How To Sound Like A Cloud Expert

Your code is written and the design looks great. The new project is almost ready to go when the client asks, “Should this run in the cloud?”

You break out in a cold sweat. The question is massive. Regions and zones, high availability, load balancing — the cloud has its own language.

Don’t worry; you’ve got this. This article will teach you how to make smart decisions about the cloud, and answer your client’s cloud questions.

Four Big Questions

Before you and your client can know what kind of cloud you want, you need to discuss four questions:

- How complex is the software you need to run?

- How much does it need to scale?

- How important is it that it never goes down?

- How fast does it need to run for users around the world?

This article gives you the background and information you need to answer these questions and sound like a cloud expert.

Let’s begin.

- What Is A Cloud?

- Why Your Client Cares About The Cloud

- How Is A Cloud Different From A Hosting Service?

- Why Virtual Machines Matter So Much

- Let’s Talk A Little About Networking

- The Different Types Of Clouds

- The Basic Pieces Of A Cloud

- Questions Your Clients Are Likely To Ask

What Is A Cloud?

When we talk about cloud computing, we really mean the ability to rent a piece of a computer from someone else. That’s all there is to it.

Companies like Amazon and Google have a lot of computers and they’re willing to rent parts of them to you. Renting computers from them is cost-effective because you don’t have to build your own data centers or hire your own staff of experts to run them.

When you rent a part of a computer, you need it to look like a whole computer so you can run any software you want. That’s why providers give you a virtual machine (VM) — software that makes it look like you’re running on your own separate computer.

Why Your Client Cares About The Cloud

Before you learn more about the cloud, it’s important to understand why your client cares. Let’s not dismiss the allure of buzzwords; the cloud is really trendy right now. Your client may just be asking because all the cool kids are doing it, but there are reasons the cool kids are doing it.

Let’s start with the basics. Hosting your own data center would be a pain in the rear. You’d have to worry about power consumption, keeping your hardware up to date, hiring a team of experts to run it, and a thousand other problems that have nothing to do with your business. What would happen if the power went out, there was a flood, or the roof caved in? These are all reasons not to host your website on a server running in your living room.

Not only can you pass on all the headaches to someone else, but having them run the data center gives you three big advantages:

- Clouds are global.

They exist in data centers around the world, including one near your client. That means speed. You don’t want customers in China waiting for data to load from the United States. When I go to Google.com, I get a different data center in Boston than I would in Chicago or L.A., and that’s just in the U.S. That’s a large part of what makes Google’s speed possible. - Clouds grow and shrink.

If I buy a server, I have one server; even if my app doesn’t need the whole computer, I still need to pay for that server. When my app gets really popular, I need to buy more servers fast. The cloud doesn’t work like that. Renting shares of servers means I can change how much I’m renting: I can scale up the order when I’m busy, and scale it down when I don’t need as much. - Clouds never go down.

Never say never…but almost never. Cloud providers talk about “five nines” — that means being up 99.999% of the time (with just 5.26 minutes of downtime a year). You can make that even smaller with services like load balancing and failover.

Those are all reasons clouds can be cool, but you can get some of them from a simple hosting service. If your client is asking about the cloud, you need to know the difference.

How Is A Cloud Different From A Hosting Service?

I have a personal website on a hosting service named Media Temple. My site runs WordPress, so it needs a few things:

- A directory to put my files in

- An HTTP server

- A database

- PHP

My directory runs on Linux, my HTTP server is Apache, my database is MySQL, and it all runs on PHP; that’s why they call it a LAMP stack (Linux-Apache-MySQL-PHP). That may sound like a lot of pieces, but they’re limited. For example, I can’t install new software. If I want to run my database on PostgreSQL, I’m out of luck. I can’t run other languages like Python or Go; I can’t write my own separate programs. I only get a very limited, pre-configured set of things I’m allowed to do.

My website also only runs on one server in one place. Where is that server? I have no idea. I think it’s somewhere in the United States, but other than that I don’t know, and I don’t really care. The hosting provider gives me a single server, I type in a URL, and my site comes up (most of the time).

Hosting providers keep it simple. Some of them host other stacks and some allow a little more configuration, but it’s always a set package.

The fundamental difference between a hosting service and a cloud is the virtual machine. A hosting service just gives me part of an existing operating system. A virtual machine gives me an entire operating system all to myself.

