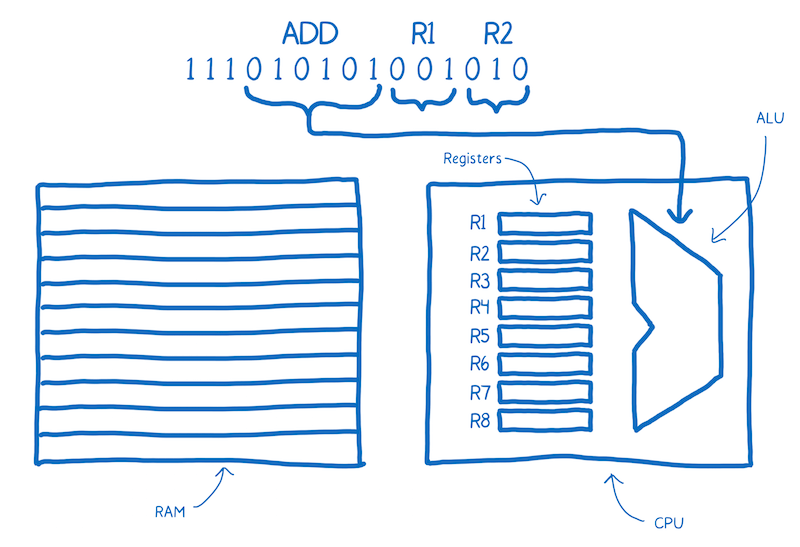

Then this brain would take the next two chunks to determine which two numbers it should add. These would be addresses of the registers.

Note the annotations I’ve added above the machine code here, which make it easier for us to understand what’s going on. This is what assembly is. It’s called symbolic machine code. It’s a way for humans to make sense of the machine code.

You can see here there is a pretty direct relationship between the assembly and the machine code for this machine. When you have a different architecture inside of a machine, it is likely to require its own dialect of assembly.

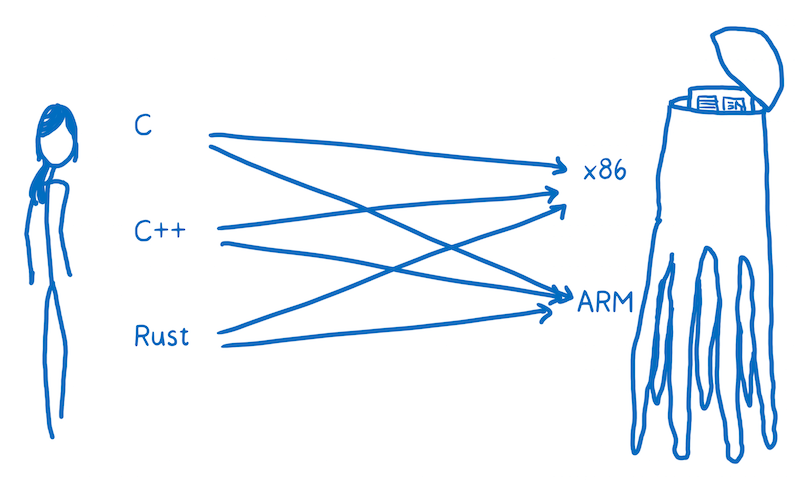

So we don’t just have one target for our translation. Instead, we target many different kinds of machine code. Just as we speak different languages as people, machines speak different languages.

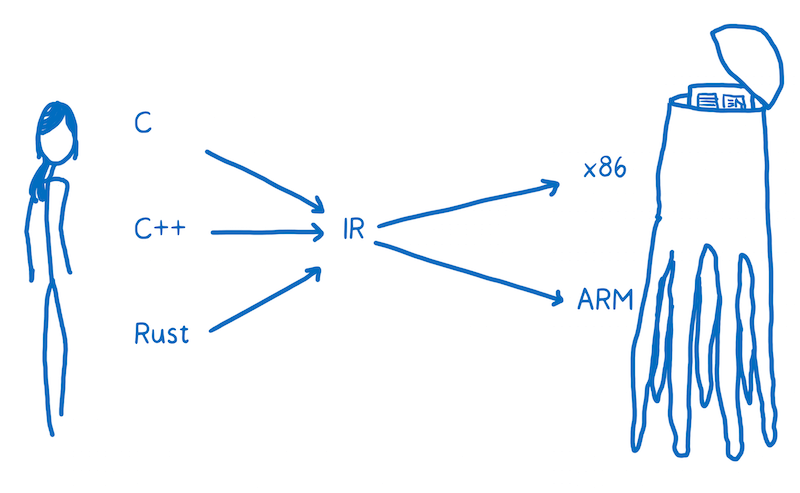

You want to be able to translate any one of these high-level programming languages down to any one of these assembly languages. One way to do this would be to create a whole bunch of different translators that can go from each language to each assembly.

