A Guide To The State Of Print Stylesheets In 2018

Today, I’d like to return to a subject that has already been covered in Smashing Magazine in the past — the topic of the print stylesheet. In this case, I am talking about printing pages directly from the browser. It’s an experience that can lead to frustration with enormous images (and even advertising) being printed out. Just sometimes, however, it adds a little bit of delight when a nicely optimized page comes out of the printer using a minimum of ink and paper and ensuring that everything is easy to read.

This article will explore how we can best create that second experience. We will take a look at how we should include print styles in our web pages, and look at the specifications that really come into their own once printing. We’ll find out about the state of browser support, and how to best test our print styles. I’ll then give you some pointers as to what to do when a print stylesheet isn’t enough for your printing needs.

Key Places For Print Support

If you still have not implemented any print styles on your site, there are a few key places where a solid print experience will be helpful to your users. For example, many users will want to print a transaction confirmation page after making a purchase or booking even if you will send details via email.

Any information that your visitor might want to use when away from their computer is also a good candidate for a print stylesheet. The most common thing that I print are recipes. I could load them up on my iPad but it is often more convenient to simply print the recipe to pop onto the fridge door while I cook. Other such examples might be directions or travel information. When traveling abroad and not always having access to data these printouts can be invaluable.

Reference materials of any sort are also often printed. For many people, being able to make notes on paper copies is the way they best learn. Again, it means the information is accessible in an offline format. It is easy for us to wonder why people want to print web pages, however, our job is often to make content accessible — in the best format for our visitors. If that best format is printed to paper, then who are we to argue?

Why Would This Page Be Printed?

A good question to ask when deciding on the content to include or hide in the print stylesheet is, “Why is the user printing this page?” Well, maybe there’s a recipe they’d like to follow while cooking in the kitchen or take along with them when shopping to buy ingredients. Or they’d like to print out a confirmation page after purchasing a ticket as proof of booking. Or perhaps they’d like a receipt or invoice to be printed (or printed to PDF) in order to store it in the accounts either as paper or electronically.

Considering the use of the printed document can help you to produce a print version of your content that is most useful in the context in which the user is in when referring to that print-out.

Workflow

Once we have decided to include print styles in our CSS, we need to add them to our workflow to ensure that when we make changes to the layout we also include those changes in the print version.

Adding Print Styles To A Page

To enable a “print stylesheet” what we are doing is telling the browser what these CSS rules are for when the document is printed. One method of doing this is to link an additional stylesheet by using the <link> element.

<link rel="stylesheet" media="print" href="print.css">

This method does keep your print styles separate from everything else which you might consider to be tidier, however, that has downsides.

The linked stylesheet creates an additional request to the server. In addition, that nice, neat separation of print styles from other styles can have a downside. While you may take care to update the separate styles before going live, the stylesheet may find itself suffering due to being out of sight and therefore out of mind — ultimately becoming useless as features are added to the site but not reflected in the print styles.

The alternate method for including print styles is to use @media in the same way that you includes CSS for certain breakpoints in your responsive design. This method keeps all of the CSS together for a feature. Styles for narrow to wide breakpoints, and styles for print. Alongside Feature Queries with @supports, this encourages a way of development that ensures that all of the CSS for a design feature is kept and maintained together.

@media print {

}Overwriting Screen CSS Or Creating Separate Rules

Much of the time you are likely to find that the CSS you use for the screen display works for print with a few small adjustments. Therefore you only need to write CSS for print, for changes to that basic CSS. You might overwrite a font size, or family, yet leave other elements in the CSS alone.

If you really want to have completely separate styles for print and start with a blank slate then you will need to wrap the rest of your site styles in a Media Query with the screen keyword.

@media screen {

}On that note, if you are using Media Queries for your Responsive Design, then you may have written them for screen.

@media screen and (min-width: 500px) {

}If you want these styles to be used when printing, then you should remove the screen keyword. In practice, however, I often find that if I work “mobile first” the single column mobile layout is a really good starting point for my print layout. By having the media queries that bring in the more complex layouts for screen only, I have far less overwriting of styles to do for print.