Why Virtual Machines Matter So Much

A virtual machine acts just like a real machine. It can run Linux or Windows and it can do anything a normal computer can do. Apple doesn’t allow you to run OS X on a virtual machine (although a few people have made it work, building a “Hackintosh”).

When you have a virtual machine you have total control. You can run anything you want there — databases, email servers, encryption, even searches for extraterrestrials. The virtual machine allows you to do anything you want.

Having an entire operating system all to yourself is really powerful, but before you can do anything useful you need to access the VM.

Let’s Talk A Little About Networking

Virtual machines are useless if you can’t get to them. You need networking, although networking can get a little complex.

But these basics will give you what you need to get started. Let’s start with an example you’ll be familiar with. It’s probably running in your house right now.

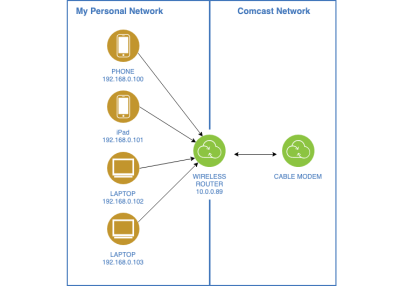

I have Comcast at home. Comcast gives me a cable modem with an IP address like 10.0.0.89. While it only gives me one IP, I have two laptops, an iPad, and a phone; my wife and daughter have even more devices. To make that work, I have a wireless router that connects to my cable modem. My wireless router gives every device I have an IP address like 192.168.0.100, 192.168.0.101, and so on, but those addresses are private to my network.

The technical term for those private addresses is non-routable. There are a few addresses that are set up for private use; most start with 10. or 192.168, as a sign to Internet routers that these addresses aren’t allowed out in the wild. I’m using these special addresses because they’re reusable.

Every IP address must be unique in a given network; otherwise, the router wouldn’t know which computer I wanted to connect to. There are 4,294,967,296 possible IP addresses. Although network designers thought that was a lot when all of this started in the 1970s, we’re now running out. There are some other protocols, like IPv6, that may solve this problem in the future, but today we solve this problem with Network Address Translation (NAT). Let me show you how it works.

The devices in my house have addresses that are unique in my house, but not in the entire world. When I want to get out to the Internet, I need the wireless router to translate them for me. Every time I click a link, my laptop talks to my wireless router to make the request for me; in turn the wireless router talks to the world on my behalf, but using its own address. Then my cable modem does the same thing when it talks to Comcast, and Comcast does the same thing again on a much larger scale when it sends my request out to the general Internet. Each router is translating the IP address from the one before it. All of this means that many computers can reuse an IP address like 192.168.0.101, and it all works out without conflicts.

So what’s my real IP address on the real Internet? Right now my real IP address is 66.30.118.150 and my private IP address is 192.168.0.103.

Where did the address 66.30.118.150 come from? It’s an IP address that Comcast owns. It makes it clear that I’m in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. I don’t need the details; all I need to know is that it’s a real public address that Comcast manages for me. Comcast probably uses the same address for hundreds or thousands of other people.

All of this address translation does something else very important. It gives me a single point of access that controls everything that goes into my home network. Nobody outside can access 192.168.0.103; to them, it’s a different address. I get a lot of security by controlling what traffic can come in and out. My wireless router is a pinch point where I can control what happens.

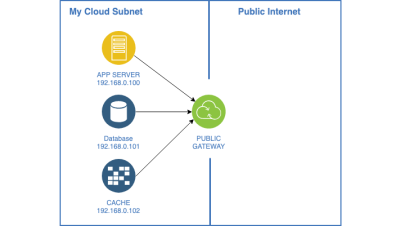

Most clouds work just like my home network. The computers are virtual, networks are called subnets, and the wireless router is called a gateway, but it’s all the same thing. They have virtual machines with private addresses and gateways that translate them to public addresses. They also have a space of addresses that they can use just like my wireless router at home. Like this:

It might sound complicated, but it’s not too hard. A cloud is a way for me to rent computers from someone else and set them up to look like my home network.

The most important things to remember are:

- Private IPs are only available on your private network;

- Public IPs are available on the Internet;

- NAT allows private IPs to look like public IPs.