That’s going to be pretty inefficient. To solve this, most compilers put at least one layer in between. The compiler will take this high-level programming language and translate it into something that’s not quite as high level, but also isn’t working at the level of machine code. And that’s called an intermediate representation (IR).

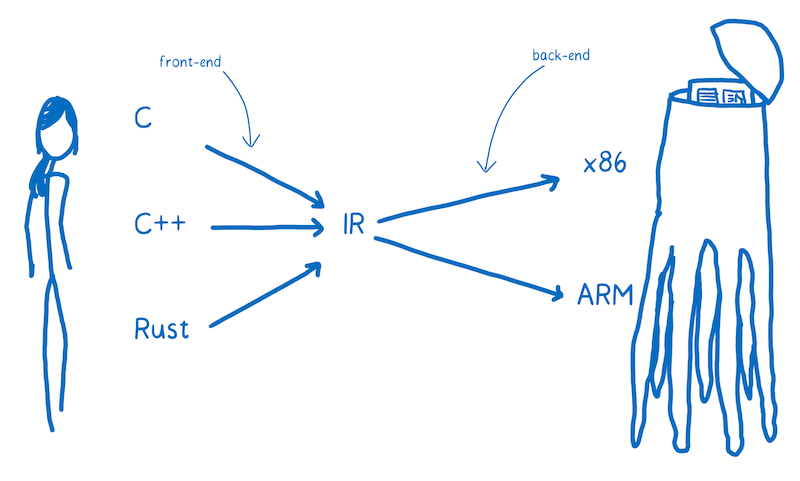

This means the compiler can take any one of these higher-level languages and translate it to the one IR language. From there, another part of the compiler can take that IR and compile it down to something specific to the target architecture.

The compiler’s front-end translates the higher-level programming language to the IR. The compiler’s backend goes from IR to the target architecture’s assembly code.

Where Does WebAssembly Fit?

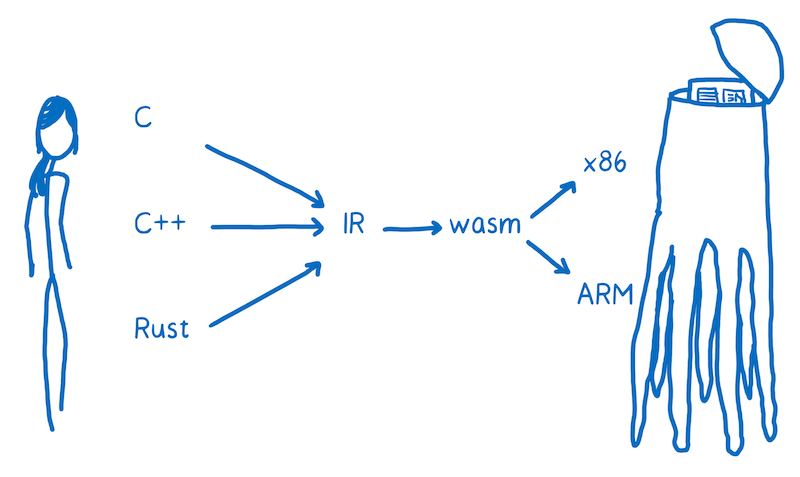

You might think of WebAssembly as just another one of the target assembly languages. That is kind of true, except that each one of those languages (x86, ARM, etc) corresponds to a particular machine architecture.

When you’re delivering code to be executed on the user’s machine across the web, you don’t know what target architecture the code will be running on.

So WebAssembly is a little bit different than other kinds of assembly. It’s a machine language for a conceptual machine, not an actual, physical machine.

Because of this, WebAssembly instructions are sometimes called virtual instructions. They have a much more direct mapping to machine code than JavaScript source code, but they don’t directly correspond to the particular machine code of one specific hardware.

The browser downloads the WebAssembly. Then, it can make the short hop from WebAssembly to that target machine’s assembly code.

