How To Create A Headless WordPress Site On The JAMstack

This article has been kindly supported by our dear friends at Netlify, an all-in-one platform for automating modern web projects. Thank you!

In the first article of this series, we walked through Smashing Magazine’s journey from WordPress to the JAMstack. We covered the reasons for the change, the benefits that came with it, and hurdles that were encountered along the way.

Like any large engineering project, the team came out the other end knowing more about the spectrum of successes and failures within the project. In this post, we’ll set up a demo site and tutorial for what our current recommendations would be for a WordPress project at scale: retaining a WordPress dashboard for rich content editing, while migrating the Front End Architecture to the JAMstack to benefit from better security, performance, and reliability.

We’ll do this by setting up a Vue application with Nuxt, and use WordPress in a headless manner — pulling in the posts from our application via the WordPress API. The demo is here, and the open-source repo is here.

If you wish to skip all the steps below, we’ve prepared a template for you. You can hit the deploy button below and modify it to your needs.

What follows is a comprehensive tutorial of how we set this all up. Let’s dig in!

Enter The WordPress REST API

One of the most interesting features of WordPress is that it includes an API right out of the box. It’s been around since late 2016 when it shipped in WordPress 4.7 and with it came opportunities to use WordPress new ways. What sort of ways? Well, the one we’re most interested in covering today is how it allows for the separation of the WordPress content and the Front End. Where building a WordPress theme in PHP was once the only way to develop an interface for a WordPress-powered site, the REST API ushered in a new era where the content management powers of WordPress could be extended for use outside the root WordPress directory on a server — whether that be an app, a hand-coded site, or even different platforms altogether. We’re no longer tethered to PHP.

This model of development is called a Headless CMS. It’s worth mentioning that Drupal and most other popular content management systems out there also offer a headless model, so a lot of what we show in this article isn’t just specific to WordPress.

In other words, WordPress is used purely for its content management interface (the WordPress admin) and the data entered into it is syndicated anywhere that requests the data via the API. It means your same old site content can now be developed as a static site, progressive web app, or any other way while continuing the use of WordPress as the engine for creating content.

Getting Started

Let’s make a few assumptions before we dive right in:

- WordPress is already up and running. Going over a WordPress install is outside what we want to look at in this article and it’s already well documented.

- We have content to work with. The site would be nothing without feeding it some data from the WordPress REST API.

- The front-end is developed in Vue.

We could use any number of other things, like React, Jekyll, Hugo, or whatever. We just happen to really like Vue and, truth be told, it’s likely the direction the Smashing Magazine project would have gone if they could start the process again. - We’re using Netlify. It was the platform Smashing migrated to, and is straightforward to work with. Full disclosure, Sarah works there. She also works there because she loves their service. :)

Setting Up Vue With Nuxt

Like WordPress, there’s already stellar documentation for setting up a Vue project, and Sarah has a Frontend Masters course (all the materials are free and open source on her GitHub). No need to rehash that here.

But what we’re actually going to do is create our app using NuxtJS. It adds a bunch of features to a typical Vue project (e.g. bundling, hot reloading, server-side rendering, and routing to name a few) that we’d otherwise have to piece together. In other words, it gives us a nice head start.

Again, setting up a NuxtJS project is super well documented, so still no need to get into that in this post. What is worth getting into is the project directory itself. It’d be nice to know what we’re getting into and where the API needs to go.

We’ll create the project with this command:

npx create-nuxt-app <project-name>

Here’s the general structure for a standard Nuxt project, leaving out some files for brevity:

[root-directory]

├── .nuxt

├── assets

├── components

├── AppNavigation.vue //any components you will reuse

└── AppFooter.vue

├── dist

├── layouts

└── default.vue //this gives you a standard layout, you can make many if you like, such as blog.vue, etc. We typically put our navs and footers here

├── middleware

├── node_modules

├── pages

├── index.vue //any .vue components we put in here will automatically become routed pages!

└── about.vue

├── plugins

├── static

| └── index.html

├── store

└── index.js //we’ll put any state we need to share around the application in here, including the calls to the REST API to update the data. This is called a Vuex store. By creating the index page, Nuxt registers it.