That’s not everything that happens with cloud networking, but it’s more than enough to get up and running and access your cloud. Now you need to decide what kind of cloud you want.

The Different Types Of Clouds

Cloud is an amorphous term — people use it to mean a lot of different things. There are really three different categories of clouds.

Infrastructure Clouds

The virtual machine and network are the building blocks for an infrastructure cloud, also known as Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). They provide the virtualized infrastructure, which you have full control over. You decide on the operating system and everything else that runs on top of it.

You get flexibility and control, but you’re responsible for managing and supporting everything you install.

Infrastructure clouds are either static or elastic. A static cloud works like my home network: I have a set of virtual machines running whatever I need them to. They live on a private network, with a public gateway that grants them access to the Internet. Static clouds are great for processing data, having some extra computing power, or hosting a more complex site than a hosting provider can handle. You can also replicate your static cloud to other data centers around the world.

Elastic clouds work like static clouds, but they’re dynamic. Instead of a fixed set of virtual servers, you have a set that can grow or shrink depending on your needs. Your cloud expands when you have high demand on your site or service, and shrinks back to normal size when you don’t. All the expanding and shrinking saves you money. You give back the computing power you don’t need when you don’t need it.

Netflix uses IaaS. Amazon Web Services provides the infrastructure, and Netflix implements its entire system on top; it wrote its own software to provide highly customized support for streaming high-definition content. The Weather Company is another example — it runs on top of the IBM Cloud.

Platform Clouds

A platform cloud, also known as Platform as a Service (PaaS), is a specialized cloud that provides software building blocks for your application while the cloud provider manages the infrastructure and software stack for you.

For instance, if you needed a web application, PaaS could provide you with vanilla WordPress or Drupal for you to use. If you needed a database, you could pick MySQL or PostgreSQL. If you need development tools, you might choose from Node, Java, or PHP. You don’t need to worry what operating system is running, or whether a MySQL security patch needs to be applied — the cloud provider takes care of that for you.

Heroku is a PaaS cloud. It provides the software underneath, and you just write what you want on top of that. It gives you some flexibility, but does a lot more management than an IaaS cloud.

Software Clouds

A software cloud, also known as Software as a Service (SaaS), is a very specialized type of cloud that provides you with a well-defined online service. Hosting providers are a special type of SaaS cloud under the covers; they work in a very limited way.

Wix is another example of SaaS. It provides you a complete web application hosting service with a great editor, support for user login and payment, and a wide variety of templates to choose from. Wix focuses on just one job. It’s very limited in functionality, but also easier to use.

The Basic Pieces Of A Cloud

We’ve talked about the different types of clouds and why you need them. Before you can really sound like a cloud expert, you need to know the different components that make up a cloud.

Virtual Machines

A virtual machine is a software that runs like hardware, acting like a real machine without ever needing a separate server anywhere. You can do whatever you want with the VM, and it will pass the duck test — it walks and quacks like a real server. Your software will never know the difference.

This flexibility has a price. You’re responsible for maintaining your virtual machine. The cloud provider will make sure the hardware is in top condition, but you’ll have to select your operating system and everything else that runs on top of it — security patches, software updates, configuration. It’s all on you.

And if you’re not on an elastic cloud, you’d better remember to release any virtual machines you don’t need anymore. The provider will charge you whether the VM is doing work or not.

Subnets

We covered cloud networking already. Subnets are networks that run in the cloud.

Private IPs And Public IPs

The cloud network will assign a non-routable IP address to virtual machines in the subnet. Those are known as private IPs because they’re private to my network. When a virtual machine sends requests to the internet, the public gateway will translate those requests. That’s called egress traffic by the cloud providers.

Just as I can’t access my home printer from a coffee shop, in the cloud I need a public IP to access a virtual machine.

Public IPs can be assigned to virtual machines to allow ingress traffic (traffic coming from the Internet routed to virtual machines). That’s important because cloud providers will charge you differently for ingress and egress traffic.