Add Your Print Styles To Your Pattern Libraries And Style Guides

To help ensure that your print styles are seen as an integral part of the site design, add them to your style guide or pattern library for the site if you have one. That way there is always a reminder that the print styles exist, and that any new pattern created will need to have an equivalent print version. In this way, you are giving the print styles visibility as a first-class citizen of your design system.

Basics Of CSS For Print

When it comes to creating the CSS for print, there are three things you are likely to find yourself doing. You will want to hide, and not display content which is irrelevant when printed. You may also want to add content to make a print version more useful. You might also want to adjust fonts or other elements of your page to optimize them for print. Let’s take a look at these techniques.

Hiding Content

In CSS the method to hide content and also prevent generation of boxes is to use the display property with a value of none.

.box {

display: none;

}Using display: none will collapse the element and all of its child elements. Therefore, if you have an image gallery marked up as a list, all you would need to do to hide this when printed is to set display: none on the ul.

Things that you might want to hide are images which would be unnecessary when printed, navigation, advertising panels and areas of the page which display links to related content and so on. Referring back to why a user might print the page can help you to decide what to remove.

Inserting Content

There might be some content that makes sense to display when the page is printed. You could have some content set to display: none in a screen stylesheet and show it in your print stylesheet. Additionally, however, you can use CSS to expose content not normally output to the screen. A good example of this would be the URL of a link in the document. In your screen document, a link would normally show the link text which can then be clicked to visit that new page or external website. When printed links cannot be followed, however, it might be useful if the reader could see the URL in case they wished to visit the link at a later time.

We achieve this by using CSS Generated Content. Generated Content gives you a way to insert content into your document via CSS. When printing, this becomes very useful.

You can insert a simple text string into your document. The next example targets the element with a class of wrapper and inserts before it the string, “Please see www.mysite.com for the latest version of this information.”

.wrapper::after {

content: "Please see www.mysite.com for the latest version of this information.";

}You can insert things that already exist in the document however, an example would be the content of the link href. We add Generated Content after each instance of a with an attribute of href and the content we insert is the value of the href attribute - which will be the link.

a[href]:after {

content: " (" attr(href) ")";

}You could use the newer CSS :not selector to exclude internal links if you wished.

a[href^="http"]:not([href*="example.com"]):after {

content: " (" attr(href) ")";

}There are some other useful tips like this in the article, “I Totally Forgot About Print Stylesheets”, written by Manuel Matuzovic.

Advanced Print Styling

If your printed version fits neatly onto one page then you should be able to create a print stylesheet relatively simply by using the techniques of the last section. However, once you have something which prints onto multiple pages (and particularly if it contains elements such as tables or figures), you may find that items break onto new pages in a suboptimal manner. You may also want to control things about the page itself, e.g. changing the margin size.

CSS does have a way to do these things, however, as we will see, browser support is patchy.

Paged Media

The CSS Paged Media Specification opens with the following description of its role.

“This CSS module specifies how pages are generated and laid out to hold fragmented content in a paged presentation. It adds functionality for controlling page margins, page size and orientation, and headers and footers, and extends generated content to enable page numbering and running headers/footers.”

The screen is continuous media; if there is more content, we scroll to see it. There is no concept of it being broken up into individual pages. As soon as we are printing we output to a fixed size page, described in the specification as paged media. The Paged Media specification doesn’t deal with how content is fragmented between pages, we will get to that later. Instead, it looks at the features of the pages themselves.

We need a way to target an individual page, and we do this by using the @page rule. This is used much like a regular selector, in that we target @page and then write CSS to be used by the page. A simple example would be to change the margin on all of the pages created when you print your document.

@page {

margin: 20px;

}You can target specific pages with :left and :right spread pseudo-class selectors. The first page can be targeted with the :first pseudo-class selector and blank pages caused by page breaks can be selected with :blank. For example, to set a top margin only on the first page:

@page :first {

margin-top: 250pt;

}To set a larger margin on the right side of a left-hand page and the left side of a right-hand page:

@page :left {

margin-right: 200pt;

}

@page :right {

margin-left: 200pt;

}The specification defines being able to insert content into the margins created, however, no browser appears to support this feature. I describe this in my article about creating stylesheets for use with print-specific user agents, Designing For Print With CSS.