└── nuxt.config.js

That’s about it for our Vue/Nuxt installation! We’ll create a component that fetches data from a WordPress site in just a bit, but this is basically what we’re working with.

Static Hosting

Before we hook the Vue app up with Netlify, let’s create a repository for the project. One of the benefits of a service like Netlify is that it can trigger a deploy when changes are pushed to the master (or some other) branch of a repository. We’ll definitely want that. Git is automatically initialized in a new Vue installation, so we get to skip that step. All we need to do is create a new repository on GitHub and push the local project to master. Anything in caps is something you will replace with your own information.

### Add files

git add .

## Add Remote Origin

git remote add origin git@github.com:USERNAME/REPONAME.git

## Push Everything To The Remote Repo

git push -u origin master

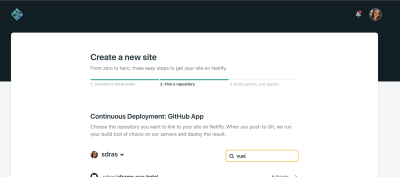

Now, we’re going to head over to our Netlify account and hook things up. First, let’s add a new site from the Sites screen. If this is your first time using Netlify, it will ask you to give it the authorization to read repositories from your GitHub (or GitLab, or BitBucket) account. Let’s select the repository we set up.

Netlify will confirm the branch we want to use for deployments. There’s also a spot to tell Netlify what we use for the build task that compiles our site for production and which directory to look at.

We’ll be prompted for our build command and directory. For Nuxt it’s:

- Build command:

yarn generateornpm run generate - Directory:

dist

Check out the full instructions for deploying a Vue app to Netlify for more details. Now we can deploy! 🎉

Setting Up The Store

No, we’re not getting into e-commerce or anything. Nuxt comes equipped with the ability to use a Vuex store out of the gate. This provides a central place where we can store data for components to call and consume. You can think of it like the “brains” of the application.

The /store directory is empty by default. Let’s create a file in there to start making a place where we can store data for the index page. Let’s creatively call that index.js. Sarah has a VS Code extension with shortcuts that make this setup fairly trivial. With that installed (assuming you’re using VS Code, of course) we can type vstore2 and it spits out everything we need:

export const state = () => ({

value: 'myvalue'

})

export const getters = {

getterValue: state => {

return state.value

}

}

export const mutations = {

updateValue: (state, payload) => {

state.value = payload

}

}

export const actions = {

updateActionValue({ commit }) {

commit('updateValue', payload)

}

}

Basically, the setup is as follows:

stateholds the posts, or whatever info we need to store.mutationswill hold functions that will update the state. Mutations are the only thing that can updatestateactions cannot.actionscan make asynchronous API calls. We’ll use this to make the call to WordPress API and then commit a mutation to update the state. First, we’ll check if there’s any length to the posts array instate, which means we already called the API, so we don’t do it again.

Right off, we can nix the getters block because we won’t be using those right now. Next, we can replace the value: ‘myValue’ in the state with an empty array that will be reserved for our posts data:posts: []. This is where we’re going to hold all of our data! This way, any component that needs the data has a place to grab it.

The only way we can update the state is with mutations, so that’s where we’re headed next. Thanks to the snippet, all we need to do is update the generic names in the block with something more specific to our state. So, instead of updateValue, let’s go with updatePosts; and instead of state.value, let’s do state.posts. What this mutation is doing is taking a payload of data and changing the state to use that payload.

Now let’s look at the actions block. Actions are how we’re able to work with data asynchronously. Asynchronous calls are how we’ll fetch data from the WordPress API. Let’s update the boilerplate values with our own:

/*

this is where we will eventually hold the data for all of our posts

*/

export const state = () => ({

posts: []

})

/*

this will update the state with the posts

*/

export const mutations = {

updatePosts: (state, posts) => {

state.posts = posts

}

}

/*

actions is where we will make an API call that gathers the posts,

and then commits the mutation to update it

*/

export const actions = {

//this will be asynchronous

async getPosts({

state,

commit

}) {

//the first thing we’ll do is check if there’s any length to the posts array in state, which means we already called the API, so don’t do it again.

if (state.posts.length) return

}

}

If that errors along the way, we’ll catch those errors and log them to the console. In production apps, we would also check if the environment was development before logging to the console.