SSH Keys

An SSH key is a piece of private information that allows you to access your cloud. It’s made up of two files. There’s a public key that looks like this:

ssh-rsa

AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQC5b8xmtjUd1taP4svy9FM/WZc/n5gkqKVkhIsqW27hw2WuhfTVNLA6IBBOs9+br+HlqGYwgYB3DSh0Zm/3Bok1uQhinH77FmKsrPGDpvtJv16weIvGiTMVp+Mct8DVKl48KZxvQKa0Hp6MxEc7cQ9WPvzWn9BPLHERSkSNwXSUobqpFBgIPy9UBWr5DsI2Li5HeMgMgTcbuVVdO/8I/rhKoIyTqkhY4CZcyssmWhMvPmk6+9IcOr0O4SyW9TL+CZgDH1mW2dUypT+1j6HgFjr9H8NfJ4EKnWnFkQXo8HZ4oh6lSTaIfDQfnbrjVUO14N7FW9ZgXbL9cJVx5FLw3ny9 you@them.com

And there’s a private key that looks like this:

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

MIIEogIBAAKCAQEAuW/MZrY1HdbWj+LL8vRTP1mXP5+YJKilZISLKltu4cNlroX0

1TSwOiAQTrPfm6/h5ahmMIGAdw0odGZv9waJNbkIYpx++xZirKzxg6b7Sb9esHiL

xokzFafjHLfA1SpePCmcb0CmtB6ejMRHO3EPVj781p/QTyxxEUpEjcF0lKG6qRQY

CD8vVAVq+Q7CNi4uR3jIDIE3G7lVXTv/CP64SqCMk6pIWOAmXMrLJloTLz5pOvvS

HDq9DuEslvUy/gmYAx9ZltnVMqU/tY+h4BY6/R/DXyeBCp1pxZEF6PB2eKIepUk2

iHw0H52641VDteDexVvWYF2y/XCVceRS8N58vQIDAQABAoIBAHU7UKW+m2X55Dui

zf0SqW5rXUtDwhOq6qTZhoGIvFjOBwKGfXosjRyyGJ0o6jyqvM1L4Q7ZUDXzg5fT

CwXIhAYKrFprRXvHcypnS2hHsKW27k3yZ6tkIX+XW+VT5fzdhCXUyKks3jcRBHtJ

ux7BI0kLGR02e6MSHYkowp47p1Auukx1saRkFTwvy+znABgqVETvtHBxAiElXndL

JfQntaQacgWWDjl2qUj+06IB/Qzd9/Mo1Vtdb8SUZxv/Qc2raSi3LL0N4aSJGLGU

pq395ggv9NdhUQf+DN9uGaOC4hYeGdO8gm27yysZ4rTT5iln5wOaCAcMTMrGL4+k

GoU/nKECgYEA7AP/Mh9sUi9AX/17a3A/zxNAO1ZrvM+Caj/X/t/pt3HEOhqLz7o5

z3g8/Z+H0CJLZNiP9XbMak2wvOiqRj0y+FihX/ESll6XgIEPTBUcFSirWMe4f9og

FltrnelUjHG9MTDW0P4jmmp1E5V8RgnCCv2VjN40ulP5zHPXXdU2FP8CgYEAySNs

/qlFL7DTB/A851y6cUzQC5kiKlr/T8aUtOHeBo626jlnHDy/VY9vIJ0ttsYyHCdM

OSdqZh5wRwvshr94tpOBQNnDTI4Xv7t2couHl7q2xTOYeWViwGyZaatNYlWWFh/u

YSCTd2jn6cvBZOZP3BAiWoF9nzLcsjfpNLdzAkMCgYAx8TaTOKsHSRBqP41aUspt

2zkAVW0+6vpB2Xivalpegyhu0yc6scGB8YOWd6eZl2g00s7DtnvTEtWPY/yEGHcs

rjSXxL+WKjYM70J5aw4iPBTmGH0mMNYRZQ8Ev1cw0PCj9B3A48ZM6rITjtJZT79L

7BU1Vd/6fcKiTPEJ3hAvqQKBgBKOQBnmR8m0iGNtGFFHzrNxIKhRQkOiDXewnDtr

su3r8Jf/H7INMKGWD+x0U6lO84SBY5jKOBifqkADq5hqxZoiVYREEq5XVX2Mr8q1

cJbg1MewkNpyLgAOhMCo2wS9XJFB9N3lAXW8qdh5waerT6a/nku3Mn2jVZTjb5I7

clK9AoGAZLuvLAJpFOf/mweajULV+oFMGzIArvbk1c+cGySeI5uZwfQ9lv2MOb0N

DuFTXZt6QpKV9Nix/8KgBIP2Vac6gSAeF6kIXk2+nV6gXm5tojYrf6gG1jY8ceRD

IFSeGlnBhYVrFcQ79fYwJtSQgGde4PtNF1yq9ipluAyLuy1cLUc=

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

You use these two files together instead of a password.