CSS Fragmentation

Where the Paged Media module deals with the page boxes themselves, the CSS Fragmentation Module details how content breaks between fragmentainers. A fragmentainer (or fragment container) is a container which contains a portion of a fragmented flow. This is a flow which, when it gets to a point where it would overflow, breaks into a new container.

The contexts in which you will encounter fragmentation currently are in paged media, therefore when printing, and also when using Multiple-column layout and your content breaks between column boxes. The Fragmentation specification defines various rules for breaking, CSS properties that give you some control over how content breaks into new fragments, in these contexts. It also defines how content breaks in the CSS Regions specification, although this isn’t something usable cross-browser right now.

And, speaking of browsers, fragmentation is a bit of a mess in terms of support at the moment. The browser compatibility tables for each property on MDN seem to be accurate as to support, however testing use of these properties carefully will be required.

Older Properties From CSS2

In addition to the break-* properties from CSS Fragmentation Level 3, we have page-break-* properties which came from CSS2. In spec terms, these have been superseded by the newer break-* properties, as these are more generic and can be used in the different contexts breaking happens. There isn’t much difference between a page and a multicol break. However, in terms of browser support, there is better browser support for the older properties. This means you may well need to use those at the current time to control breaking. Browsers that implement the newer properties are to alias the older ones rather than drop them.

In the examples that follow, I shall show both the new property and the old one where it exists.

break-before & break-after

These properties deal with breaks between boxes, and accept the following values, with the initial value being auto. The final four values do not apply to paged media, instead being for multicol and regions.

autoavoidavoid-pagepageleftrightrectoversoavoid-columncolumnavoid-regionregion

The older properties of page-break-before and page-break-after accept a smaller range of values.

autoalwaysavoidleftrightinherit

To always cause a page break before an h2 element, you would use the following:

h2 {

break-before: page;

}To avoid a paragraph being detached from the heading immediately preceding it:

h2, h3 {

break-after: avoid-page;

}The older page-break-* property to always cause a page break before an h2:

h2 {

page-break-before: always;

}To avoid a paragraph being detached from the heading immediately preceding it:

h2, h3{

page-break-after: avoid;

}On MDN find information and usage examples for the properties:

break-inside

This property controls breaks inside boxes and accepts the values:

autoavoidavoid-pageavoid-columnavoid-region

As with the previous two properties, there is an aliased page-break-inside from CSS2, which accepts the values:

autoavoidinherit

For example, perhaps you have a figure or a table and you don’t want a half of it to end up on one page and the other half on another page.

figure {

break-inside: avoid;

}And when using the older property:

figure {

page-break-inside: avoid;

}On MDN:

Orphans And Widows

The Fragmentation specification also defines the properties orphans and widows. The orphans property defines how many lines can be left at the bottom of the first page when content such as a paragraph is broken between two pages. The widows property defines how many lines may be left at the top of the second page.

Therefore, in order to prevent ending up with a single line at the end of a page and a single line at the top the next page, you can use the following:

p {

orphans: 2;

widows: 2;

}The widows and orphans properties are well supported (the missing browser implementation being Firefox).

On MDN:

box-decoration-break

The final property defined in the Fragmentation module is box-decoration-break. This property deals with whether borders, margins, and padding break or wrap the content. The values it accepts are:

sliceclone

For example, if my content area has a 10-pixel grey border and I print the content, then the default way that this will print is that the border will continue onto each page, however, it will only wrap at the end of the content. So we get a break before going to the next page and continuing.

If I use box-decoration-break: clone, the border and any padding and margin will complete on each page, thus giving each page a grey border.

Currently, this only works for Paged Media in Firefox, and you can find out more about box-decoration-break on MDN.