Next, in that action we set up we’re going to try to get the posts from the API:

export const actions = {

async getPosts({ state, commit }) {

if (state.posts.length) return

try {

let posts = await fetch( `https://css-tricks.com/wp-json/wp/v2/posts?page=1&per_page=20&_embed=1`

).then(res => res.json())

posts = posts

.filter(el => el.status === "publish")

.map(({ id, slug, title, excerpt, date, tags, content }) => ({

id

slug,

title,

excerpt,

date,

tags,

content

}))

commit("updatePosts", posts)

} catch (err) {

console.log(err)

}

}You might have noticed we don’t just take all of the information and store it, we’re filtering out only what we need. We do this because WordPress does indeed store a good deal of data for each and every post, only some of which might be needed for our purposes. If you’re familiar with REST APIs, then you might already know that they typically return everything. For more information about this, you can check out a great post by Sebastian Scholl on the topic.

That’s where the .filter() method comes in. We can use it to fetch just the schema we need which is a good performance boost. If we head back to our store, we can filter the data in posts and use .map() to create a new array of that data.

Let’s do this so that we only get published posts (because we don’t want drafts showing up in our feed), the Post ID (for distinguishing between posts), the post slug (good for linking up posts), the post title (yeah, kinda important), and the post excerpt (for a little preview of the content), and some other things like tags. We can drop this in the try block right before the commit is made.

This will give us data that looks like this:

posts: [

{

content:Object

protected:false

rendered:"<p>Fluid typography is the idea ..."

date:"2019-11-29T08:11:40"

excerpt:Object

protected:false

rendered:"<p>Fluid typography is the idea ..."

id:299523

slug:"simplified-fluid-typography"

tags:Array[1]

0:963

title:Object

rendered:"Simplified Fluid Typography"

},

…

]

OK, so we’ve created a bunch of functions but now they need to be called somewhere in order to render the data. Let’s head back into our index.vue file in the /pages directory to do that. We can make the call in a script block just below our template markup.

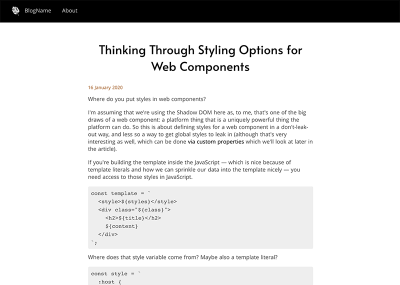

Let’s Render Them!

In this case, we want to create a template that renders a loop of blog posts. You know, the sort of page that shows the latest 10 or so posts. We already have the file we need, which is the index.vue file in the /pages directory. This is the file that Nuxt recognizes as the “homepage” of the app. We could just as easily create a new file if we wanted the feed of posts somewhere else, but we’re using this since we’re dealing with a site that’s based around a blog. Let’s open that file, clear out what’s already there and drop our own template markup in there.

We’ll dispatch this action, and render the posts:

<template>

<div class="posts">

<main>

<h2>Posts</h2>

<!-- here we loop through the posts -->

<div class="post" v-for="post in posts" :key="post.id">

<h3>

<!-- for each one of them, we’ll render their title, and link off to their individual page -->

<a :href="`blog/${post.slug}`">{{ post.title.rendered }}</a>

</h3>

<div v-html="post.excerpt.rendered"></div>

<a :href="`blog/${post.slug}`" class="readmore">Read more ⟶</a>

</div>

</main>

</div>

</template>

<script>

export default {

computed: {

posts() {

return this.$store.state.posts;

},

},

created() {

this.$store.dispatch("getPosts");

},

};

</script>

In the created lifecycle method, you see we’re kicking off that action that will fetch the posts from the API. Then we’ll store those posts we get in a computed property called posts. Then in the template, we loop through all the posts, and render the title and the excerpt from each one, linking off to an individual post page for the whole post (think like single.php) that we haven’t built yet. So let’s do that part now!