SSH public-key authentication is a robust way to log in to a remote system, more secure than the standard username and password. (SSH stands for “secure shell.”) You’ve probably seen SSH keys before in the form of your Github key.

SSH keys rely on public-key cryptography and challenge-response authentication to prevent brute-force attacks and other threats.

These keys ensure that only you have access to your virtual machines, and they work great with scripts and other automated tasks.

Data Centers

A data center is a big building full of computers. Cloud providers rent parts of them to you.

The computers are powerful servers that can each host many virtual machines at the same time. These servers consume a lot of power and generate a lot of heat, and they need to be physically close together so the networking is fast. So a data center is the facility in which a cloud provider houses all the physical hardware that runs a piece of its cloud. The data center requires proper cooling, redundant power supply, massive network bandwidth, controlled access and skilled staff to keep all the machines running.

A data center can handle a lot of load, but it’s in just one place. A global cloud provider needs to spread data centers across the world to ensure that clients everywhere will have acceptable network-access latency to their servers.

Regions And Zones

A cloud provider needs to organize its data centers to ensure it can keep fulfilling requests during power outages, floods, hurricanes and other disasters. Providers call this Quality of Service, and it’s all part of making sure the cloud never goes down.

A region is a geographic area with a specific round-trip network latency (from where to where?). Regions have names like Dallas, Tokyo, or Frankfurt. You’re guaranteed to get the network latency you’re paying for inside that area.

A region is made up of one or more zones. Zones are an isolated data center in a region with independent electrical, mechanical and network infrastructure designed to guarantee no shared single point of failure between other zones. That enables you to build highly available fault tolerant applications by deploying to multiple zones in a region. The region can keep going if a zone crashes, but it’s really bad when all the zones go down.

A data center hosts a zone. Multiple data centers are clustered together to create a multi-zone region. Zones have names like us-south-1, us-south-2, and us-south-3. A small region can be served by a single robust data center, while a populous region might require multiple data centers to cope with the network and computing demand.

Disaster Recovery, High Availability, And Fault Tolerance

These concepts make even the most accomplished IT architects sweat. They stay awake at night wondering how they’ll make sure the cloud never goes down.

But you’ve got this! The cloud (almost) never goes down, and it’s easy to make sure you’re covered if it does. Let’s review these concepts one by one:

Disaster recovery (DR) is a set of policies and procedures detailing what to do during and after a major incident. Design your system so that it fails gracefully (meaning that your users will understand that something is wrong but you’ve got it covered), and after an incident, you know how to bring it back as quickly as possible. You need DR when a whole region goes down, your service is under cyber attack, or it’s vulnerable and you need to take it down.

High availability (HA) is but a goal — the “five nines” we talked about earlier. You want your application to be resilient to failure. This is nearly impossible if you run a server in your living room, but it’s doable with the cloud. You achieve the goal of high availability by relying on the cloud’s fault-tolerant infrastructure — everything’s taken care of for you.

A fault-tolerant infrastructure is a design that makes sure a backup takes over if something goes down. The cloud is a fault-tolerant system. If a zone within a region fails, the other zones will ensure continuity of service. You need to take advantage of that fault tolerance by using components like load balancers.

Load Balancers

High availability comes from running multiple instances of your application at the same time. A load balancer is a piece of equipment that will route traffic from your users to one of your instances that is live and well; it takes requests and sends them to the next healthy server.

The load balancer monitors the health of your virtual machines, and it can take different parameters into account. It can detect if your virtual machine or app crashes, but it can also check for network latency, specific data in the request headers and so much more.

Questions Your Clients Are Likely To Ask

So your application is running great, but your client is thinking about embracing the cloud. Are you ready for it? Here are common questions you should be able to answer to sound like a cloud expert.

When Do I Want More Than A Hosting Provider?