To add WebAssembly to your web page, you need to compile it into a .wasm file.

Compiling To .wasm

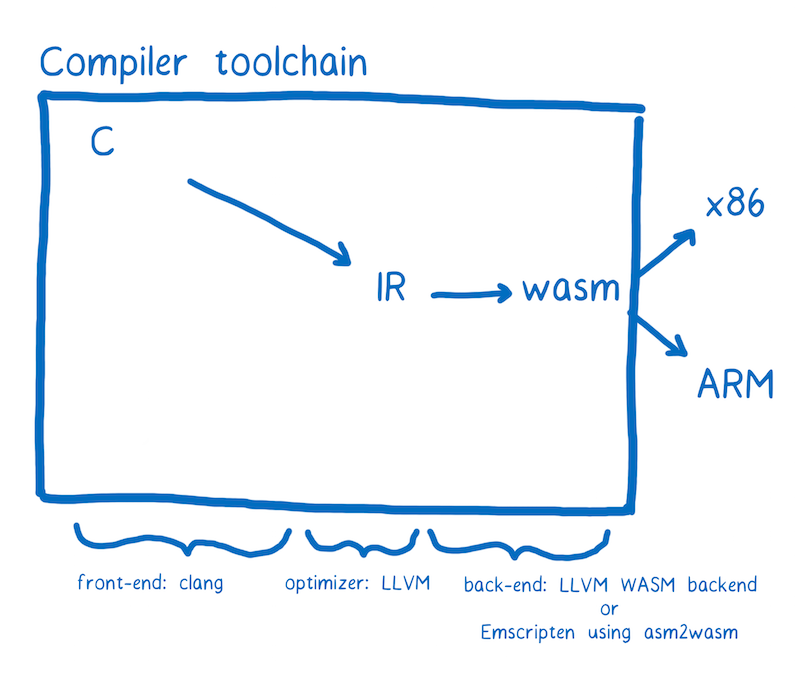

The compiler tool chain that currently has the most support for WebAssembly is called LLVM. There are a number of different front-ends and back-ends that can be plugged into LLVM.

Note: Most WebAssembly module developers will code in languages like C and Rust and then compile to WebAssembly, but there are other ways to create a WebAssembly module. For example, there is an experimental tool that helps you build a WebAssembly module using TypeScript, or you can code in the text representation of WebAssembly directly.

Let’s say that we wanted to go from C to WebAssembly. We could use the clang front-end to go from C to the LLVM intermediate representation. Once it’s in LLVM’s IR, LLVM understands it, so LLVM can perform some optimizations.

To go from LLVM’s IR to WebAssembly, we need a back-end. There is one that’s currently in progress in the LLVM project. That back-end is most of the way there and should be finalized soon. However, it can be tricky to get it working today.

There’s another tool called Emscripten which is a bit easier to use. It also optionally provides helpful libraries, such as a filesystem backed by IndexDB.

Regardless of the toolchain you’ve used, the end result is a file that ends in .wasm. Let’s look at how you can use it in your web page.

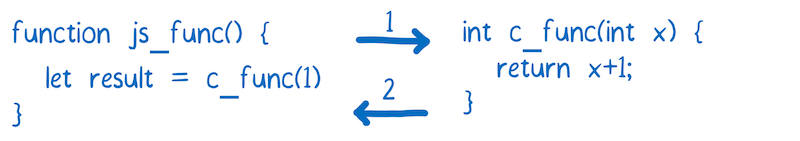

Loading A .wasm Module In JavaScript

The .wasm file is the WebAssembly module, and it can be loaded in JavaScript. As of this moment, the loading process is a little bit complicated.

function fetchAndInstantiate(url, importObject) {

return fetch(url).then(response =>

response.arrayBuffer()

).then(bytes =>

WebAssembly.instantiate(bytes, importObject)

).then(results =>

results.instance

);

}

You can see this in more depth in our docs.

We’re working on making this process easier. We expect to make improvements to the toolchain and integrate with existing module bundlers like webpack or loaders like SystemJS. We believe that loading WebAssembly modules can be as easy as as loading JavaScript ones.