Creating Individual Post Pages Dynamically

Nuxt has a great way of creating dynamic pages, with minimal code, you can set up a template for all of your individual posts.

First, we need to create a directory, and in there, put a page with an underscore, based on how you will render it. In our case, it will be called blog, and we’ll use the slug data we brought in from the API, with an underscore. Our directory will then look like this:

index.vue

blog/

_slug.vue

<script>

export default {

computed: {

posts() {

return this.$store.state.posts;

}

},

created() {

this.$store.dispatch("getPosts");

}

};

</script>

We’ll dispatch the getPosts request, just in case they enter the site via one of the individual pages. We’ll also pull in the posts data from the store.

We also have to make sure this page knows which post we’re referring to. The way we’ll do this is to store this particular slug with this.$route.params.slug. Then we can find the particular post and store it as a computed property using filter:

computed: {

...

post() {

return this.posts.find(el => el.slug === this.slug);

}

},

data() {

return {

slug: this.$route.params.slug

};

},

Now that we have access to the particular post, in the template, we’ll render the title, and also the content. Due to the fact that the content is a string that has HTML elements already included that we want to use, we’ll use the vue directive v-html to render that output.

<template>

<main class="post individual">

<h1>{{ post.title.rendered }}</h1>

<section v-html="post.content.rendered"></section>

</main>

</template>

The last thing we have to do is let Nuxt know that it needs to generate all of these dynamic routes. In our nuxt.config.js file, we’ll let nuxt know when we use the generate command (which allows nuxt to build statically), to use a function to create the routes. We’ll call our function dynamicRoutes.

generate: {

routes: dynamicRoutes

},

Next, we’ll install axios by running yarn add axios at the top of the file we’ll import it. Then we’ll create a function that will generate an array of posts based on the slugs we retrieve from the API. I cover this in more detail in this post.

import axios from "axios"

let dynamicRoutes = () => {

return axios

.get("https://css-tricks.com/wp-json/wp/v2/posts?page=1&per_page=20")

.then(res => {

return res.data.map(post => `/blog/${post.slug}`)

})

}

This will create an array that looks something like this:

export default {

generate: {

routes: [

'/blog/post-title-one',

'/blog/post-title-two',

'/blog/post-title-three'

]

}

}

And we’re off to the races! Now let’s deploy it and see what we’ve got.

Create The Ability To Select Via Tags

The last thing we’re going to do is select posts by tag. It works very similarly for categories, and you can create all sorts of functionality based on your data in WordPress, we’re merely showing one possible path here. It’s worth exploring the API reference to see all that’s available to you.

It used to be that when you gathered the tags data from the posts, it would tell you the names of the tags. Unfortunately, in v2 of the API, it just gives you the id, so you have to then make another API call to get the actual names.

The first thing we’ll do is create another server-rendered plugin to gather the tags just as we did with the posts. This way, it will do this all at build time and be rendered for the end-user immediately (yay JAMstack!)

export default async ({ store }) => {

await store.dispatch("getTags")

}

Next, we’ll create a getTags action, where we pass in the posts. The API call will look very similar, but we have to pass in the tags in this format, where after include UTM we pass in the IDs, comma-separated, like this:

https://css-tricks.com/wp-json/wp/v2/tags?include=1,2,3

In order to format it like that, we’ll have to take the posts and extract all the ids. We’ll do so with a .reduce() method:

async getTags({ state, commit }, posts) {

if (state.tags.length) return

let allTags = posts.reduce((acc, item) => {

return acc.concat(item.tags);

}, [])

allTags = allTags.join()

try {

let tags = await fetch(

`https://css-tricks.com/wp-json/wp/v2/tags?page=1&per_page=40&include=${allTags}`

).then(res => res.json())

tags = tags.map(({ id, name }) => ({

id, name

}))

commit("updateTags", tags)

} catch (err) {

console.log(err)

}

}

Just like the posts, we’ll need a place in state to store the tags, and a mutation to update them:

export const state = () => ({

posts: [],

tags: []