Your client might be engaged full speed ahead on migrating all services to the cloud. With greater flexibility, resiliency and a geographically distributed presence, the cloud makes it easy to get excited.

But even though the cloud is faster and more flexible and dependable, it’s also costlier; it might even require additional IT support to keep your client’s system running. The cloud is not for everyone.

If your client’s system is currently running on a hosting provider, should you move to the cloud?

Consider present and future needs: If your client is looking for high availability to comply with regulations, then move to the cloud. If your client is targeting a global audience, move to the cloud. If drastic surges in demand throughout the year are expected, move to the cloud.

If the system will be mostly accessed by local users within a specific geography, or if it’s not mission-critical to your client, then don’t move to the cloud.

The important takeaway: If your client’s system runs well on a hosting provider, you should consider existing SaaS offerings that would provide the resilience and performance of the cloud, while isolating your client from unnecessary IT expenses. There are traditional hosting providers like Bluehost offering cloud-based services, and there are cloud providers offering hosting services.

What Type Of Cloud Should I Use?

Finding the right type of cloud can be overwhelming, with each provider offering a wide range of services and options. The first things to consider are the complexity of your client’s software stack and the hardware it’s currently running on.

If the whole stack is highly customized with recompiled open-source libraries, customized Linux kernels or special storage optimizations, you should look at IaaS first. Some providers will allow your client to mix and match, using IaaS for highly customized components while picking PaaS for other parts.

However, if your client’s needs are mostly built on top of off-the-shelf libraries, PaaS is most likely a better starting point; the cloud provider will make sure your client’s code will always be running on top of up-to-date dependencies.

Once the right cloud model is identified, the requirements and evaluation criteria will be unique to your client. But it’s always worth paying attention to non-functional requirements: Does your client have to comply with domain-specific regulations, certifications or standards? Do they have any dependency on or partnership with specific vendors?

Finally, think about the cloud provider’s migration support, and vendor lock-in — how hard it is for your customer to migrate to a competitor once the system is running. Consider an exit plan even if your client is not planning to move out.

How Do I Make Sure My Site Never Goes Down?

Let’s say your client is working in the U.S. healthcare industry. HIPAA requires that every organization has some sort of disaster recovery plan, and that includes your website. Your client’s business will fail if the site goes down, so you need the resiliency of the cloud.

The cloud gives you the tools you need to ensure that your site never goes down. You’ll need multiple instances of your application running at the same time, and a way to control traffic so your users will never access a bad instance.

If your client is deploying your site on an IaaS cloud, you’ll need multiple instances of your application and a load balancer to control traffic. If your client has a PaaS cloud, just ensure that you have multiple instances running, as the cloud will provide the routing part automatically.

If your site uses a database, make sure that your client’s cloud is configured to support session affinity (also called sticky sessions), a way to ensure that all user traffic is routed to the same virtual machine.

How Do I Make My Site Fast For Everyone In The World?

If your client is going global and requires your application to provide fast service to end users around the world, then you need the flexibility and geographic reach of the cloud.

Even though the cloud is global, you need instances of your application to be running close to where your users are.

Work with your client to identify which cloud regions would best serve your user base, and where your client is hosting the APIs that support your site — your instances should be close to both. You might also discuss setting up a global proxy that routes traffic to different geographical areas based on the user’s location.

Conclusion

Providing scalable and resilient service to a growing customer base across the Internet is very complex; we’ve barely scratched the surface here. That’s why we want to leave the details to Amazon, Google, and the other cloud providers. Your job is to make good decisions about how to use their services.

Remember, when your client asks you if something should run in the cloud, you need to ask four questions:

- How complex is the software you need to run?

- How much does it need to scale?

- How important is it that it never goes down?

- How fast does it need to run for users around the world?

Start with those four simple questions, and you’ll sound like a cloud expert. Work with your clients to understand what the answers to these questions mean for them, considering the different types of cloud, and you’ll be a big part of solving their needs.

Further Reading

- Why Content Is Such A Fundamental Part Of The Web Design Process

- A Guide To Attracting Clients To Your Agency

- The Feature Trap: Why Feature Centricity Is Harming Your Product

- Crafting Experiences: Uniting Rikyu’s Wisdom With Brand Experience Principles

Agent Ready is the new Headless

Agent Ready is the new Headless

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App