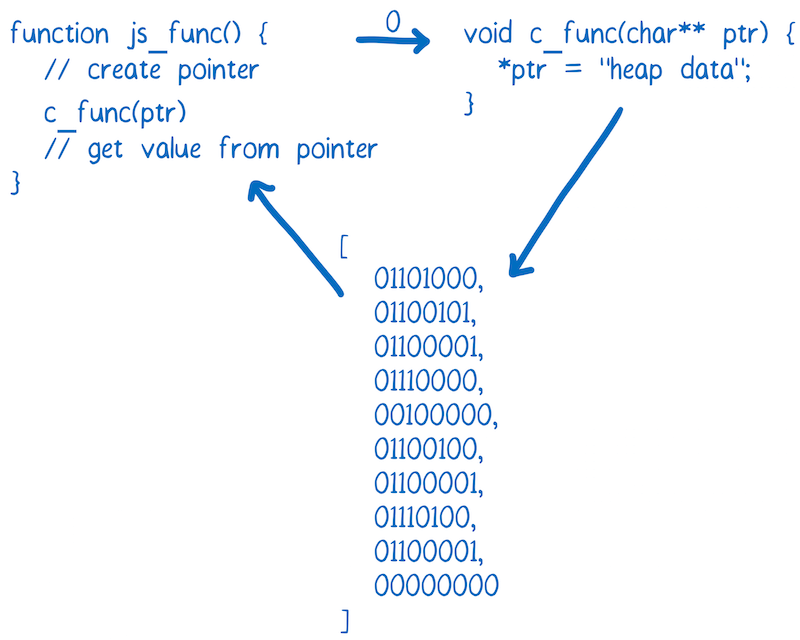

There is a major difference between WebAssembly modules and JS modules, though. Currently, functions in WebAssembly can only use WebAssembly types (integers or floating point numbers) as parameters or return values.

For any data types that are more complex, like strings, you have to use the WebAssembly module’s memory.

If you’ve mostly worked with JavaScript, having direct access to memory is unfamiliar. More performant languages like C, C++, and Rust, tend to have manual memory management. The WebAssembly module’s memory simulates the heap that you would find in those languages.

To do this, it uses something in JavaScript called an ArrayBuffer. The array buffer is an array of bytes. So the indexes of the array serve as memory addresses.

If you want to pass a string between the JavaScript and the WebAssembly, you convert the characters to their character code equivalent. Then you write that into the memory array. Since indexes are integers, an index can be passed in to the WebAssembly function. Thus, the index of the first character of the string can be used as a pointer.

It’s likely that anybody who’s developing a WebAssembly module to be used by web developers is going to create a wrapper around that module. That way, you as a consumer of the module don’t need to know about memory management.

I’ve explained more about working with WebAssembly modules in another article.

What’s The Status Of WebAssembly?

On February 28, the four major browsers announced their consensus that the MVP of WebAssembly is complete. Firefox turned WebAssembly support on-by-default about a week after that, and Chrome followed the next week. It is also available in preview versions of Edge and Safari.

This provides a stable initial version that browsers can start shipping.

This core doesn’t contain all of the features that the community group is planning. Even in the initial release, WebAssembly will be fast. But it should get even faster in the future, through a combination of fixes and new features. I detail some of these features in another article.

Conclusion

With WebAssembly, it is possible to run code on the web faster. There are a number of reasons why WebAssembly code runs faster than its JavaScript equivalent.

- Downloading — it is more compact, so can be faster to download

- Parsing — decoding WebAssembly is faster than parsing JavaScript

- Compiling & optimizing — it takes less time to compile and optimize because more optimizations have been done before the file is pushed to the server, and the code does need to be compiled multiple times for dynamic types

- Re-optimizing — code doesn’t need to be re-optimized because there’s enough information for the compiler to get it right on the first try

- Execution — execution can be faster because WebAssembly instructions are optimized for how the machine thinks

- Garbage Collection — garbage collection is not directly supported by WebAssembly currently, so there is no time spent on GC

What’s currently in browsers is the MVP, which is already fast. It will get even faster over the next few years, as the browsers improve their engines and new features are added to the spec. No one can say for sure what kinds of applications these performance improvements could enable. But if the past is any indication, we can expect to be surprised.

This article has been republished from Hacks.

Further Reading

- Recovering Deleted Files From Your Git Working Tree

- How Marketing Changed OOP In JavaScript

- SolidStart: A Different Breed Of Meta-Framework

- Useful DevTools Tips and Tricks

Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why! Register For Free

Register For Free

How To Measure UX and Design Impact, 8h video + UX training

How To Measure UX and Design Impact, 8h video + UX training