})

export const mutations = {

updatePosts: (state, posts) => {

state.posts = posts

},

updateTags: (state, tags) => {

state.tags = tags

}

}

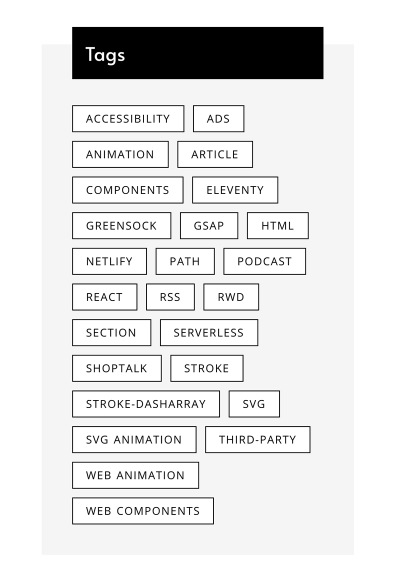

Now, in our index.vue page, we can bring in the tags from the store and display all of them

computed: {

tags() {

return this.$store.state.tags;

},

}

<aside>

<h2>Categories</h2>

<div class="tags-list">

<ul>

<li

v-for="tag in tags"

:key="tag.id">

<a>{{ tag.name }}</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

</aside>

This will give us this visual output:

Now, this is fine, but we might want to filter the posts based on which one we selected. Fortunately, computed properties in Vue make small work of this.

<template>

<div class="posts">

<aside>

<h2>Categories</h2>

<div class="tags-list">

<ul>

<li

@click="updateTag(tag)"

v-for="tag in tags"

:key="tag.id">

<a>{{ tag.name }}</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

</aside>

</div>

</template>

<script>

export default {

data() {

return {

selectedTag: null

}

},

methods: {

updateTag(tag) {

if (!this.selectedTag) {

this.selectedTag = tag.id

} else {

this.selectedTag = null

}

}

},

...

};

</script>

First, we’ll store a data property that allows us to store the selectedTag. We’ll start it off with a null value.

In the template, when we click on the tag, we’ll execute a method that will pass in which tag it is, named updateTag. We’ll use that to either set selectedTag to the tag ID or back to null, for when we’re done filtering.

From there, we’ll change our v-for directive that displays the post from"post in posts" to "post in sortedPosts". We’ll create a computed property called sortedPosts. If the selectedTag is set to null, we’ll just return all the posts, but otherwise we’ll return only the posts filtered by the selectedTag:

<template>

<main>

<h2>Posts</h2>

<div class="post" v-for="post in sortedPosts" :key="post.id">

</div>

</main>

</template>

<script>

computed: {

sortedPosts() {

if (!this.selectedTag) return this.posts

return this.posts.filter(el => el.tags.includes(this.selectedTag))

}

},

</script>

Now the last thing we want to do to polish off the application is style the selected tag just a little differently, and let the user know you can deselect it.

<template>

<div class="posts">

<aside>

<h2>Categories</h2>

<div class="tags-list">

<ul>

<li

@click="updateTag(tag)"

v-for="tag in tags"

:key="tag.id"

:class="[tag.id === selectedTag ? activeClass : '']">

<a>{{ tag.name }}</a>

<span v-if="tag.id === selectedTag">✕</span>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

</aside>

</div>

</template>

<script>

export default {

data() {

return {

selectedTag: null,

activeClass: 'active'

}

},

</script>

And there you have it! All the benefits of a rich content editing system like WordPress, with the performance and security benefits of JAMstack. Now you can decouple the content creation from your development stack and use a modern JavaScript framework and the rich ecosystem in your own app!

Once again, if you wish to skip all these steps and deploy the template directly, modifying it to your needs, we set this up for you. You can always refer back here if you need to understand how it’s built.

There are a couple of things we didn’t cover that are out of the scope of the article (it’s already quite long!)

Further Reading

- Exploring Enhanced Patterns In WordPress 6.3

- Building Future-Proof High-Performance Websites With Astro Islands And Headless CMS

- Building The SSG I’ve Always Wanted: An 11ty, Vite And JAM Sandwich

- Context And Variables In The Hugo Static Site Generator