Browser Support

As already mentioned, browser support is patchy for Paged Media and Fragmentation. Where Fragmentation is concerned, an additional issue is that breaking has to be specified and implemented for each layout method. If you were hoping to use Flexbox or CSS Grid in print stylesheets, you will probably be disappointed. You can check out the Chrome bugs for Flexbox and for Grid.

The best suggestion I can give right now is to keep your print stylesheets reasonably simple. Add fragmentation properties — including both the old page-break-* properties as well as the new properties. However, accept that these may well not work in all browsers. And, if you find lack of browser support frustrating, raise these issues with browsers or vote for already raised issues. Fragmentation, in particular, should be treated as a suggestion rather than a command, even where it is supported. It would be possible to be so specific about where and when you want things to break that it is almost impossible to lay out the pages. You should assume that sometimes you may get suboptimal breaking.

Testing Print Stylesheets

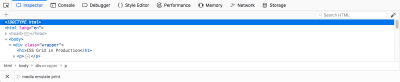

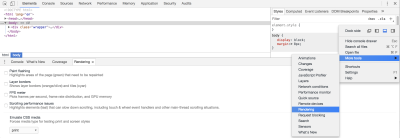

Testing print stylesheets can be something of a bore, typically requiring using print preview or printing to a PDF repeatedly. However, browser DevTools have made this a little easier for us. Both Chrome and Firefox have a way to view the print styles only.

Firefox

Open the Developer Toolbar then type media emulate print at the prompt.

Chrome

Open DevTools, click on the three dots icon and then select “More Tools” and “Rendering”. You can then select print under Emulate CSS Media.

This will only be helpful in testing changes to the CSS layout, hidden or generated content. It can’t help you with fragmentation — you will need to print or print to PDF for that. However, it will save you a few round trips to the printer and can help you check as you develop new parts of the site that you are still hiding and showing the correct things.

What To Do When A Print Stylesheet Isn’t Enough

In an ideal world, browsers would have implemented more of the Paged Media specification when printing direct from the browser, and fragmentation would be more thoroughly implemented in a consistent way. It is certainly worth raising the bugs that you find when printing from the browser with the browsers concerned. If we don’t request these things are fixed, they will remain low priority to be fixed.

If you do need to have a high level of print support and want to use CSS, then currently you would need to use a print-specific User Agent, such as Prince. I detail how you can use CSS to format books when outputting to Prince in my article “Designing For Print With CSS.”

Prince is also available to install on your server in order to generate nicely printed documents using CSS on the web, however, it comes at a high price. An alternative is a server like DocRaptor who offer an API on top of the Prince rendering engine.

There are open-source HTML- and CSS-to-PDF generators such as wkhtmltopdf, but most use browser rendering engines to create the print output and therefore have the same limitations as browsers when it comes to implementing the Paged Media and Fragmentation specifications. An exception is WeasyPrint which seems to have its own implementation and supports slightly different features, although is not in any way as full-featured as something like Prince.

You will find more information about user agents for print on the print-css.rocks site.

Other Resources

Due to the fact that printing from CSS has really moved on very little in the past few years, many older resources on Smashing Magazine and elsewhere are still valid. Some additional tips and tricks can be found in the following resources. If you have discovered a useful print workflow or technical tip, then add it to the comments below.

- “I Totally Forgot About Print Stylesheets,” Manuel Matuzovic, UX Collective

- “Print Stylesheet Approaches: Blacklist vs Whitelist,” Chris Coyier, CSS-Tricks

- “The Perfect Print Stylesheet,” Andreas Hecht, Noupe

- “How To Set Up A Print Stylesheet,” Christian Krammer, Smashing Magazine

- “5 Powerful Tips And Tricks For Print Style Sheets,” Dudley Storey, Smashing Magazine

Further Reading

- CSS Blurry Shimmer Effect

- Building Web Layouts For Dual-Screen And Foldable Devices

- How To Draw Radar Charts In Web

- Useful DevTools Tips and Tricks

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!

Devs love Storyblok - Learn why!

Register For Free

Register For Free JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding.

JavaScript Form Builder — Create JSON-driven forms without coding. Get a Free Trial

Get a Free Trial